It was 11 minutes past 2 a.m. when the order to stand up was given inside the C-141 Starlifter cruising over Panamanian airspace.

The “cherry” paratrooper next to then-Maj. Paul D. Schambach was struggling to comply — likely due to the mortar base-plate and three rounds he was hauling.

“He was a stout young man, but I still had to help him,” said Schambach, an intelligence officer with the 82nd Airborne Division’s ready brigade during the 1989 mission.

Normally, a freshly christened paratrooper’s first jump out of Airborne School is in training at about 1,000 feet above ground, allowing for plenty of time to pull a reserve parachute should anything go amiss. But Schambach recalled that the young soldier on his “cherry jump” next to him wasn’t so lucky. This combat jump was going to be dangerously low to reduce the exposure to enemy fire.

“All of our reserves were loose-rigged. You don’t have but a nano-second to pull a reserve at 500 feet," he said. "And we think it was probably low enough that it wouldn’t have worked anyhow.”

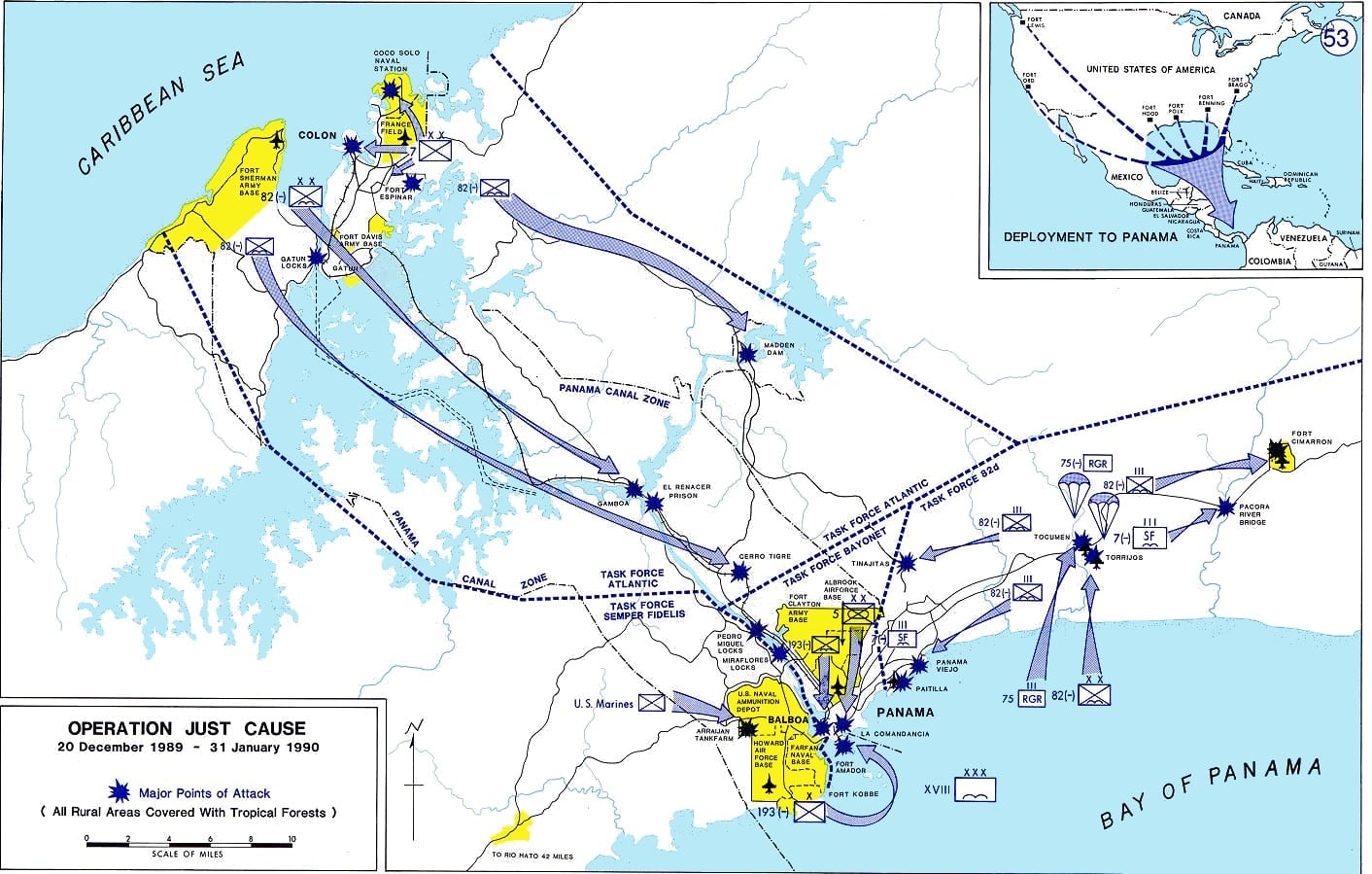

Schambach helped plan the 82nd’s assault onto Torrijos International Airfield in the early morning hours of Dec. 20, 1989. The goal of the invasion was to capture Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega, a former ally of the United States who fell out of favor in the 1980s and whose capture still stands as a controversial execution of U.S. military action today.

But at the strategic and tactical level, the operation was fairly straightforward. The 82nd was tasked to follow the 75th Ranger Regiment onto Torrijos, east of Panama City, eliminate the threats, block reinforcements and set up a command post before moving to assault other targets. In addition to being an international airport, Torrijos garrisoned the Panamanian Army’s 2nd Infantry Company and the headquarters for the Panamanian Air Force.

“The Panamanian plan was to melt into the jungle and then conduct guerrilla-type operations” in the event of a U.S. invasion, said John W. Aarsen, director of the 82nd Airborne Division War Memorial Museum at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. “But a lot of the units ended up staying in place and they actually fought pretty hard. And that’s because their NCOs were well-trained and held their units together.”

WARNO at the Christmas party

Contingency plans for the invasion of Panama were already well underway when Lt. Col. Rick Allenbaugh, who would serve as the division G2, arrived at the unit in the summer of 1989.

Map drills and rehearsals preceded a full-blown readiness exercise in the fall that covered Fort Bragg and the surrounding areas, Allenbaugh recalled.

“We had been fortunate enough over the summer to do a series of map exercises on-site in Panama with SOUTHCOM,” Allenbaugh said. “The [commanding general] would arrange aircraft, they’d come in at night, we’d fly down there, always move around at night, do our rehearsal and then fly back at night.”

By December, though, tensions in Panama had reached a fever pitch, as Noriega declared himself the “maximum leader” and speculated that someday the “bodies of our enemies” would float down the Panama Canal.

Noriega had been indicted on drug-trafficking charges in U.S. courts the previous year, but it was impossible to get him stateside to face trial. The Panamanian leader who had long been a Cold War ally of the C.I.A — and whose drug-related activities were previously condoned, or at the very least ignored — was beginning to court new allies that included Cuba and the still-standing Soviet Union, the Joint Chiefs of Staff feared.

Panama was of great strategic importance to the United States. Thousands of service members were stationed near the Panama Canal to safeguard the waterway that bridged the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and sped the transit of naval and merchant marine vessels. But after an attempted coup and deteriorating relations with the U.S. government, long-term access to the canal was in jeopardy and security forces were increasingly harassing U.S. citizens in the country.

At a Dec. 16, 1989, Christmas party with other Army officers, Allenbaugh remembered hearing the news that a young U.S. Marine, 1st Lt. Robert Paz, was killed during a Saturday night outing. The car he was in had taken a wrong turn and wound up being sprayed with gunfire at a Panamanian checkpoint. Paz died after being taken to a local hospital.

“We got in a little huddle and figured that was going to be the trigger. And sure enough, the next morning we got the warning order,” Allenbaugh said.

Loading at Green Ramp

Schambach, the 82nd intelligence officer, and other soldiers who would jump into Panama were sequestered from landlines and families on Pope Air Force Base, essentially an annex to Fort Bragg.

Ammunition, rations and maps were distributed as the paratroopers conducted battle planning and ate their last hot meal before the jump.

“I remember I got a shot there that made sitting down on the airplane very, very painful,” Schambach said. “I don’t know what it was for, but I know that we all had to bend over and take one.”

Paratroopers in light-weight battle fatigues and T-shirts rehearsed over terrain maps and other visual aids down to the team leader level as rain came down outside and ice formed on the C-141 strategic airlift planes that would ferry the soldiers to Central America.

As the aircraft were de-iced, the paratroopers loaded for a five-hour flight.

“Every paratrooper, for every jump they’ve had, they’ve also had a flight cancellation,” Schambach noted. “Once you get aboard the airplane, you don’t know if it’s going to be a no-go."

The lead plane to Panama had a tactical satellite radio for intelligence updates. While in-flight, the roughly 2,000 paratroopers inside the 40-plane armada received indications that Panamanian forces were warned of the invasion.

Back in 1989, intelligence was primarily concerned that Cuba would notice the large fleet of aircraft and warn Panama. But today, Schambach pondered how operational security at that level could possibly be maintained.

“There’s a website today that can track aircraft all over the United States and all over the world,” he said. “Some people do that as a hobby and I wonder how they would mask that today.”

Regardless, the mission wasn’t aborted en-route and the paratroopers arrived over the objective at about 2 a.m. on Dec. 20, 1989.

‘Pucker factor is high’

Allenbaugh had well over 100 static-line parachute jumps on his resume by the time he arrived over the drop zone.

“Every jump, it doesn’t matter how many you’ve done, I’d say the pucker factor is high,” Allenbaugh said. “But it’s a great feeling when you exit that door.”

The aircraft had offset their run-in heading to the airfield, meaning the paratroopers were dumped in 10-foot grass and swampland off to the side of the runway. That might have been done to keep the runway clear of parachutes so airlift operations could quickly commence, but it could also have been because tracers were coming through the airport as Rangers assaulted through the terminals, according to Schambach.

“I do recall seeing tracers coming across the runway as the airplanes were approaching at 500 feet,” he added. “I think they were veering slightly to the right, away from the terminal.”

The paratroopers found themselves on the outside of a 12-foot fence guarding the runway. Schambach, who stands at 6 feet, had to shot-put his 60-pound rucksack over the obstacle before he could climb to the other side, which took several attempts.

“Once I got on the other side, a young soldier came up on the side I just came over and said ‘I have one of those new bayonets, can I cut the fence?’ and I said: ‘Yeah! cut the fence!’” Schambach recalled. “He had a much easier time than me.”

After the paratroopers made it past the fence, they began meeting at assembly areas on the runway to start follow-on operations. A command post was established inside a large garage found on the airfield and the paratroopers strung up maps and line-of-sight communications nets.

Schambach’s job was to help collate information on the objective, taking intelligence reports and plotting enemy positions. One of the first such report he heard that night was of enemy mechanized troops approaching the airfield. They were quickly dispatched by an AC-130 gunship circling overhead.

“That first 24-hour period, it progressed much faster than we thought,” he said, adding that an ice storm that delayed their arrival may have been helpful to that end. “We came over the drop zone in increments of four or five planes at a time and it was extended out over several hours. ... It must have looked to the Panamanians like the airdrops were never going to stop.”

Shutting down Radio Nacional

Rick Lamb, a retired Army Green Beret command sergeant major, was already stationed in Panama with Charlie Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group, as the invasion unfolded. He was assigned to Fort Sherman, which housed the jungle warfare school and guarded the northern end of the Panama Canal.

Lamb’s team was originally tasked with securing elected officials who the U.S. government said were the true winners of the May 1989 presidential election in Panama. But the night before the invasion, the officials were invited to dinner at the American embassy, told about the operation and put under protection.

So they went to their alternate mission: take down the lines of communication. The first target was Radio Nacional.

“We were in the Hanger at Albrook Air Force Base, waiting on a mission, and there was a transistor radio playing,” Lamb said. “Noriega was speaking on the radio telling people to grab kitchens knives and to continue to fight.”

One of the Green Berets went to the phone book and pulled the address for Radio Nacional, which was housed in the large Contraloria building “just down the street,” Lamb recalled. The team ran some tape drills to rehearse the insertion and spun up the helicopters.

“We fast-roped onto the compound for Radio Nacional, I think it was like an 18-story building,” he said. “We were going to blow the antenna off the roof, but in the event that Noriega was inside, we wanted to take him prisoner.”

After the team fast-roped down, the ropes were dropped onto the roof, which proved useful. The Green Berets didn’t have enough charges to both take down the antenna and blow open the door to the lower levels. Instead, they looped the fast rope around an air conditioning unit on the roof and threw it over the side of the building to a balcony below.

“Then we slid over the side of the building down onto the balcony ... and we breached the sliding glass doors to get access to the office and ran upstairs to let the other boys in," Lamb said. “Then we ran down to the radio station some floors down and it wasn’t occupied. It was just a tape."

The team took fire coming out of the building that housed Radio Nacional.

“Trying to get from the building to our evacuation HLZ, we were constantly under fire, but there were no targets to return fire without taking civilians,” Lamb recalled.

Refuge at the Holy See

Special operations forces pursued targets and the 82nd cleared Torrijos International Airfield and established a command-and-control node as the search for Noriega commenced.

The paratroopers took casualties after they moved out from the drop zone to assault Panamanian military outposts in the vicinity of the airfield, according to Aarsen. Six of 23 American service members killed in action during the invasion were serving under the 82nd.

Once the paratroopers reached their assault objectives, the Panamanian forces quickly capitulated, according to an intelligence insights document written after the operation. Within 48 hours of the parachute assault, all major garrisons within the Panama City-area had been seized, the document noted.

Lamb recalled his Spanish-speaking Green Beret team helping to negotiate the surrender of Panamanian soldiers at Rio Hato, 50 miles from the canal zone. During the surrender, a large contingent of Rangers were “positioned out in the shadows.”

“The only guys that they saw were the 12 on the [Special Forces team],” Lamb said. That’s when a few Panamanians began discussing shooting the Green Berets rather than surrender to such a small American force.

“So we asked the AC-130 gunship hovering over the top to light the area up with a big searchlight,” Lamb added. “And they were able to see and went: ‘Oh, my God, we’re surrounded.’”

The sheer size and quickness of the assault force prevented Panamanian military leaders from having the time to melt into the jungle and begin a protracted guerrilla war as they supposedly planned.

“We believe once the PDF leadership realized the size of the assault force, they simply changed clothes and went home or into hiding leaving their junior men to fend for themselves,” the intelligence insight document reads.

Rumors and human intelligence reports abounded during this time. One such rumor was that Noriega had been at the airfield in the hours prior to the invasion, according to Allenbaugh, the division G2.

“It turned into a major HUMINT operation, as we anticipated,” Allenbaugh said. “We embedded a Spanish-speaking soldier, it didn’t matter where they came from, with each squad as they moved through the areas.”

The command post kept track of people who had been interrogated and set up a phone bank to take tips from local Panamanians. After the tip was determined to be valid enough to react, soldiers would be tasked to investigate. The paratroopers would color-code a map of Panama City as it was gradually swept through and deemed “friendly" until Noriega was ultimately cornered.

Over the first few days of the invasion, Noriega used tactics like broadcasting recordings of his voice to avoid the Americans. By the fifth day, he managed to make his way to the Holy See’s embassy in Panama and sought asylum. He would remain there until Jan. 3, 1990, when he surrendered to U.S. troops.

Noriega spent the rest of his life being shuttled through courts and prisons in the United States, France and Panama on various charges of drug-related activity, money laundering and crimes committed during his rule.

The operation was in large part a success for the U.S. military, as it stood as a testament to the joint planning and execution developed between the armed services following shortcomings noticed during the Grenada invasion in 1983.

For the 82nd, the Panama invasion was the first combat jump since World War II and the largest combat jump since Operation Market Garden. Originally, the plan called for bringing the 7th Infantry Division down by air-landing them all in one night or incrementally under the guise of a training exercise. But both ideas were deemed too difficult to pull off, Aarsen, the 82nd historian, said

In the end, the 82nd was chosen to conduct a parachute assault because it was the quickest way to mass troops in the country.

“I think Panama is a good example of what joint forcible entry can do,” Aarsen added. “And that’s the same thing we think will happen in the future. An enemy won’t give us time to land 100,000 to 200,000 soldiers on a continent somewhere, and build up, then attack."

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.