Day after day, the planes took off. Sometimes one minute apart, the shiny new “Superfortresses” humming through the sky over the vast Pacific to strike at the heart of the enemy and end World War II.

Maj. Jack Koser took to the skies on those never-ending flights. So did 1st Lts. Ed Vincent and Warren Higgins. Fresh-faced they flew. Some, teenagers barely out of high school. Now one has passed the century mark and others are not far behind.

Their planes had painted pictures and names like “Flak Alley Sally” and “Lucky Strike” and “Here’s Lucky.”

They hit the Japanese homeland hard. Fires raged. Mines they dropped dotted the harbors and bays, stalling supplies and choking the country’s navy.

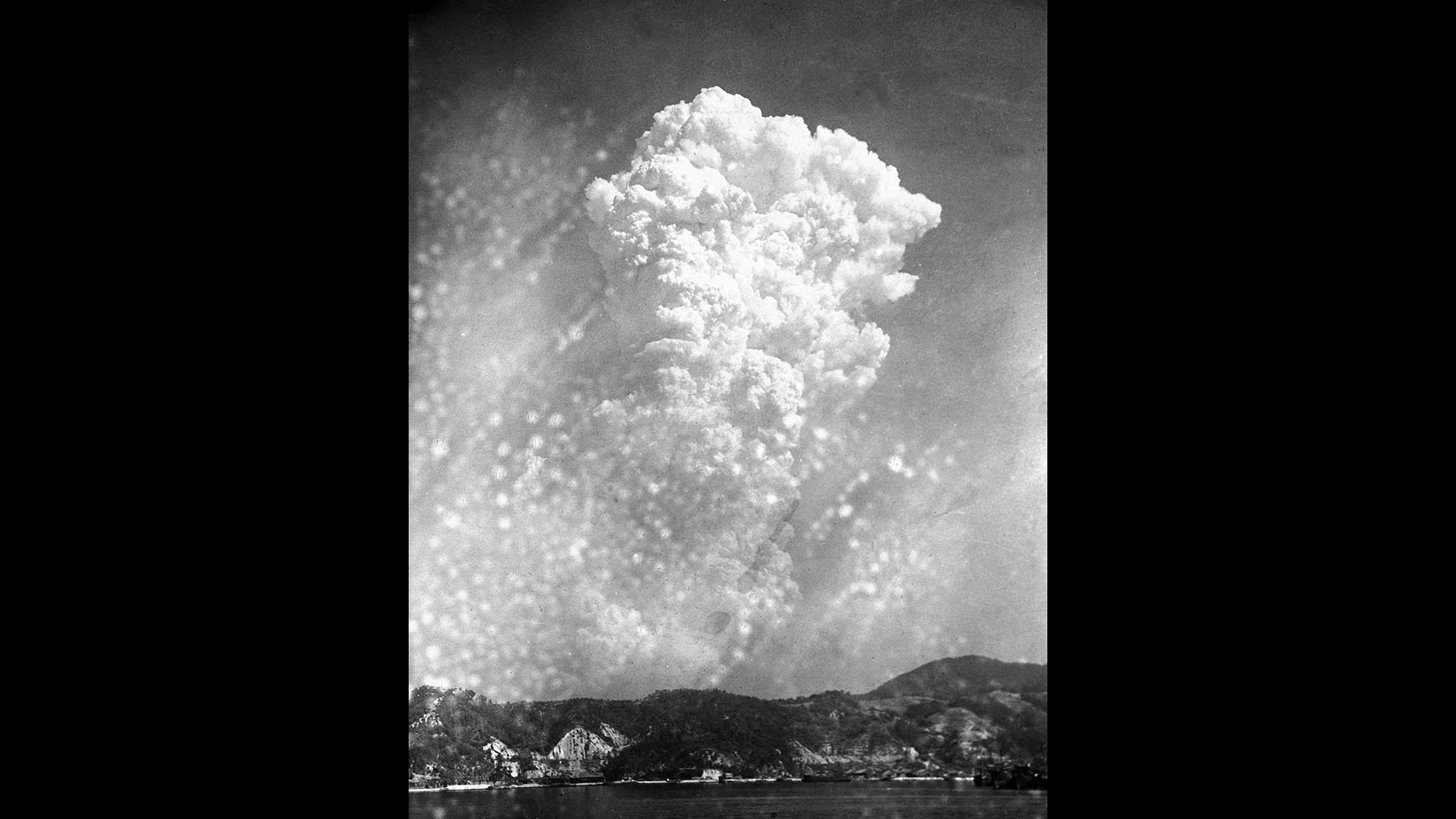

Today, Aug. 6, marks the 75th anniversary of the day that the United States dropped the first atomic bomb, hitting Hiroshima, Japan, and three days later another bomb for Nagasaki.

Those historic, cataclysmic events sped up the end of the war and set the stage for the nuclear arms race and subsequent Cold War. The single bomb dropped this day in 1945 killed an estimated 140,000 people from both the blast and aftereffects.

But those monumental events have overshadowed harrowing, death-defying and incredible work done by soldiers, sailors and Marines who took blood-soaked islands in the Pacific in the long slog toward Tokyo. And the air and ground crews flying off that hard-won soil to finally reach the heart of the enemy that dared attack the United States at Pearl Harbor.

The plane that dropped the big one.

And there was another piece of military technological history that some argue had a larger hand in ending the war than it gets credit for — the B29 Superfortress.

Though Tinian was where the famed “Enola Gay” launched its fateful mission to deliver the first A-bomb, it was also home to the 6th Bomb Group, which served as cover for the super-secret mission.

The unit also hid the “Enola Gay” for a time, before it loaded its infamous payload “Little Boy” the first Atomic Bomb dropped in war — on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945.

The 6th Bomb Group, part of the Army Air Corps’ 313th Bomb Wing, 20th Air Force, made it to Tinian, one of the last Pacific islands in a chain leading to mainland Japan, months after Allied forces took the island in a battle that lasted just a few days but claimed more than 5,000 Japanese forces and more than 300 U.S. Marines.

RELATED

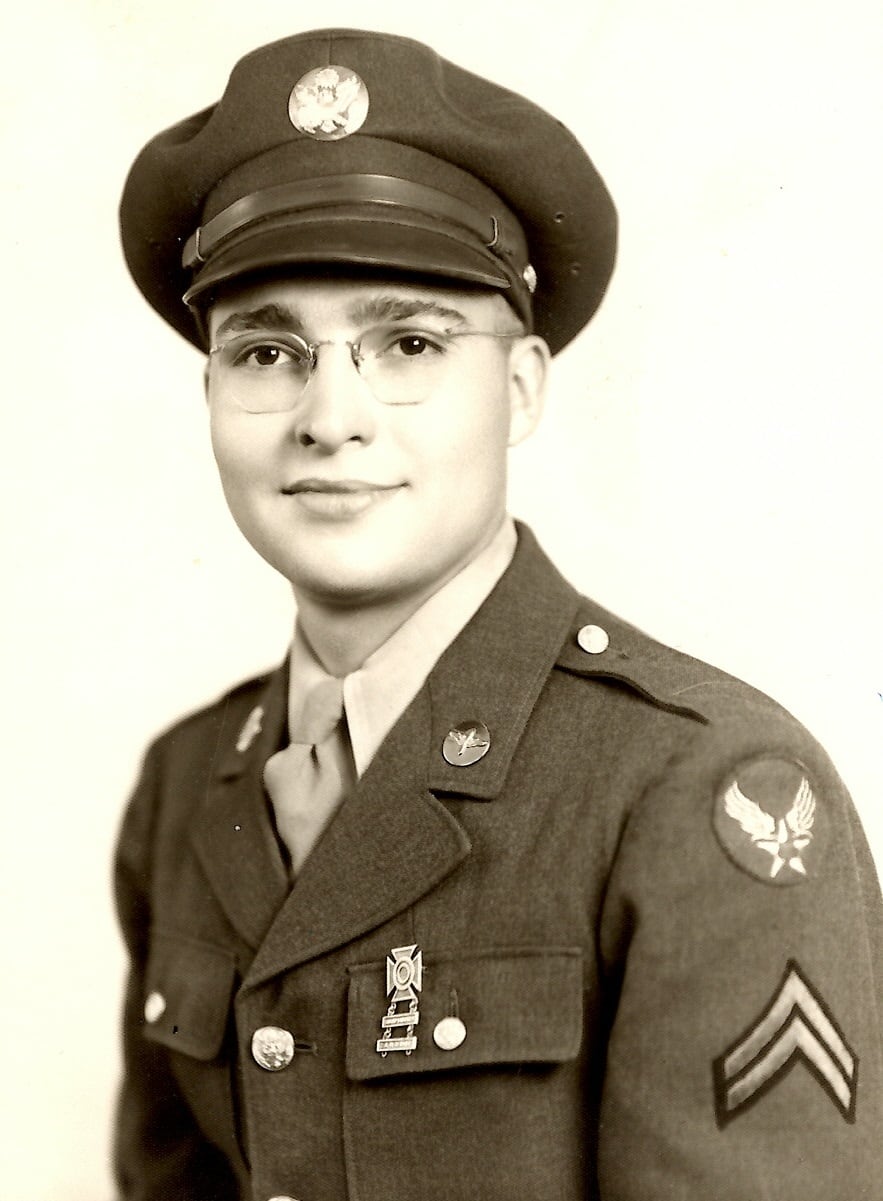

Koser, Vincent and Higgins served on different crews, but all had similar experiences. They’d signed up with the new Army Air Corps to fly. At first, they’d been trained on the B-17 “Flying Fortress,” which was helping win the war in Europe.

But that aircraft, as good as it was, couldn’t compare to the B-29. And the B-17 just couldn’t make the distances needed in this combat theater.

The older bomber could carry a crew of 10, flying up to 287 mph for a maximum range of about 2,000 miles. That might get a crew to Japan. It wouldn’t get them back.

The new B-29, however, carried an 11-person crew and could go 357 mph for a range of 3,250 mph.

The B-29 featured the first ever fully pressurized nose and cockpit in a bomber; an aft area for the crew was also pressurized, making it far more comfortable to fly.

And it could carry a lot more bombs.

Which is exactly what it did over Japan.

Though the first A-bomb changed warfare forever, the bombing runs on Tokyo, some experts argue, may have done as much or more to devastate the Japanese military’s will to fight. They claimed as many or more casualties and laid waste to as much territory in an even larger city.

Vincent, 97, was only 19 years old when he flew as a co-pilot on early missions out of Tinian to Japan. He remembers seeing flashes of light from Iwo Jima as Marines took the island to provide bombers a refueling and stopover on their missions to the mainland.

Though the tide had turned, ground troops and aircrews had no illusions that the Japanese military would simply surrender.

Despite months of sustained bombing and island after island falling, they continued to fight.

Retired Marine Maj. John Haynes, 90, was only 15 years old when he landed on Okinawa. He missed the taking of the island but was likely one of the bodies to be flung ashore on mainland Japan in the seemingly inevitable invasion.

Secret weapon

Unknown to the Tinian crews or the Marines slogging through the island campaign, a new weapon was on its way.

A few weeks before Aug. 6, 1945, Koser was leading flights over Tinian as they prepped for more missions when he noticed more planes than usual in the 6th Bomb Group formation.

Seemed funny, but he didn’t take much notice.

Higgins and Vincent heard rumors about this new group and noticed that they’d painted the same unit design on the tail of their planes, even though they weren’t part of the 6th.

They asked, but the new guys were kept off at a distance and didn’t really talk much with the other crews.

“When they first came, we wondered what in the world were those guys doing,” Vincent said. “They weren’t going on any missions. We were going on missions and getting shot at.”

But, as good soldiers do, these Air Corps members continued on the mission.

“I don’t think anybody talked about it, we were all scared,” Vincent said.

His plane alone, “Flak Alley Sally” tallied 141 bullet holes in it from the anti-aircraft fire his crew took over Japan.

They flew one mission that was 19 hours 40 minutes long, likely the longest in the history of the war and covered 4,400 miles to reach and mine a harbor in Korea that still had Japanese forces.

Maybe the biggest news of the war came to the soldiers on Tinian almost as an afterthought.

“We found out after they dropped it,” Higgins, 96, said. “We were there, on the same airfield. They took off from Tinian, but until they bombed, we didn’t know anything. We weren’t even allowed to talk about atoms, didn’t even know what they were.”

For Haynes and others like him, mopping up continued. He and other Marines were sent to China to accept the surrender of masses of Japanese troops after the surrender.

David Wilson, a co-historian of the 6th Group and son of one of its members, maintains a lifelong personal connection to it through his late father, Staff Sgt. Bernard Wilson.

Wilson said that his father was most proud of three things during the war — that he was on the longest bombing mission, that he flew over the USS Missouri as the Japanese high command surrendered, ending the war, and that he was on a mission to bomb the main railroad access that would have helped stall the Japanese should there have been a land invasion by the United States.

And it is that mission and the code words that never came to abort a strike on the Marifu Railroad Yards at Iwakuni, Japan, that emerged when memory failed his aging father.

“I could go to my dad and ask him ‘Daddy what did you have for breakfast yesterday?’” Wilson said. “He couldn’t remember.”

But if he asked him about a special code used on that last mission, the response was always there, even at the end of his life.

“Daddy, you also told me about that code …” Wilson would begin.

“Break, Utah, Utah, Utah, Break,” his father would respond.

Even though the bombings stopped soon after the atomic weapons were employed, other missions continued. Cpl. Wallace Gake, 94, served on a ground crew and arrived on the island right after the bomb. Many crews went home to leave the Army and start new lives. The rest of the unit was sent to the Philippines.

But planes still had to fly, deliver supplies, transport people. And Gake was there for months after, keeping planes running with other maintenance crews.

“A lot of times the ground crews get forgotten. We don’t drop any bombs and we don’t shoot enemy fighters,” he said.

But for him not much changed. A very noisy life, planes continued to buzz off the island day and night.

It was one of those post-combat missions that remain Koser’s lasting memory, 75 years later.

“One of the first things I remember is seeing the Great Wall of China,” he recounted.

Inside his plane, the bomb bays were chock full of food, medicine, even bicycles. All of that with one destination — POW camps that still held Allied prisoners who hadn’t yet been reached by ground forces in China.

He still remembers flying low, maybe 500 feet off the ground, opening the first bomb bay to drop parachute-rigged supplies. Then circling the camp to see cheering survivors before dropping the second load.

“It was a wonderful time,” Koser said.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.