The Colorado National Guard is investigating the disciplinary actions and potential reprisal by a senior officer after one of the state’s part-time soldiers filed a federal lawsuit against his entire chain-of-command, alleging that his superiors infringed upon his First Amendment right to participate in Black Lives Matter protests

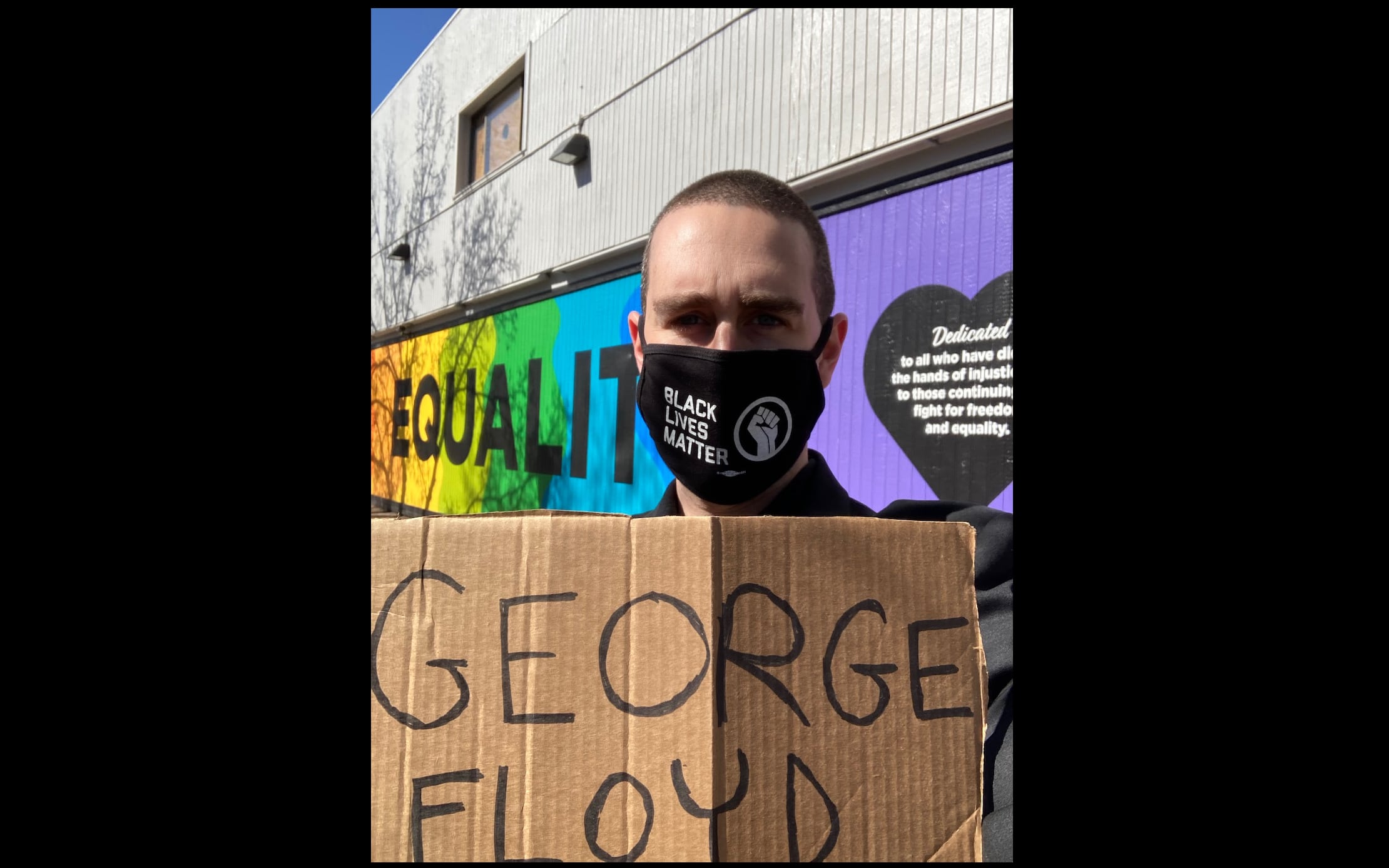

Army Capt. Alan Kennedy, a part-time Judge Advocate General Corps officer whose civilian work is in civil rights and constitutional law, faced repeated command investigations, reprimands, and other sanctions for writing op-eds in local newspapers and participating in Black Lives Matter protests while not in a duty status, according to the lawsuit he filed.

Generally speaking, Guard troops are only subject to active-duty speech restrictions when in uniform for their monthly drills or otherwise activated in a military capacity.

“There’s a double standard,” said Kennedy in a phone interview, pointing to other politically-active guardsmen like Florida state Rep. Anthony Sabatini, a firebrand conservative who is an officer in the Florida National Guard. “The Colorado National Guard’s investigated my participation in Black Lives Matter protests and op-eds while not investigating the op-eds of another judge advocate in my unit.”

So on March 16, he filed a federal lawsuit against his chain of command asking the U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado to declare a Defense Department Instruction restricting protest participation to be unconstitutional as applied to him and other off-duty reserve component troops.

The key distinction between Kennedy and other recent and historical cases of discipline for protests or political speech — such as the sailor who was punished last year for yelling “f*** Trump” and the soldier who was disciplined when two reservists from American Samoa appeared in a video at the 2020 Democratic National Convention — is that the JAG was not on military orders during the protests, nor was he wearing his uniform.

RELATED

And on Sunday, Kennedy learned that Army Brig. Gen. Laura Clellan, the state’s adjutant general, had ordered an investigation into the state’s chief of staff, Army Col. Charles Beatty, and other officers for their conduct in handling his case.

Kennedy emphasized that he doesn’t want his case to overshadow the cause he supports, though.

“My fight for constitutional rights pales in comparison to the persecution of George Floyd and Daunte Wright, and countless others who have been murdered by the police,” he said.

The Colorado National Guard declined to provide Military Times with an update on the investigation into Beatty and others, which was originally due for submission on April 15. It is unclear whether the investigating officer has submitted findings and recommendations yet.

“Capt. Alan Kennedy’s branch of service is the Colorado Army National Guard,” confirmed 2nd Lt. Katherine Lee, the Colorado Guard’s deputy state public affairs officer, in an email to Military Times. “Due to ongoing litigation, we cannot comment on [your] other questions.”

Beatty, the Colorado Guard’s chief of staff, said via text message that he also was “unable to comment” due to the ongoing litigation.

And during the investigation, Clellan, the adjutant general, has also ordered that the state will not punish any troops for violating the DoD instruction that Beatty allegedly misapplied. That means Kennedy is free to protest...for now.

The initial investigations of Kennedy

Kennedy first earned the scrutiny of his Guard superiors for a October 2019 New York Times video op-ed criticizing the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw American troops in the face of a Turkish military operation against Kurdish forces who had borne the brunt of the anti-ISIS campaign.

An investigating officer found that Kennedy “did not violate any prohibitions, limitations, standards, or polices with regard to exercise of political activities, use of media, or ethical standards.” Even active-duty members of the military are permitted to write letters to the editor, op-eds, or other opinion news pieces, so long as there is a disclaimer.

But the saga began anew when Kennedy wrote an op-ed in June 2020 detailing his participation in a peaceful daytime march in Denver that ended with tear gas and flashbangs from Denver police. “The police I encountered did not give any notice, any warning, before firing tear gas and flash bang grenades at marchers and journalists,” said Kennedy in the article.

He was not in a duty status at the time of the protest.

The only reference to Kennedy’s military service was in his two-line bio, which also included a disclaimer. “Alan Kennedy is a captain in the Colorado Army National Guard and a Ph.D. student at the University of Colorado Denver School of Public Affairs. The views expressed are his own.”

The op-ed published before dawn. Before dusk, Beatty, chief of staff of the Colorado Army National Guard and a defendant in the suit, had ordered an investigation into Kennedy’s protest participation and op-ed, according to the complaint.

In his findings and recommendations memorandum submitted on June 18, 2020, the investigator, Army Lt. Col. Christopher Lowman, wrote that Kennedy’s protest participation and op-ed “did not violate…any regulations, prohibitions, limitations, guidance, standards, policies, or federal statute,” save for what Lowman called a “minor” issue with his disclaimer statement, which should have clarified that Kennedy’s views were not an official position of the Defense Department or the Colorado Guard.

“I recommend CPT Kennedy update his disclaimer,” said Lowman. “I consider this a minor violation of the Army regulatory requirement that is easily corrected without any punitive actions required.”

Moreover, Lowman said that Kennedy did not violate Department of Defense Instruction 1325.06, which prohibits off-duty troops from “participating in off-post demonstrations…[where] violence is likely to result.” The investigator found “nothing in news or guidance that the march CPT Kennedy attended was expected to include violence,” stating that “he should not be held accountable for any activity that transpired out of his control.”

But Beatty, the chief of staff, modified the findings of the investigation to say that Lowman, the investigating officer “did not correctly interpret DoDI 1325.06 pertaining to the likelihood of violence occurring at protests. Objective review and a reasonable look at the circumstances surrounding the date of the protest indicate violence was likely to occur.”

Beatty also overrode the investigator’s recommendation not to punish Kennedy, and directed his commander, Maj. Richard Sandrock — also a defendant in the lawsuit — to write a local memorandum of reprimand as a form of administrative punishment. Sandrock issued the reprimand on July 12.

According to an investigation appointment memorandum obtained by Military Times, the Colorado National Guard is formally investigating Beatty, Sandrock, and Col. Keith Robinson, the state’s staff judge advocate, for their handling of their investigation of the Denver Post op-ed.

The new investigator is working to determine whether all three “failed to preserve CPT Kennedy’s right of expression to the maximum extent possible,” in addition to whether Beatty “improperly investigated” Kennedy and “improperly modified the findings of the Investigating Officer.”

The first reprimand itself is subject to the investigation as well — including whether “MAJ Richard Sandrock improperly reprimanded CPT Kennedy in violation of AR 600-37” and if Beatty “improperly ordered MAJ Sandrock to issue a letter of reprimand to CPT Kennedy through incorrect application of DoDI 1325.06…in violation of AR 600-37.”

The second reprimand — “limitations on one’s rights”

“You are hereby reprimanded,” began the permanent general officer memorandum of reprimand — a career killer often shorthanded as GOMOR — issued by Army Brig. Gen. Douglas Paul, the commander of the Colorado Army National Guard on September 11, 2020. “You fail to understand the most basic premise of military service: subordination of the self to the chain-of-command, including, in some instances, limitations on one’s rights.”

The subject of the GOMOR was a second op-ed that Kennedy wrote, this one about the first investigation. In the Colorado Newsline column — which sports an identical disclaimer to the Denver Post op-ed, because he wrote the column before Lowman had recommended he change the disclaimer — he spoke against the decision to investigate his protest participation.

In the reprimand, Paul criticized Kennedy and said the JAG “violated regulations and provisions of the Colorado Code of Military Justice, and your actions brought disrepute and dishonor upon the COARNG.” The reprimand did not cite which specific portion of the state military code Kennedy had violated, but the law prohibits “disrespect toward his or her superior commissioned officers.”

In a phone interview, Kennedy described the second reprimand as evidence of “a pattern of retaliation for constitutionally-protected activities,” and sought to have it overturned on appeal. “If I have been overzealous in pursuit of justice, it is because I felt a chilling effect on my rights,” wrote the civil rights attorney in his rebuttal memorandum dated October 18.

Paul denied Kennedy’s appeal on Dec. 5, and directed that the letter be permanently added to Kennedy’s personnel file.

The March 12 investigator appointment memorandum from Clellan, the state adjutant general, also asks the investigator to determine if Beatty, the state chief of staff who directed both the Denver Post and Colorado Newsline op-ed investigations, “improperly failed to provide CPT Kennedy due process during the course of the processing of the [GOMOR].”

Investigating Col. Beatty

Kennedy unsuccessfully appealed the GOMOR to the state’s adjutant general, Army Brig. Gen. Laura Clellan, and to the National Guard Bureau chief, Army Gen. Daniel Hokanson. Both officials informed Kennedy and his attorney that they did not have the authority to overturn the reprimand, and now both are named defendants in Kennedy’s lawsuit.

But both generals expressed concern over the allegations of reprisal.

Clellan took the step of appointing an out-of-state officer to conduct the investigation into the conduct of Beatty, Robinson, and others named in Kennedy’s allegations of administrative defects and constitutional violations.

“There is no place in our National Guard for reprisal,” said Gary Owens, NGB’s deputy general counsel for administrative law and ethics, in an email to Kennedy’s legal team obtained by Military Times. “[I] assure you that the CNGB [Hokanson] is taking your client’s concerns very seriously.”

The Colorado National Guard did not provide the findings and recommendation of the investigation, which was scheduled to be completed April 15, according to the appointment memorandum. Kennedy told Military Times he did not know if the investigation was complete, and the Colorado National Guard declined to answer any questions, citing the lawsuit.

The battle in the courtroom

The government has until May 17 to respond to Kennedy’s lawsuit. Assistant United States Attorney Jennifer Lake is heading the response to the challenge.

It’s unclear how the case will end, said Kennedy, because the courts “have never addressed the rights of part-time military reservists in a free speech and assembly context.”

Attorney Franklin Rosenblatt, a retired Army JAG lieutenant colonel and attorney at Butler Snow LLP in Mississippi, had to reach back to the American Revolution and the early 1800s to find cases similar to Kennedy’s.

“The core issue in this lawsuit — the reach of military discipline to off-duty speech and association — is as old as our nation itself,” said Rosenblatt in an email to Military Times. “The most hotly contested military justice cases in the United States’ early years concerned the accused’s status as a private citizen or militia member.”

“Historian Christopher Bray recounts a case from 1808 in which Maryland Federalist Jonathan Meredith offered a toast at a private dinner: ‘Damnation to Democracy!’ The court-martial transcript reveals that his defense was that he ‘appeared as a private citizen, and not in a military character,’” he added.

“Likewise, just after the American Revolution, Thomas Bevins admitted that he called his company commander a ‘damned Irish bugger’ who was unfit to command ‘any more than my dog.’ Bevins’ defense was that the statements were made at dinner when military duties were complete for the day, ‘when as men + gentlemen, we were on the same footing,’” said Rosenblatt.

How did those cases end?

“Bevins was convicted when at his court-martial it was revealed that he had also insulted his commander during the middle of the day,” said Rosenblatt. “[He was] clearly a soldier then.”

“Meredith was acquitted,” explained the retired JAG. “He did not deny making the statement but insisted that he was referring to French democracy — the bad kind — and not American democracy.”

So there likely aren’t any binding cases that are a great fit to guide the judge when considering Kennedy’s claims regarding his freedom of off-duty speech.

Temporarily free to protest

Meanwhile, Kennedy is temporarily free to protest while the investigations and lawsuits are under way. Clellan, the state adjutant general, issued an order Saturday stripping subordinate commanders of the authority to punish troops under DoDI 1335.06, paragraph 6(d) — the provision barring even off-duty troops from participating in protests where “violence is likely to occur.”

“Because the investigation is ongoing, I will exercise my discretion not to issue any disciplinary action [under the DoDI],” said Clellan. “This order does not constitute a judgement as to the appropriateness of any previous application of [the DoDI].”

Kennedy, while grateful that he can now participate in protests again without further disciplinary action, said that isn’t good enough. He wants a judge to strike down the rule altogether.

“As long as the unconstitutional provision of the DoDI exists, someone could decide to enforce it.”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.