Outlaw motorcycle and street gang activity across the Army dropped by more than half in fiscal year 2020, a stark contrast to the year prior, according to an internal assessment by Army Criminal Investigation Command, or CID.

Only 93 individuals with an Army connection were identified last year as being linked to gang activity through either a law enforcement report or a criminal intelligence report, according to the annual assessment, which was obtained by Army Times through the Freedom of Information Act.

The year before, that number was 245, according to the same annual assessment for 2019, also obtained by a FOIA request.

CID analysts cautioned in the document that last year’s precipitous drop could be attributed to limitations imposed by the coronavirus pandemic, such as curfews and the inability to gather in public without being noticed.

The document also warned of intelligence gaps. Some local police, including in California, stopped entering individuals into gang databases due to lawsuits, and gangs have shifted to more secure social media and encryption, “leaving a blind spot for law enforcement detection of gang activities,” the assessment reads.

Regardless, the drop chronicled in 2020 is significant.

“We have observed a decline in street gang and outlaw motorcycle gang activity,” said CID spokesman Chris Grey. “We believe this is a product of many years of education outreach, research and gathering data on gang-related crime, as well as an Army focus on training and leader awareness. Working in cooperation with Army law enforcement, Army leaders are better positioned to react and take action to counter indications of gang-related crime and participation.”

RELATED

Fifty-two of the 93 individuals identified by CID in 2020 were involved in street gangs, and 41 were involved in biker gangs. In 2019, the split was 101 linked to street gangs and 144 linked to biker gangs. Some of those people were civilian dependents or former service members, though most were currently serving.

Soldiers implicated in street gangs tended to be low-ranking. Biker gangs, though, had different trends.

A review of the 35 criminal intelligence reports related to biker gang activity showed that the soldiers involved ranged from private to major, with “a significant number” of noncommissioned officers between the ranks of sergeant and master sergeant, the assessment reads.

One example includes a December 2019 criminal intelligence report revealing that an active-duty staff sergeant was named by local police as a member of a support club for the Hells Angels. The soldier’s social media accounts had pictures of his biker vest with “1% patches,” a reference to the common refrain that 99 percent of motorcyclists are law-abiding citizens.

RELATED

Another incident in July 2020 involved an active-duty private who was assaulted at an off-post party. Authorities determined the service member had been “intimidated” by two other soldiers for “displaying a red bandana but not being a member of the Bloods street gang,” as they were, the assessment stated.

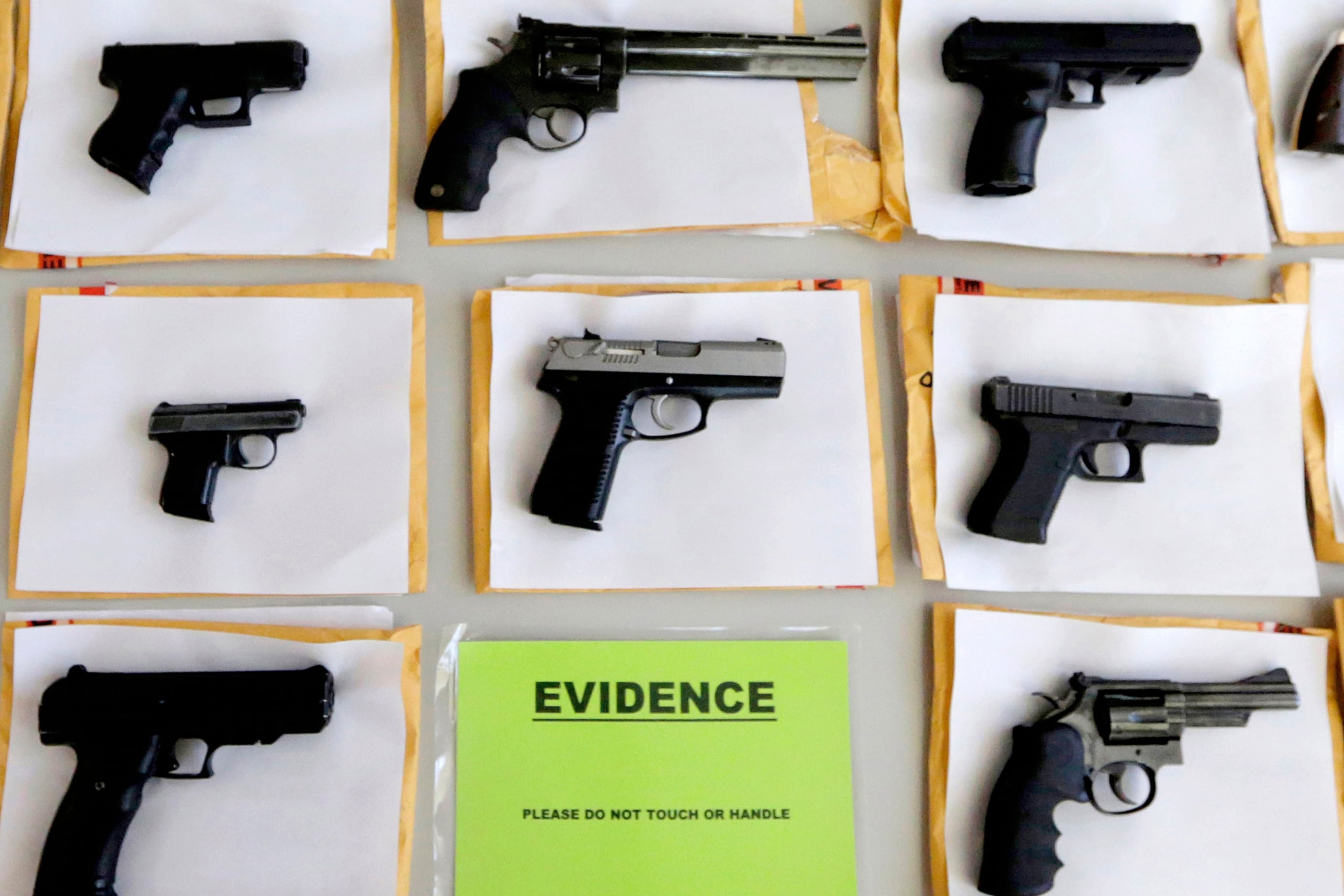

In a different incident in November 2019, local police executed a search warrant at the home of a specialist. They discovered four pounds of “marijuana, multiple firearms, ammunition, a large quantity of U.S. currency, a money counting machine, military body armor and packaging materials,” the assessment stated.

An investigation determined the soldier and their spouse were “verified members of Eight Tray Gangster Crips,” the assessment added.

Participation in street gangs, including wearing gang colors or having gang tattoos, is forbidden by Army regulation. Joining motorcycle gangs that use their clubs as conduits for criminal enterprises, like violent crime, weapons and drug-trafficking, is also verboten.

There are more than 300 active outlaw biker gangs within the United States, CID analysts said in the assessment. The groups range in size from single chapters with five or six members to hundreds of chapters with thousands of members worldwide.

“The Hells Angels, Mongols, Bandidos, Outlaws, and Sons of Silence, pose a serious national domestic threat and conduct the majority of criminal activity linked to [biker gangs],” the CID assessment reads. “Because of their transnational scope, these [biker gangs] are able to coordinate drug smuggling operations in partnership with major international drug-trafficking organizations.”

The assessment noted, however, that the overall threat posed by all gangs on Army installations is “Low.” Less than 1 percent of the more than 10,000 felony law enforcement reports catalogued by CID in 2020 involved known or suspected gang members.

Still, there are “many challenges in measuring and assessing the gang threats within the U.S. Army,” the assessment stated. Data is “somewhat limited” and what figures are available are “not necessarily comprehensive,” it added.

“Not all gang members are known to Army law enforcement, resulting in the underreporting of gang related activity,” the assessment reads. “Also contributing to this gap, the number of gang members in the Army is dynamic; new members enter undetected, gangs regularly seek new recruits and existing members move through permanent change of station and deployments.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.