He wore captain’s bars when the missile struck.

Nobody’s certain what kind of missile it was, even two decades after April 7, 2003. But whatever it was blew William Glaser, the headquarters company commander for the 3rd Infantry Division’s 2nd Brigade, out of his chair. Thick smoke rose from the brigade operations center into the Baghdad sky as dozens of vehicles burned.

Now-Brig. Gen. Glaser recounted that morning at a conference table in his air-conditioned Orlando, Fla., office, today one of the service’s top simulation officers and director of the Synthetic Training Environment development team.

Before the missile, the center buzzed with activity while Lt. Col. Eric Wesley, the Spartan Brigade’s executive officer, directed fire support and prepared a resupply mission to support the unit’s two armor battalions — Task Force 1-64 and Task Force 4-64.

After an audacious assault into downtown Baghdad, their tanks and Bradley Fighting Vehicles stood watch over key government buildings, including two of dictator Saddam Hussein’s most-prized palaces. The soldiers risked becoming mired in another Mogadishu, leaders feared, unless their infantry battalion held the supply lines open along Highway 8 in the face of increasingly fanatical counterattacks.

The brigade’s fate and that of the Thunder Run, named for the Vietnam-era armored reconnaissance missions that cleared mines and tripped ambushes, hung in the balance as the flames spread. In the weeks since the ground invasion began on March 20, the unit fought its way from the Kuwait border to the city’s outskirts.

And the Thunder Run, if the brigade could hold the city center, offered an irresistible opportunity to end the war and oust the Hussein government. Failure couldn’t happen this deep inside a hostile city of nearly 5 million people.

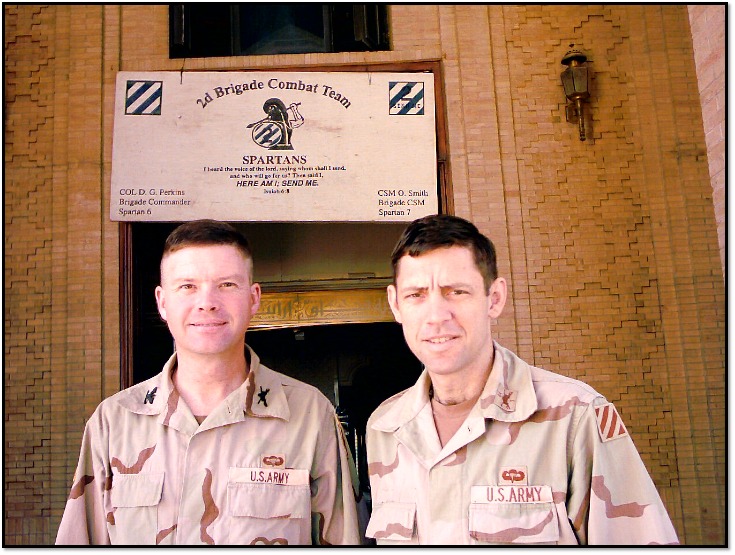

Ahead of the invasion’s twentieth anniversary, Army Times interviewed the brigade’s seven future generals and asked them to reflect on the Thunder Run and the role it played in their development as leaders. The candid conversations offer new insight into a tight-knit talent network that went on to reshape the service’s guiding concepts and doctrine, drawing on their experiences along Highway 8.

Wesley walked away from his Humvee shortly before impact, thanks to his nervous habit of pacing around while on the phone with his boss, brigade commander Col. David Perkins. The colonel was downtown with the tank battalions.

“We’re achieving all of our objectives…I said, ‘Congratulations, it’s everything we dreamed,’” Wesley, who retired in 2020 as a lieutenant general, recounted in a phone interview. Then the missile “rocked our world,” knocking him to the ground.

Perkins recalled hearing “an explosion or static” through the phone when the missile struck near the hood of Wesley’s vehicle, he told Army Times in a phone interview. Then a dazed Wesley told him the operations center was out of action and quickly hung up.

Another future general, Capt. Michelle Letcher, remained in the dark. For the entire invasion, her maintenance company rode with Task Force 1-64, keeping its tracks rolling with only the parts they carried. All of the battalion’s Abrams tanks entered Baghdad under their own power, despite running harder, faster and longer than any American armor unit.

But Perkins ordered most non-armored vehicles left behind at the city’s outskirts, fearing ambushes — leaving Letcher, later the service’s ordnance chief, wondering if the missile had killed the soldiers in her forward maintenance teams at the operations center.

While Glaser, Wesley, Letcher and Perkins, who retired as a four-star general and head of Army Training and Doctrine Command in 2018, worried about the missile strike, three other future general officers from the brigade fended off counter-attacks from dictator Saddam Hussein’s fanatical troops.

Captains Andrew Hilmes and Larry Burris served as company commanders in Task Force 1-64, built from 1st Battalion, 64th Armor and attached elements such as Burris’ infantry company.

Before the invasion, the two recalled over coffee in Burris’ Fort Benning, Georgia office, they made a trade: Hilmes took one of Burris’ infantry platoons, and Burris received four of Hilmes’ tanks. On April 7, they led the attack into Baghdad together — Hilmes’ company at the brigade’s vanguard, Burris’ soldiers immediately behind.

Lt. Col. Stephen Twitty, commander of a task force built on the 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry, directed the defense of Highway 8 — the critical north-south supply route that, if recaptured, would have allowed Iraqi forces to cut off the two tank battalions downtown.

The now-retired lieutenant general’s Bradley fended off suicide bombers with its 25mm auto-cannon, but his ammunition supply dwindled as his troops held three key interchanges. An improvised unit of headquarters troops down the road at Objective Curly, led by 1993 Battle of Mogadishu veteran Command Sgt. Maj. Robert Gallagher and a young staff captain, faced the longest odds.

But they prevailed. The resupply convoy got through, and the downtown units survived nighttime counterattacks. And when the fighting slackened on the afternoon of April 8, the Spartan Brigade’s leaders quickly realized their victory sealed the Hussein government’s fate.

It also changed their lives and launched their careers.

“History kinda thrust [the Thunder Run] upon us,” Perkins reflected. “And everyone rose to the occasion.”

The World Watching

The 2nd Brigade, a conventional armor brigade, epitomized the Army the United States had in 2003. The service picked the unit’s leaders through traditional assignment processes. They were ordinary officers.

But when they crashed through the border berm on March 20, the brigade’s soldiers found themselves on the invasion’s leading edge — an extraordinary opportunity on an unprecedented stage.

“This was not a hand-picked unit,” explained Hilmes, the lead company commander. “This is just the talent that the Army had and had brought together.”

Perkins laughed as he said the brigade was “an average Army unit.” He explained his leaders “were not, like, an all-star team. Who would have picked some colonel who had never been in combat before to be the brigade commander?”

Wesley, who later supervised the development of the Army’s multi-domain operations concept, emphasized how few units experienced the sweeping maneuver warfare that characterized the rapid destruction of Hussein’s army.

“A relatively small element of the ground armed forces — including the Marine Corps — experienced that two-week [period],” he said. “Not a lot of people experienced that.”

The brigade led the attack by chance. They deployed to Kuwait in September 2002 for Operation Desert Spring, a rotational desert warfare training mission dating back to 1998. The period acclimated and sharpened the brigade for when the order arrived.

Perkins did not expect to invade Iraq when he took command before the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, he said. But circumstance — and the Bush administration — demanded differently.

And thanks to Perkins, the world followed them into Baghdad and witnessed the brigade’s triumph on their television screens and the front pages of newspapers.

When the 2nd Brigade crossed the Kuwait-Iraq border, around two dozen journalists rode with them, Perkins said. They shared the soldiers’ hardships and dangers — three died alongside the brigade, one from a blood clot and two in the April 7 missile attack.

Wesley explained how his former brigade commander was ahead of his time in embracing the strategic opportunity that media coverage offered. Even after the April 5 attack up Highway 8, when Task Force 1-64 fought their way to the airport and set the stage for the larger Thunder Run, local Iraqis believed their government’s propaganda — they believed Americans were dying in droves at the city’s gates.

Glaser agreed, linking Perkins’ information savvy to the multi-domain operating concept now driving the Army’s new approach to war.

“[Perkins] clearly knew that…the Iraqis needed to understand that their army had been defeated — and killing more people wouldn’t do that,” the former headquarters company commander said. “But putting a tank brigade on the parade grounds in the center of Baghdad…and, more importantly, putting that on Fox News, the Iraqi people and specifically the army would understand they have been defeated.”

The colonel’s only ground rule for the media was “you can’t do anything that is going to put people in danger,” such as revealing battle plans or unit locations during live shots. In return, they received full access to any space.

Perkins described the relationship as one of “trust and empowerment” that relied on faith in the media to tell the full story. Even if disaster struck and soldiers killed civilians or others, he asked reporters to cover what his troops did in an effort to prevent it.

“If something bad happens, fine, report it happened. We’re not going to cover it up,” Perkins recalled saying. “But you need to contextualize — they’ve gone to great lengths to try to prevent this. I want you to tell the full story.”

Stars Born

All seven generals agreed the brigade’s success — or as Hilmes chuckled and said, “our secret sauce” — stemmed from that culture of trust, and their desert training experience strengthened it.

“If you get the command climate right…any Army unit can do this,” Perkins insisted.

The division’s deputy commander, now-Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin trusted Perkins after the training exercise helped them build a “mental playbook” together. As did his division and corps commanders.

On April 7, when Perkins and his superiors had to decide whether the tank battalions would stay in downtown Baghdad overnight, it wasn’t a “rash decision,” the brigade commander explained. “It was the culmination of…a year and a half of training and team building.”

Wesley said that Perkins’ trust-based approach, which extended down to subordinates, “gave a framework for people to operate within their own spheres of expertise and influence.”

It showed at the lowest levels, too.

“Every soldier — I don’t care how senior or junior — had this ‘send me’ attitude,” Letcher recalled. “I don’t want to call war special, but being part of something like that, you know, it is special.”

Glaser, the headquarters company commander, said trust and teamwork inspired “a huge wave of tan uniforms coming to the [operations center]” in the wake of the missile attack to help the wounded and salvage communications equipment. Barely an hour later, he and Wesley reestablished the brigade operations center.

Burris emphasized how their months spent training for Desert Spring cemented the trust and familiarity underlying their success. “We all recognized each other’s voices on the radio…I could tell what Andy [Hilmes] was dealing with, or he could hear what I was dealing with, just by the nature of the tone of our voices.”

The seven generals also acknowledged the Thunder Run propelled their careers. To an extent, the recognition — awards, media coverage, and more — they received provided a boost.

Four of the future generals received the Silver Star Medal — Perkins, Twitty, Burris and Hilmes. And Wesley received a Bronze Star Medal for valor. Subsequent promotion boards and peers valued such awards, and the combat experience they represent.

Gesturing towards Burris while refilling his coffee, Hilmes explained how the awards potentially helped them receive early promotions to major alongside the engineer company commander, David Hibner, who is today a senior civilian official leading the Army Geospatial Center.

“We were probably three of a handful of captains on that board who had Silver Stars,” Hilmes remarked. “The board probably did look at that and was like, ‘Wow.’”

The infantry school commandant, Burris, chimed in to agree.

Hilmes continued, arguing that their combat credentials alone couldn’t carry the captains past their initial promotion to major. But they helped him earn a role as the division commander’s aide-de-camp, a prestigious role that often expedites career progression.

The retired one-star acknowledged he had “some name recognition” after public speaking opportunities. His name also appears at least 16 times in the first four chapters of Thunder Run, a 2004 book by L.A. Times journalist David Zucchino, who embedded with the brigade during the invasion.

For Twitty and Wesley, both lieutenant colonels in April 2003, their exploits directly boosted their careers.

Twitty, the infantry battalion commander who attained three stars, recalled when fellow generals requested him by-name for deployments later in his career.

He was a one-star general assigned to Northern Command in 2009 when he received a call from Lt. Gen. William “Fuzzy” Webster, the new commander of the 3rd Army and U.S. Army Central. Webster wanted Twitty as his chief of staff.

“[Webster] remembered Moe, Larry and Curly well,” alluding to the three objectives that Twitty’s battalion defended, “and so he asked me to come to 3rd Army,” he recalled. A few years later, Gen. Ray Odierno also referenced the Thunder Run when selecting Twitty for a job.

“Without a doubt,” Twitty said when asked if April 2003 opened doors for him. “I heard it from their mouths.”

Wesley credited some of his success to his reputation from the Thunder Run and his battle-tested relationship with Perkins.

“I later worked for [now-Gen. and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff] Mark Milley…[when] I was a one-star in Afghanistan,” Wesley said, explaining that Milley didn’t know him personally before then. “But he knew me by reputation, as Perkins’ [executive officer] during the Thunder Run. And he voiced that to me.”

Others among the seven, like Glaser, said they didn’t notice a direct career impact. After his promotion to major, the now one-star general recalled, the Army reassigned him to a small simulations technology career field. That meant his relationships in the combat arms community and his Thunder Run experience somewhat diminished in relevance to his career progression.

Perkins, who rose the highest among the Spartan Brigade’s leaders, distinguished between the handful of opportunities the attack directly provided and those that stemmed from the potential for greater responsibility that his officers displayed in April 2003.

Although general officer promotion boards may consider their members’ personal knowledge of eligible officers, he said, becoming a general comes down to potential rather than performance because “they wouldn’t even be before this promotion board if they didn’t perform well…so I tried to differentiate between knowing somebody and somebody having the attributes that we need for potential.”

And yet, Perkins conceded, the Thunder Run presented a unique opportunity for his subordinates to prove their capability and potential to someone who himself had great potential. He discussed Hilmes, the lead company commander, as an example.

“Andy was in a tough spot at a tough time, and somebody that had maybe less foresight and [didn’t understand] the strategic implications of things, they may not have done well,” he said. “Had it been somebody else, they may not have made one-star. You can’t take away the fact that he rose to the occasion.”

But more importantly, all said, the Thunder Run’s success provided subtle confidence, which buoyed their subsequent trajectory through the tribulations of two decades of war to come. They’d demonstrated their potential under fire, on the biggest stage imaginable, and learned from it. They’d learned about life, combat and leadership and to instill trust.

Lessons Learned

But even for the advantages that the Thunder Run’s heroes enjoyed, they realized that the Army quickly moved on from the tactics and concepts that led to their success as the war devolved into one of bloody insurgency and occupation.

Now, as the Global War on Terror draws to a close for the service’s conventional troops, the seven generals report their experience and expertise are again hot commodities.

“We’re finding 20 years on that a lot of people are interested in that very small population that experienced that in 2003,” said Wesley.

Wesley is assisting Perkins to redevelop a capstone course at West Point about mission command doctrine, which emphasizes trust in subordinate leaders and gives them space to exercise initiative to exploit fleeting opportunities on the battlefield.

“We are continually amazed at what we learned that soldiers did [during the Thunder Run] that we never knew, because they were empowered to do them,” Wesley explained, recalling “countless stories of people taking initiative to make shit happen.”

Burris, now the infantry school’s commandant, is responsible for updating doctrine and tactical manuals for the branch. The process occurs every few years.

“What I found is I rely on my experience back then as we update our doctrine or the tasks that we expect soldiers to be proficient in executing,” Burris said as he described the struggle to find others with his large-scale combat experience. “It’s [about] ensuring that the future generation has the doctrinal knowledge, the basis to make sure that they can do what a group of ordinary people like we did.”

Letcher served as a proponent of the service’s ordnance, or maintenance, career field before her current role as the Army Futures Command chief of staff.

“I was…the Army lead for the joint concept of contested logistics,” she said, describing the Thunder Run’s resupply operation as embodying the doctrinal idea “at a micro level.” Letcher said her experience successfully directing hasty, on-the-fly maintenance during the initial invasion without a guaranteed supply chain offers key lessons — such as systematically stripping parts from destroyed vehicles — for maintainers in future large-scale conflicts.

But the end of the wars and the invasion’s 20th anniversary has some among the seven thinking about everything that followed the Thunder Run, and the six soldiers lost in Baghdad. The brigade had dozens more troops wounded — nearly 90 Spartans in total received Purple Hearts before the brigade returned home.

Staff Sgt. Stevon Booker, one of Hilmes’ tank commanders, was killed by enemy machine gun fire on April 5 during the first Thunder Run up Highway 8 to the airport. He received the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously.

The April 7 missile attack on the operations center instantly killed Spc. George Mitchell in the driver’s seat of his Humvee, and shrapnel killed 19-year-old Pfc. Anthony Miller. Perkins’ driver, Cpl. Henry Brown received serious burns and later died despite remaining conscious through his evacuation.

Two resupply convoy members, Sgt. 1st. Class John Marshall and Staff Sgt. John Stever, were killed in action on April 7 while fighting their way through an ambush to reach the units downtown.

Some see April 2003 as a turning point that defined their lives — but one that they’re still trying to wrap their minds around.

“Since that point in time, I feel like my life and my career have been on fast forward,” Hilmes, the service’s former top safety officer, said, mere weeks removed from his retirement ceremony. “In a lot of ways, I almost felt like I didn’t have time to properly process everything that happened in the first half of 2003…because the tempo and the pace of operations to go back to Iraq and Afghanistan was just unlike anything I’d ever seen.”

Looking back, he said, “this is an Army that’s never had a break.”

Burris, who fought side-by-side with Hilmes, nodded in agreement.

“I don’t know that I’ve processed what happened in 2003 yet,” the infantry commandant said. “I haven’t had the time to do it.”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.