Outstanding true stories from a doc in Iraq, a grunt and a photojournalist in Afghanistan, and an everyman in Vietnam. Also: Women who fight to fight, the future of war in reality and in video games, and skeletons and stupor in World War II.

Fiction? Fine work from the “Fobbit“ guy, a play from the U.K., and a former JAG’s legal thriller.

Here are autumn’s book reviews, listed in order of reading value and significance. All prices are suggested retail.

NONFICTION

Crossings: A Doctor-Soldier’s Story by Jon Kerstetter, Crown, 352 pages, $27.

He is an Oneida tribe member whose college adviser tells him Native students do not go into the “hard sciences.” But the Wisconsinite stepped across “the boundaries that scripted my life” before, and graduates from the Mayo medical school.

Not content with the “mundane side” of emergency medicine, he volunteers in Africa and Eastern Europe. Then, at 42, he joins the Army National Guard.

Why? “War engaged me.”

In three Iraq tours the flight surgeon savors “something provocative and empowering” in the risk of a potentially deadly encounter. “I needed the Army with all its attendant medical complexity and the stimulation of combat.”

Yet even he must “separate myself from the emotional impact of seeing the critically wounded” and of forensics ― identifying body parts. His descriptions are as visceral as mortuary-affairs Marine Jessica Goodell’s underrated 2011 memoir, “Shade It Black.” Kerstetter sees “things that even God might turn from seeing.”

Then, rushing to meet a medevac, he falls and breaks so many bones he finds himself on a gurney. Surgeries later, tests show a brain aneurysm. Then there’s a stroke that necessitates therapy that identifies ― surprise ― post-traumatic stress.

Despite the debilitating, frustrating diagnoses, the physician is convinced to heal himself, relearning how to walk and how to use words, and earning his master’s in writing. His rewriting his sentences and rewiring his body and his mind produce a remarkable story that is clinically clear yet emotionally eloquent, deserving of at least a Ph.D.

“I have had to constantly revise and rewrite the contents of this book,” he writes. Considering the high quality of the prose, the amazing admission inspires anyone who loves words.

Shooting Ghosts: A U.S. Marine, a Combat Photographer, and Their Journey Back from War by Thomas J. Brennan, USMC (ret.), and Finbarr O’Reilly, Viking, 340 pages, $27.

A Marine sergeant and a photojournalist walk into a war, willingly, and meet at Outpost Kunjak in Afghanistan. One is “a warrior, an active player,” the other is a “professional witness. He has a gun. I have a camera. He’s trained to follow orders. I’m programmed to question authority.”

Their shared memoir is “about how our stories became entangled,” with alternating chapters by each, sometimes offering two views of one event. The book about the effect of trauma is exceptional in candor and compassion ― and about the creative process.

“Writing is painful,” Brennan confides. “Not only the writing itself but grappling with my own experiences and emotions and self-doubt.”

Both men give examples of all three, some of their doubts triggered by being dumped by the military and by the media. One tries to kill himself.

Each discovers, says O’Reilly, that “the more I participate in my own life and expose myself to new experiences, the less trapped I feel by my memories.”

What memories. Brennan, medically discharged and mentally fragile after a grenade explosion, wonders “if it wouldn’t have been easier just to stay abroad” where he could “cling to a sense of normalcy amid the chaos of deployment.” At home he becomes an “asshole” toward his wife and daughter.

O’Reilly goes from the trying ’Stan to the fire in Gaza and finally sees enough. “There will always be another war. Just not for me.”

Each struggles to return to the “cadence and hum of life.” Brennan tries journalism boot camp (with O’Reilly as teacher), gets a journalism degree and publishes The War Horse digital report, which you’ve heard of. In March he broke the story about Marines United, the Facebook group that posted photographs of naked female Marines and embarrassed the Corps he loves.

The Odyssey of Echo Company: The 1968 Tet Offensive and the Epic Battle to Survive the Vietnam War by Doug Stanton, Scribner, 336 pages, $30.

The author of 2009’s popular “Horse Soldiers” (about Special Forces in Afghanistan and soon to be a movie) uses a title with a broad view but wisely narrows his focus. Army Spc. John S. “Stan” Parker enlists after high school and can hardly wait “to become a paratrooper and go to war.”

Stan gets his wish, and Stanton gets a soldier who exemplifies service in Vietnam. The combination makes a highly readable, dramatic, often heart-tugging story of the Tet effort from an all-American grunt’s viewpoint. Stan, who later wonders if he went to war “like a sucker and killed and bled,” personifies “a group of young men who survived something they often did not understand.”

What they know is that “America seemed to be at war both in the United States and in Vietnam,” and Stan “doesn’t know if he’ll still be alive at sundown” because war “is really about elimination ― eliminating, erasing, wasting, greasing, making nonexistent.”

Stan’s three Purple Heart citations vouch for that. He survives a bamboo spike that pierces his wrist, a leech as “thick as a hammer handle” on his eyelid, and the anxiety of trying to protect a starving girl, age “6 or 7,” while “wanting to come back to Vietnam as another kind of person and be able to offer her some peace and attention and safety.”

He returns 46 years later as a retired sergeant major and finds “a kind of transformation, a transubstantiation, even” that brings him and a former North Vietnamese soldier ― and a reader ― peace.

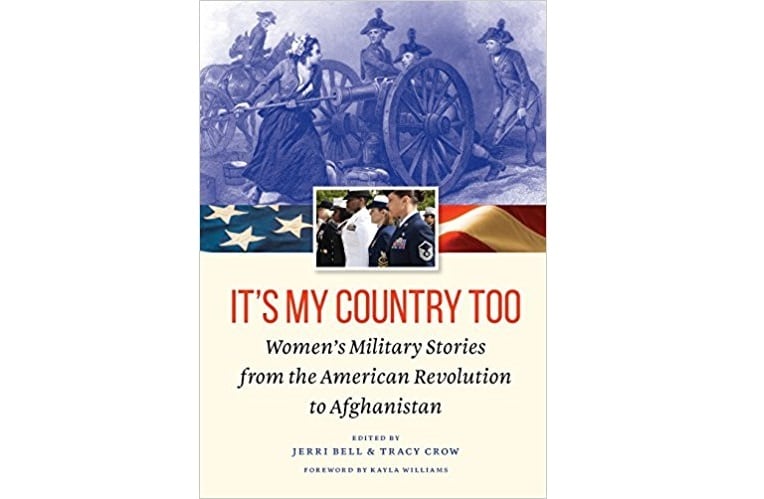

It’s My Country Too: Women’s Military Stories from the American Revolution to Afghanistan edited by Jerri Bell and Tracy Crow, Potomac, 376 pages, $33.

Prudence Cummings Wright, the leader of a female militia guarding a bridge during the Revolutionary War in which “a few hundred women may have fought in uniform,” opens the anthology.

Slow-forward 241 years to an era in which “280,000 women served in Iraq and Afghanistan,” and the book closes with Ranger School graduate Capt. Kristen Griest’s appointment as “the first woman assigned to a job in infantry.”

You’ve come a long way, slowly.

While collecting these essays and excerpts, the editors, both veterans, realize “we had served our own country without knowing our own history” and do not know “whose shoulders we were standing on.” In her foreword, author and veteran Kayla Williams says service women “were scattered, hidden, erased and hard to uncover. Until this volume.”

The welcome chronology attempts to show that “American’s fighting women have been ― and remain ― patriots and warriors,” and its stories might empower servicewomen ― and many of their brothers in arms ― to stand tall. Just like Oscar-winner Ginger Rogers’ mother, Lela Leibrand, who was a sergeant in Marine Corps public affairs in World War I.

“We are not a fad by any means,” she said.

The Future of War: A History by Lawrence Freedman, Public Affairs, 400 pages, $30.

The title (set for release Oct. 10) promises a look ahead, but the subtitle’s reference to history seems to be a conundrum: How can a look into the future be a history?

Easily, in the erudite British war-studies professor’s engaging survey of how and why historians and writers ― of nonfiction, fiction and film ― bravely prognosticate. The theme is scholarly, but the tone is refreshingly popular: Tom Clancy makes the index, but von Clausewitz does not.

“How people imagined the wars of the future affected the conduct and course of those wars when they finally arrived,” Freedman says.

Almost. After the “spectacularly poor decision-making” that led to World War I, “there was no wishful thinking about the nature of war in the years leading up to the Second.” Korea, Vietnam and other fighting followed, and “the reputations of intervention” suffered after Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya, “although Syria was a poor advert for holding back” on intervening.

The attacks on 9/11 turn terrorism, “largely seen as an exceptional irritant and occasional inconvenience, into a cause of national trauma” and indicate that “the inherited scripts for the future of war were inadequate,” including “the desperation of fleeing refugees and the opportunities for terrorism.”

What else is ahead? China’s strength and Asia’s politics make the region “a likely setting for a great power war.” The U.S. remains “the only power with a truly global reach in conventional forces, but it can no longer assume straightforward victory even in the battles fought on its own terms,” which seem unlikely.

“The future of the future of war is likely to contain speculative scenarios and anxious warnings, along with sudden demands for new thinking.” But predictions “should all be treated skeptically.”

Future War: Preparing for the New Global Battlefield by Robert H. Latiff, Knopf, 208 pages, $25.

Back to the “Future,” but the focus is technology with a touch of citizenry.

The retired Air Force general talks ― you can imagine his reading the text as a speech ― about “how new technology has changed and will change warfare,” and how developments “will challenge soldiers, decision makers and the public.” Well-equipped, “the soldier of the future will be a collection of data points.”

He pleads for assurance that America’s quest for “safety and security” is “compatible with morality and ethics.” Everyone ought to log in ― the military, the media, defense industries, and Americans who “thank soldiers for their service while thanking their lucky stars they don’t have to serve.” Otherwise “we may find we have a first-rate military and a second-rate society.”

Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich by Norman Ohler, translated by Shaun Whiteside, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 304 pages, $28.

Thanks to a “volksdroge” ― people’s drug ― called Pervitin, methamphetamine is everywhere in the German military, and pharmaceuticals fuel what is literally the “high command” ― including Hitler.

The author attributes some of the German armed forces’ allegiance, arrogance and aggression to chemicals, which enables his use of clever headings such as “Sieg High” for “Sieg Heil” and “High Hitler” for “Heil Hitler.”

He documents the Fuhrer’s use of cocaine, hormones, steroids and opioids from autumn 1941 into the second half of 1944: “Hitler hardly enjoyed a sober day.” The stupor allows him make mistakes as commander in chief and to “blissfully commit his crimes.”

Fortunately for the Allies, the Nazi “reign of terror was poisoning itself from within” while providing fascinating details Ohler presents today.

A Crime in the Family: A World War II Secret Buried in Silence ― and My Search for the Truth by Sacha Batthyany, translated by Anthea Bell, Da Capo Press, 224 pages, $28.

Maybe it’s the drugs: While the Nazi party fizzles, the party back at castle hops. It’s 1945, the Russians are coming, and German officers and fellow guests stop socializing long enough to go out and kill 180 Jews at an Austrian estate on the Hungarian border.

Does the hostess, the author’s great-aunt Margit, join the massacre? That’s the question that leads a Swiss journalist to investigate the action or inaction of Countess Thyssen-Batthyany (of the steel-rich Thyssens), who married into his once-aristocratic Hungarian family.

Sacha engrossingly uses diary entries, a script, email notes and a shrink’s couch to unfold layers of guilt. To his credit as a writer, his grandmother Maritta’s obsession about a childhood moral dilemma regarding her Jewish neighbors is as haunting as Margit’s dance card. The book is due out Oct. 10.

America’s Digital Army: Games at Work and War by Robertson Allen, Nebraska, 240 pages, $30.

The “Army” in the title includes everyone with a finger on the official Army video game, “America’s Army.” From soldiers, developers and marketers on the production side to players, there are many hands ― 40 million downloads and counting.

No longer a mere recruiting tool, the Army “does not need or expect every player of the game to be completely persuaded to enlist,” says the anthropologist. Why not? Because players, who are virtual soldiers, become militarized and “more readily accept the status quo of army (sic) norms, priorities and ways of thinking about the world.” Through interactivity, the Army integrates cultures.

Allen’s own months of “embed” fieldwork include “taking an introductory Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) course.” At a California game-production studio he finds staffers in combat uniforms, “freshly returned from a voluntary five-day job-related excursion” and “resocialization” at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, for “mini” Basic Combat Training and haircuts.

“In this work environment the developers adopted to varying degrees the subjectivities of the soldiers,” and the “military-entertainment complex” wins.

The Golden Fleece: High-Risk Adventure at West Point by Tom Carhart, Potomac, 224 pages, $30.

Getting the Navy’s goat is an infamous tradition and the point of this memoir by a U.S. Military Academy Class of 1966 graduate ― incidentally, he’s the Air Force brat who “longed to be the perfect cadet” in Rick Atkinson’s acclaimed 2009 book about West Point, “The Long Gray Line.”

To commemorate their last Army-Navy football game before graduation, Carhart and five classmates capture the mascot and cause ripples in the Hudson and the Potomac. A current cadet could adapt the antics into a field order this football season.

For something meatier, try Ted Russ’ suspense novel “Spirit Mission,” which combines a similar tail with a secret quest in Iraq ― and is on Military Times’ list of best books of 2016.

The Vietnam War: 1945-1975 by David Parsons, Marci Reaven and Lily Wong, New-York Historical Society and Giles, 96 pages, $18.

Slim, succinct, smartly designed, the book offers an objective chronology of a time when “27 million American men came of draft age [and] 2.7 million were sent to Vietnam.”

With six essays and storytelling images including a two-page stunner ― a 1968 photograph of Marines dwarfed by elephant grass that symbolizes morass ― the content shows many sides. A page about 1971’s Kent State shootings faces a page about 1970’s Hard Hat Riot, which supported the war.

Coinciding with an exhibit (through April 22) at the Historical Society, the 30-year timeline works well as an introduction to or a refresher about the conflict. It also unwittingly reminds a reader that “protester” is spelled with an “-er” – not an “-or,” and certainly not both ways.

Behind the Scenes: The Tales of American Military Spouses Making a Difference ― a Military Spouse Legacy Project coordinated by Cara Loken, CreateSpace, 222 pages, $14.

The collection lacks the polish that can come from a major publisher but makes up for design deficiency with pluck, starting with its first essay, by “a 38-year-old male military spouse in an interracial, same-sex marriage” who is voted president of his Navy husband’s Family Readiness Group.

The other 29 essays, representing all service branches, 27 women and two other men, demonstrate how singular initiative can have wide impact, from the creation of nonprofit organizations to a recognition that spouses can and want to have professions, also.

Many of the writers are recipients of what appear to be well-deserved spouse-of-the-year awards, and each offers advice about how to serve alongside those who wear the uniform in the family.

27 Articles by T.E. Lawrence, Simon & Schuster, 64 pages, $10.

One hundred years after their first publication, Lawrence of Arabia’s succinct but often stereotyping tips about how to work with Arab people are back.

The biographer John Hulsman’s introduction says Lawrence offers “a whole different worldview for how to work with others,” and CBS News head David Rhodes’ afterword admits Lawrence’s flaws, but says the advice still applies in “today’s global, asymmetric, information-overloaded challenges.”

Heed Lawrence’s suggestion to “cling tight to your sense of humour” while you try to forgive his condescending generalizations about entire cultures, such as: “If you want a sophisticated (servant), you will probably have to take an Egyptian, or a Sudani.”

In the Warlords’ Shadow: Special Operations Forces, the Afghans, and Their Fight Against the Taliban by Daniel R. Green, Naval Institute, 264 pages, $30.

The author of three books, including this one, is a Navy Reserve officer and Washington think-tank fellow who has deployed five times to Afghanistan and Iraq in military and civilian roles.

You can tell he knows what he is talking about, especially after his 2012 surveys (qualitative and quantitative) of sites where Army Special Forces and Navy SEAL teams try to enlist local support for defeating the Taliban. And if his style is academic (he tends to “reflect upon” things), his message is worthwhile:

“Too frequently, ‘victory’ is described in conventional terms ... when actual ‘victory’ has more to do with the ability of the indigenous government to handle its own internal security threats in the long term.”

The Last Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Final Combat Mission of World War II by Don Brown with Capt. Jerry Yellin, Regnery, 352 pages, $26.

A former Navy JAG officer and author salutes the U.S. Army Air Force’s 78th Fighter Squadron in this in this quick history of the Pacific aviators’ final months before Japan’s surrender.

The pilot ― Yellin, now 93 ― loses 11 friends in “their final rendezvous with destiny,” and the “impending aerial assault on Japan would lay the groundwork for the Allies’ planned invasion of the island.” Yellin’s 19-year-old buddy, 1st Lt. Philip Schlamberg, is “the last known combat death of World War II” and the great-uncle of actress Scarlett Johansson, a relationship the book mentions at least thrice ― as though progeny were Schlamberg’s claim to fame.

Hilltop Doc: A Marine Corpsman Fighting Through the Mud and Blood of the Korean War by Leonard Adreon, BookBaby, 244 pages, $15.

After six decades, the veteran opens up a bit: “My experience there has lived with me every day.” Using similar language, he reminisces about his service in this short, personal recollection enhanced by photographs ― his and the Navy’s.

His prose and poetry share a stark theme: “We own the hill,” he says, but “we paid too much.”

The Final Mission of Extortion 17: Special Ops, Helicopter Support, SEAL Team Six, and the Deadliest Day of the U.S. War in Afghanistan by Ed Darack, Smithsonian, 256 pages, $25.

Originally an article in the Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine, the expanded version offers a plethora of details about flying machines ― and their abbreviations ― involved in the 2011 attack that killed 38 aboard an Army Chinook helicopter: a horrific, single-day milestone of the Afghanistan war.

The book notes that the crew members’ personal goals and professional training exemplify the “military’s relentless drive toward perfection” but uses a “diverse but interrelated” structure that is more often pedantic than compelling.

Bounty Hunter 4/3: My Life in Combat from Marine Scout Sniper to MARSOC by Jason Delgado with Chris Martin, St. Martin’s, 352 pages, $28

Delgado is one of four snipers featured in last spring’s “The Killing School,” and this story about growing up the Bronx, serving in Iraq and being Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command’s lead sniper instructor is his take on eight years in the “strange mix of bloodlust and brotherhood” of the Corps.

The writing is off the cuff, from his first kill (after a “rookie mistake”) and first dip (cherry Skoal) to being “hot back in the day” full of “one-night stands four days a week.”

The vernacular tries to hit the mark but often misses. For example, a lieutenant makes “just about the greatest call anyone has ever made in combat.” Compared to whom? And “all the guys were highly motivated and talented warriors.” How so?

FICTION

Brave Deeds by David Abrams, Black Cat, 256 pages, $16.

Five years after his superb, satirical first novel, “Fobbit,” and worth the wait, Army veteran Abrams leaves the base and goes AWOL with (mostly) brave dudes, a “cluster of dumb in the middle of Baghdad.”

Six characters in search of the memorial service for their beloved Staff Sgt. Raphael “Rafe” Morgan start with “Grand Theft Hummer,” in which they procure a Humvee “under the noses of gate guards more interested in mashing thumbs across Game Boys than the loss of one three-ton government vehicle.” The vehicle then breaks down.

The warriors, admitted “worriers,” proceed on foot, lost in urban space that is desolate and dangerous. With nearly every step they stumble into trouble ― and opt to check out a tip about possible bomb makers inside a nearby house. Instead, should they continue their harried and hurried way? Or will a successful search turn their unauthorized meandering into a mission that might merit official forgiveness?

Their decision spirals into conflicts, some personal: Fish’s psychopathic behavior and Cheever’s selfish whining. Drew and O’s distracting obsessions about their romances. Park’s reticence that is construed as arrogance. Arogapoulus’ new addiction that could indicate he is not the straight “Arrow” his men trust.

The dusty half-dozen speak with an omniscient, third-person voice that might cause some readers to wonder who “we” is. But no matter who’s talking, “our breath sucks and pitches in our lungs and we release what has been in there all this time.”

For the second time Abrams shows expertise at deft humor, which can let less-skilled writers fail. His crosstown caper ends up anything but funny, ultimately a touching, tense, and terrific look at young soldiers trying to find their way ― sometimes with guile and sadly without guidance.

Pink Mist by Owen Sheers, Talese, 112 pages, $27.

The Welsh author is “indebted to the many service personnel and their families whose stories have informed this work,” and readers of his play, in verse, will share the debt.

In the drama, three young British men enlist in the Army, aware that their service will include combat in Afghanistan, which is what they want. “Otherwise it’s like going to fair, but staying off the rides.” Off they go.

But “we came back, bringing ‘there’ with us ― the anger, the dreams, the dead” in a pink mist of exploding bodies. The language is dark and stark but offers hope, even when a veteran painfully stands on prosthetics to watch his mate’s coffin lower into the earth.

Reading a script means doing without the acoustics and kinetics of a stage production such as the National Theatre of Scotland’s outstanding “Black Watch” (about Iraq), which played in the U.S. But the drama deserves an audience over here.

Sapphire Pavilion: A Steve Stilwell Thriller by David E. Grogan, Camel Press, 280 pages, $16.

This is not about gems or architecture, and prior Stilwell experience is unnecessary.

All you need do is allow this suspense novel to entertain you with what happens when a former Navy JAG officer learns that an old Navy buddy is in a Ho Chi Minh City jail for possessing heroin.

The situation brings international, military and political intrigue, a secretary of state who is tight-lipped about a relationship that goes back to when the city was called Saigon, a female agent who’ll muster any mystique for money, an Iraq veteran starting what she thinks will be a no-stress job at a small law firm in colonial Williamsburg, and a Vietnamese taxi driver who wants to get his family to the U.S. And there’s Stilwell, whose billable hours do not help his marital life.

Throw in elements of bribery, treachery and ethics, and you’re hooked by the former Navy JAG officer’s second novel.

Operation Jericho by Jonathan Ball, Morgan James, 240 pages, $17.

The Marine veteran’s action novel, released in 2013 and now in a new edition, tells the poignant story of two heroic Marine sergeants who are Muslim-American brothers on CIA duty in Afghanistan.

The writer is earnest in his effort to demonstrate that motivated Americans in the military include Muslim ones, an enlightening view while immigration laws are in the news.

However, Iman and Hasim, whose parents moved from Afghanistan to the U.S. during the Soviet conflict, come across as the Didactic Duo.

The pair has “an unnatural ability to move quickly through open terrain,” thanks to Corps training. And after infiltrating a terrorist camp, they see firsthand “why American heroes, especially those brave enough to serve in the U.S. Marine Corps, were such a phenomenal and effective force all over the world.”

The messages are superfluous and demonstrate that the pen is heavier than the sword.

Osiris by Eric C. Anderson, Dunn, 212 pages, $19.

The “retired member of the U.S. intelligence community” offers what seem like credible details in his thriller about what happens when ISIS tries to make up for “a thousand years” of humiliation by the West. Today, they want Baghdad; tomorrow, Jerusalem. They’re off to an audacious start by trapping 5,000 U.S. Embassy workers in the Emerald City.

With rapid pace, Anderson introduces Turks, Russians, Qataris, a Marine who works with the CIA, an Arab-American officer in the U.S. Army, and the mysterious cyber warrior they call ODIN. You don’t have to guess who the bad guys are. (There’s also a female, and she’s bad, for personal reasons.)

Suspense develops but characters do not. “This is the first book in a trilogy,” the jacket says. Perhaps the next two will have individuals who are as intriguing as the action.

NONFICTION NOTED, NOT REVIEWED

Victory! Applying the Proven Principles of Military Strategy to Achieve Greater Success in Your Business & Personal Life by Brian Tracy, TarcherPerigree, 320 pages, $17. The author of 80 books says “you can become extremely successful by doing what other top military leaders and business executives have done.” His examples span from King Pyrrhus in Asculum in 279 B.C. to Army Gen. Tommy Franks in Afghanistan in 2001.

End of the Saga: The Maritime Evacuation of South Vietnam and Cambodia by Malcolm Muir Jr., U.S Navy History and Heritage Command. In the Navy’s ninth book about the Vietnam war, sailors and Marines save “thousands of U.S. citizens and pro-American Vietnamese and Cambodians from the Communist forces in the spring of 1975.” Available through Government Printing Office or via free download here.

Crashback: The Power Clash Between the U.S. and China in the Pacific by Michael Fabey, Scribner, 316 pages, $26. “China and the United States ― and particularly the U.S. Navy ― are engaged in a warm war in the Western Pacific,” says military and naval-affairs writer, and “the U.S. has been losing.”

On Tactics: A Theory of Victory in Battle by B.A. Friedman, Naval Institute, 256 pages, $30. Tired of tactics taking a back seat to strategy, the Marine major theorizes about tactics in a book for those who study war.

War by Numbers: Understanding Conventional Combat by Christopher A. Lawrence, Potomac, 498 pages, $40. Crunching the numbers shows that “defense is the stronger form of combat.”

The Women Who Flew for Hitler: A True Story of Soaring Ambition and Searing Rivalry by Clare Mulley, St. Martin’s Press, 496 pages, $28. The sky wasn’t big enough to hold both these test pilots who received the Iron Cross for service to the Reich. But as the war goes on, one wants to save the Fuhrer and the other wants him dead.

The Secret Genesis of Area 51 by T.D. Barnes, History Press, 192 pages, $22. The Army veteran of the Korean War worked at Area 51, the Nevada base established by the CIA in 1955, and provides a history of the “technology laboratory and business that continues today.”

Improvising a War: The Pentagon Years, 1965-1967: Reminiscences of an Untried Warrior by Benjamin L. Landis, Merriam, 186 pages, $12. A personal take about the Army’s coping with “the challenge to meet the force requested” in Vietnam without tapping the National Guard or Reserve.

FICTION NOTED, NOT REVIEWED

Execute Authority: A Delta Force Novel by Dalton Fury, St. Martin’s, 304 pages, $27. The “explosive conclusion” of the series about Racer Raynor by the former Delta Force soldier and late author whose Tora Bora memoir, “Kill Bin Laden,” was published in 2008.

In Plain Sight: A Jon Wells Novel by Greg Gardner, Calumet, 292 pages, $16. In this thriller by a retired Navy officer, former Army officer Wells investigates Somalian residents in Minneapolis, recruiting efforts by ISIS, and cyber-espionage by China.

Borland’s Sorrow by Philip A. Fortnam, iUniverse, 306 pages, $19. A Navy Reserve officer’s novel about a fourth-grade teacher who deploys to Iraq in 2003 with his Army National Guard unit and is wounded physically and mentally ― and redeploys in 2008.

Heavy Green: The Collision of Two Unlikely Missions in America’s Secret War by Sam Lightner Jr., Summits & Crux, 310 pages, $15. The climber and writer uses historical fiction to describe a covert Air Force and CIA effort to establish radar communications on a Laos mountain top during the Vietnam War.

Kiss the Talisman by Howard Moss, Daniel Wetta, 256 pages, $15. Also during the Vietnam War: A novel by a retired Air Force colonel tells the story of an Air Force captain who flies Phantom jets over Laos and finds love with a Thai woman.