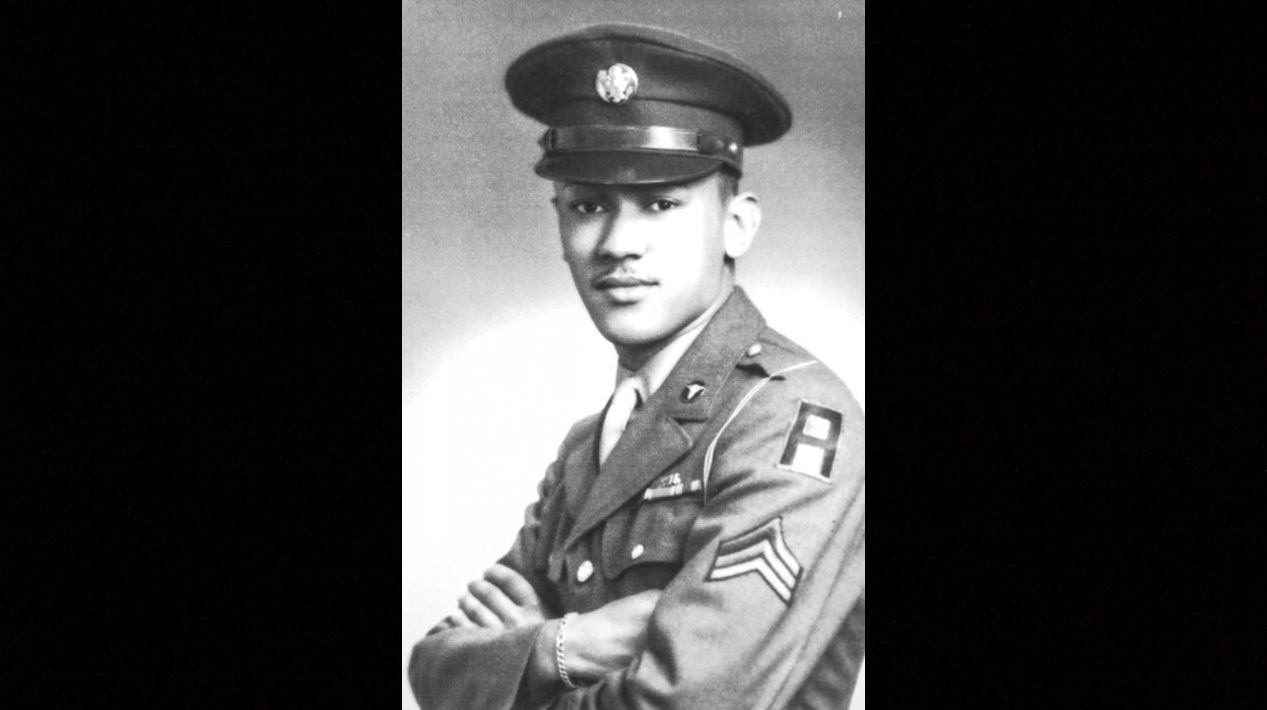

There is a push to review the case of an African-American combat medic who was wounded off Omaha Beach on D-Day while still aboard his landing craft but who fought through the injuries and spent the next 30 hours saving lives until ultimately collapsing.

Cpl. Waverly B. Woodson Jr., an Army medic assigned to a segregated combat unit, the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion, was wounded by shrapnel in his groin and back as his landing craft crushed through the choppy waters off the coast of France on June 6, 1944.

“Corporal Woodson was a hero who saved dozens, if not hundreds, of lives on Omaha Beach. His courage deserves to be honored with the Medal of Honor, and I continue to work with the Army to make this a reality,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., in a statement.

Woodson died in 2005 and received the Bronze Star for his actions, but his widow has lobbied for an upgrade. The case has been backed by a memo unearthed in 2015 that appears to indicate Woodson was originally considered for the Medal of Honor, but ultimately did not receive it due to his skin color.

A letter sent by Van Hollen and members of the Congressional Black Caucus on Wednesday asked that Acting Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy open a review into Woodson’s case.

Woodson’s commanding officer recommended him for a Distinguished Service Cross. But in a memo to the Roosevelt White House from War Department aide Philleo Nash, the recommendation was made for the nation’s highest combat medal instead.

“Here is a Negro from Philadelphia who has been recommended for a suitable award. He was first recommended by his C.O. for a Distinguished Service Cross, but General Lee’s offices said the act merited a Congressional medal," the memo, cited by Van Hollen’s letter, reads. "This is a big enough award so that the President can give it personally.”

That memo surfaced in the 2015 book “Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, At Home and At War," after the book’s author uncovered it in the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library.

“Based on extensive research on his service record, it is clear that Cpl. Woodson did not receive the Medal of Honor during WWII because of the color of his skin,” the letter to McCarthy reads. “We believe that the Army has sufficient evidence of the required recommendation to, at a minimum, permit a formal review by an award decision authority.”

Despite there being many segregated African-American combat units during World War II, no black soldiers were ever awarded the Medal of Honor.

Many point to Woodson’s record on D-Day as one instance of a black soldier who deserved the award.

After watching the man next to him die on the landing craft and being wounded by shrapnel himself, Woodson spent more than a day removing bullets, dispensing blood plasma, cleaning wounds, resetting broken bones, at one point amputating a foot and saving four men from drowning, according to the History Channel.

He only stopped after collapsing from his own wounds and being forced to evacuate to a hospital ship.

“He said that the men were just dropping, just dropping so fast. Some of them were so wounded, there was nothing that you could do but just give them a few little last rites,” Joann Woodson, 90, told CBS news last month.

Even immediately following D-Day, Woodson’s exploits were already being recognized in newspapers that reported on the black community in America as well as Stars and Stripes, according to the History Channel.

“Corporal Woodson was a true American hero who selflessly and courageously risked his life to save the lives of his fellow soldiers,” Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Md., said in a statement. “It is time to right the wrongs of the past and award Corporal Woodson the Medal of Honor to recognize his exceptional service to our country.”

In 1993 the Army contracted Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, to determine if there was a racial disparity in the way Medal of Honor recipients were selected, according to the Army Center of Military History.

The team did indeed find a disparity, and recommended the Army consider a group of 10 soldiers for the Medal of Honor. Of those 10, seven were recommended to receive the award.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.