FORT EUSTIS, Va. – Twelve soldiers — their backs ramrod straight, sweaty and spattered in mud — lowered to the grass in unison. They were doing pushups the right way — the Army way — with their elbows tucked close to their bodies.

These Eustis soldiers, hand-selected by their command, are among the Army's newest "master fitness trainers" — the service's solution to cutting flab, reducing physical injuries and revolutionizing unit PT.

The Army is in the middle of training thousands of these fitness gurus, who will be schooled in more than 150 exercises and dispatched to every installation and every unit, down to the company level in the active force, Guard and Reserve.

Army Times was invited to witness the learning process for this latest crop of trainers, who are taught by teams of contractors and active-duty troops who have studied the Army's overhauled fitness regime, dubbed Physical Readiness Training.

Calling PRT a "reset," officials say it's the biggest change to Army fitness since the 1980s. It's focused not only on exercise but also nutrition and physiology.

"The biggest thing is precision," explained master fitness course team lead Capt. Amy Tang, of the Army Physical Fitness School at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. "It's changed the DNA of the Army, just having the [training] teams go to installations, teaching [trainees] what the field manual won't teach. They can ask us any questions they have."

Since it began, the four-week courses have graduated more than 2,000 MFTs. Selected for their intelligence, leadership ability and superior Army Physical Fitness Test scores, these soldiers serve as resident experts for commanders who the Army requires to field their own PRT-based fitness programs.

The key to the program is that commanders have discretion, and are encouraged, to employ these fitness trainers as they are needed. If members of the unit are packing on too many pounds, the trainer can design a workout emphasizing weight loss. Or, say it's an artillery unit — the commander can use his master fitness trainer to target upper body strength.

Another goal, stated or not, is to woo troops from so-called extreme commercial programs like Crossfit toward the Army's new way, codified in Army Field Manual 7-22.

High-intensity training, done wrong, can cause problems ranging from torn ligaments to rhabdomyolysis, a condition in which muscles break down and release toxins into the bloodstream.

Tang noted PRT's strength-training circuits and the course's collective training make for safe but intense workouts in their own right.

"We're not here to bash any other programs," Tang said. "We're here to educate leaders and soldiers on the Army program."

Shaky start

The Army stutter-stepped into PRT, rolling out a comprehensive revision in 2010 and introducing it again in 2012 to the entire force.

Senior leaders acknowledge PRT has encountered some hiccups. Initially, commanders were slow to recommend their soldiers to the MFT course, which was competing against war-zone deployments, said Sergeant Major of the Army Raymond Chandler, the service's top enlisted official.

"We just didn't get the oomph behind it that we needed to inculcate it across the board," Chandler said via email. "We introduced it in [the Noncommissioned Officer Education System and Advanced Individual Training], but we never got it out to the operational Army like we should have, so it created some misperceptions about what it was about."

Not only that, but local leaders weren't buying into the program, either, Chandler said.

"So you saw other exercise programs that started to take root that were along the same lines of PRT. We needed to make sure that across the Army we had that buy-in and that understanding of the doctrine and implementation."

With the war in Afghanistan winding down, the time is right to refocus on PRT and train up more MFTs.

"We're trying to play catch-up after filling classes 50 to 60 percent," said Command Sgt. Maj. Thomas Campbell, of the operations, plans and training shop at the Army Center for Initial Military Training at Fort Eustis.

No more 'smoke sessions'

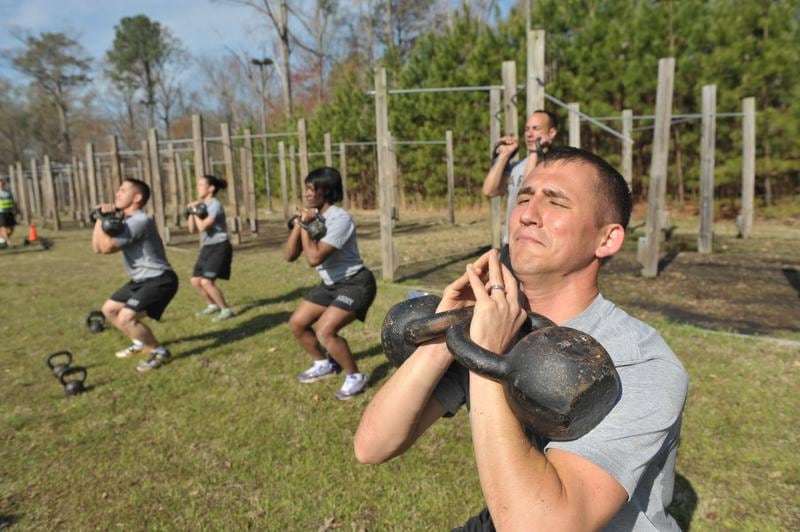

In the first week of the most recent round of training at Eustis, the experts took turns demonstrating at the front of the pack or walking between rows of exercising soldiers, correcting the fitness trainers-in-training on exercises like the "supine chest press" or "bent-over row."

Instructors with one of the Army's six mobile training teams supervised the 50 trainees, who were divided into small groups around a PT field left squishy by an overnight shower.

Though few trainees drop out, "this course is not easy," Tang said.

"If you're doing it right, it's a tough workout," said Sgt. 1st Class David Howell, an AIT platoon sergeant at Fort Eustis.

The course trains MFTs about the application of performance nutrition for soldiers. They learn how to determine the caloric and hydration needs of soldiers in various environments and activities.

Campbell and IMT Command Sgt. Maj. Dennis Woods, who were observing the training, agreed one of the program's main strengths and attractions for commanders is its focus on preventing injuries among soldiers, which can be a frustrating and expensive hindrance to readiness. For Woods, the program is a way to improve the overall physical health of soldiers without "breaking" them.

Chandler acknowledged that in a shrinking force, every soldier becomes that much more important.

"We've got to have more available soldiers," Chandler said. "So if we can do that by prevention, speedier injury recovery, and get more physically fit, I don't see how you can say there's anything wrong with this approach."

The Army's revised fitness regime also seeks to stop the practice of punishing problem soldiers with excessive PT known as "smoke sessions."

"Many times in these types of sessions, the difficulty, intensity, and volume of exercise is too high and the purpose may be to punish soldiers by bringing them to the point of exhaustion," according to Field Manual 7-22.

"This type of training is a dangerous practice that inhibits building resiliency because performance is degraded, motivation is lowered, and risk of injury is high."

That doesn't mean an NCO can't employ "corrective action" if necessary. The following exercises spelled out in the manual are OK to use, though only one may be used at a time: the rower, squat bender, windmill, prone row, pushup, V-up, leg tuck and twist, supine bicycle, swimmer and 8-count pushup.

Practical and precise

Each of PRT's exercises is functional, intended to build strength for specific soldier tasks. Though there are different ways to do a pushup, the PRT way is with elbows tucked close and hands close under the shoulders.

"Why we don't do pushups wide is you're working on the muscles that give you the most force to push," Tang said. "So if an enemy comes at you, and you have to push somebody away, those muscles are already developed."

Relying on a manual alone would make it difficult for units to properly perform the exercises, hence the need for MFTs.

The MFTs are meant to return to their units as acolytes of FM 7-22. The course they graduate includes classroom training on nutrition and exercise science, after morning drills to master the exercises themselves.

For the MFTs, it's considered a broadening assignment, according to Campbell, who said they could benefit at promotion boards for having the skill identifier.

Staff Sgt. David VanMeter, a trainee, described his unit's previous exploration of FM 7-22 as "informal." For example, he'd been using rear lunges to stretch his calves, because like a lot of folks, he thought that was the point of the exercise — but the course taught him the point is actually to stretch his hip flexors, extending his rear leg as far back as possible.

"That's why we're here at the school, to learn to do it correctly and properly," said VanMeter, a 27-year-old AIT platoon sergeant.

To VanMeter, the emphasis on precision was a reflection on the Army's back-to-basics direction.

Some trainees at Eustis already had ideas about how they wanted to contribute back in their units.

Sgt. 1st Class Michelle Loftus, with the post's McDonald Army Health Center, said she hoped to employ some of the functional movement lessons for her soldiers, who have to be fit enough to lift and carry litters in the war zone. Her soldiers, she said, could benefit from proper performance of "the windmill," an exercise that employs a twisting motion and strengthens the hamstrings.

Loftus also addresses supplement use among her soldiers, since surprisingly, medical personnel can make poor nutrition choices. She wants to educate soldiers about how to "eat clean."

"The thing I see a lot is improper supplementation, soldiers taking things when they don't understand what's in it," Loftus said. "Whether it's extreme dieting, or inappropriate techniques to get a desired effect ... Some soldiers are educated, and some are just following the fad."

Sgt. 1st Class Jeremy Logan, a long-distance runner whose emphasis is on endurance, said he got to practice pullups and hopes to pass along more specifics to soldiers about the rationale behind the prescribed form. Troops fresh from basic training, and often participating in their first structured fitness program, can show up to AIT with knee and hip injuries.

"Most people when they run, they don't pay attention to how they run," Logan said.

At Eustis, the course had four instructors; each has by now traveled to teach local soldiers at multiple Army installations. The instructors are, for the most part, certified in personal training and contractors with Anautics, of Newcastle, Okla.

After a demonstration of the overhead push press, which involves lifting kettlebells above one's head from a standing position, a soldier approached instructor Chelsea Vandermeer to double-check his form.

"You're catching on," she said.■