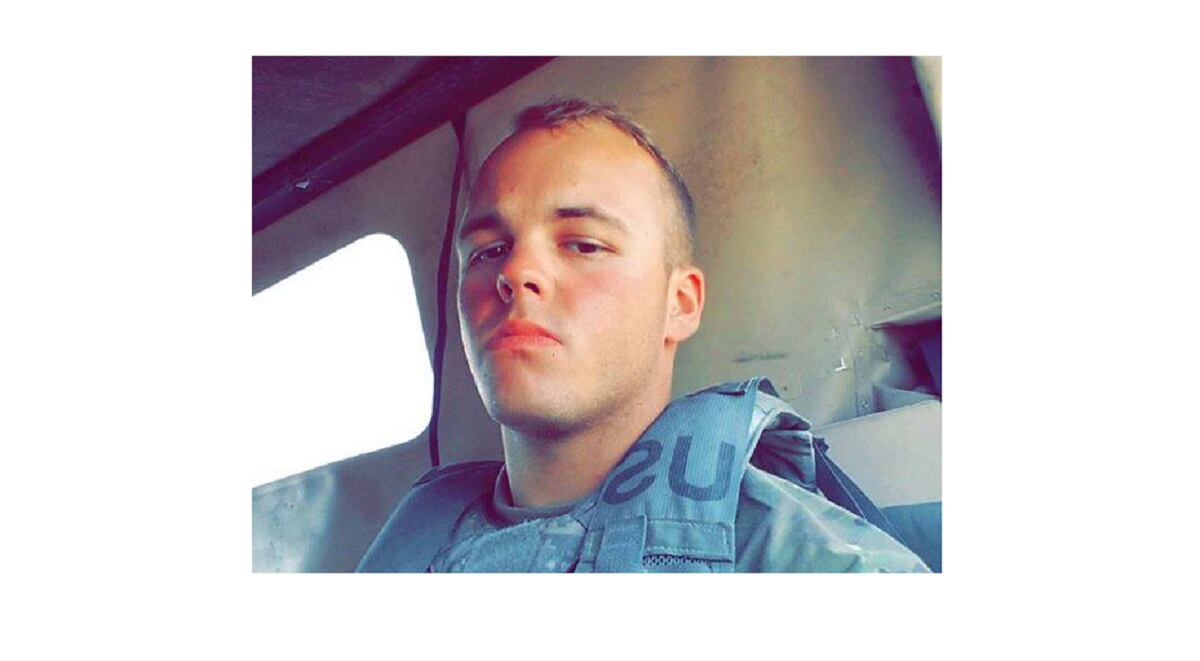

Pvt. Dakota Stump had been assigned to a cavalry troop at Fort Hood, Texas, for about three months when, on Oct. 10, 2016, he went missing during a break from a field training exercise.

His cellphone had pinged a tower in his hometown of Indianapolis, Fort Hood military police told his mother, and he was declared absent-without-leave two days later.

But on Nov. 3, some soldiers setting up an ad hoc land navigation course found a destroyed Ford Mustang in the woods on post, about 100 meters from the nearest road, with a body wearing a uniform resting several feet away.

The soldier’s name tape read “Stump.”

“The whole time he was laying in the woods, and nobody would go look,” Stump’s mother, Patrice Wise, told Army Times after he was found. “He knew going into this that he could be giving his life for all of us, and they couldn’t even go look for him. We were told that we were taking time away from their training.”

A spokesman for Fort Hood said that the soldier’s unit had conducted an exhaustive search.

“Leaders from the 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, began a unit level search for Pfc. Stump as soon as he failed to report to formation on Oct. 10, 2016,” spokesman Christopher Haug told Army Times. “On Oct. 13, 2016, the scope of the search expanded, reaching outside of Texas as a result of additional civilian efforts. The search for Pfc. Stump continued until the day his remains were found on Nov. 3, 2016.”

Haug could not elaborate on the specifics of the installation-wide search, such as whether units had searched near roads that led from Stump’s barracks to his unit’s motor pool, where he was expected the night he disappeared.

Wise is not convinced that her son’s chain of command did everything they could to find him.

“It shows me Fort Hood had no real plan of action to take when dealing with a crisis such as a missing soldier, from what I see in this report, and living through the unorganized efforts of many that only hindered them finding Dakota, while they sent his family in the opposite direction for three weeks and three days,” she told Army Times recently.

A command 15-6 and subsequent criminal investigation — recently obtained by Army Times via a Freedom of Information Act request — found that Stump, who was posthumously promoted to private first class, had died when he missed a turn while speeding on post, flinging his car hundreds of feet into a treeline, killing him as it impacted, flipped and then impacted again.

Stump, a 19-year-old indirect fire infantryman, had been at the tail end of a four-hour refit during a field exercise with A Troop, 4th Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division.

Based on witness statements and his cell phone records, the soldier had driven with two other soldiers to an on-post shoppette around 6:30 p.m., where he withdrew money for one of the over-21 soldiers to buy a bottle of Pinnacle vodka.

They then took the alcohol back to their barracks to drink it. Stump had until 9:50 p.m. to get back to his troop’s motor pool to head back into the field.

According to his text messages, at around 9 p.m., he told his girlfriend he was “drunk as f---.”

“I am unable to determine whether PVT Stump’s girlfriend believed he had been drinking or not, but there are no indications that she either told him to stop or made any other attempt to contact anyone in the unit and let them know that he had been drinking,” the investigating officer wrote in the command report.

Stump was already three minutes late when one of his friends heard tires squealing and saw the private’s Mustang tearing out of the barracks parking lot. Witnesses later saw him run a red light, according to the investigation.

AWOL

When he hadn’t shown up to his unit or responded to phone calls by the next day, his unit reported him missing to Fort Hood’s military police.

Early on in the case, theories flew in every direction.

The young soldier, who had been counseled once for missing a formation, was known as a “good, but average” performer, who spent most of his free time at the gym, with his girlfriend, or with other members of his troop’s mortar section.

“No, never suicidal thoughts or endangering his life, but he would joke around about harming his feet or legs to get out of the Army,” one soldier said when an investigator asked whether Stump had exhibited any worrisome behavior.

But CID found that there had been some warning signs.

“PV2 Stump made a Facebook post about a month and a half ago that he was going to disappear and nobody was going to find him,” according to their investigation.

Over the course of the search, Wise expressed concern to MPs that her son might have taken his own life.

“Sometimes I wish I would have went through with what I [was] going to do 5 years ago,” he wrote in a text message to his girlfriend weeks earlier, disclosing that he had attempted suicide before. “I’m tired, mad, pissed off, wanna kill somebody, wanna kill myself, sexually frustrated, in my feelings, all at the same time lol.”

He also joked about wishing one of his own mortars would blow him up, according to text messages.

But his mother also suspected he had been a victim of foul play.

“We didn’t think Dakota would ever go AWOL or commit suicide or just take off, because he was just going to work,” she told Army Times. “He was very excited about the Army. A lot of people reached out to me and he told us when he was home in September that he was pretty excited about getting into Ranger school.”

Soon after he went missing, she and Stump’s step-brother told a local Texas television station that Stump had been dissatisfied with his experience in the Army so far, thought he was going to see more action, and that he could get out of hand when drinking.

The AWOL theory took off on Oct. 13, when MPs ran a check to see the last place his phone had hit a cell tower. His phone was in Indianapolis, they said.

As it turned out, the soldier who ran the number had copied it down wrong.

“An administrative error caused the military police to believe PVT Stump was in Indianapolis, and reported that information to PVT Stump’s unit,” according to the investigation.

But according to his mother, the unit explained it away by saying that the pinging process is imprecise.

So Wise sprang into action, calling the local police as family and friends searched the city for her son. But the police couldn’t do anything, because Stump was listed as AWOL, putting him in the Army’s jurisdiction.

To help out, his unit re-listed him as a deserter on Oct. 19. Now the Indianapolis police were able to start a search, but once Stump’s body was found, the unit had to quickly change him back to “present for duty” in order for Wise to receive survivor’s benefits.

“They said they get wrong pings sometimes, and the lead investigator explained that his wife could be calling from Virginia but it would show up as in Connecticut,” she said.

That error prompted an internal review at Fort Hood, the spokesman told Army Times.

“Following the Army Regulation 15-6 investigation on the Pfc. Dakota Stump incident, Fort Hood conducted an internal review and changed its procedures for handling cell phone geo-location procedures,” Haug said. “A redundant process has been implemented with confirmation of input by a second individual involved in the investigation.”

RELATED

Since Stump’s death, Wise has made a push to enact a law in her son’s name, which would simplify searches for service members and veterans by allowing tracking information collection without a warrant, conducting an investigation before declaring AWOL status, and activating a “Warrior Alert,” similar to the Amber Alert for missing children.

“Until there are laws and procedures set to be followed, each case can have the same end result,” she said. “You don’t have to do a lot of research to see the death toll at Fort Hood continuously rising, and I believe it’s up to the community as a whole to demand answers and promote change.”

Wise has also retained a forensic expert to go over her son’s autopsy. The doctor agreed with the fatal car accident finding, she said, but added that “major points” of the investigations leave questions he can’t answer.

High risk

Having determined that Stump had died in a single-vehicle accident, CID stepped in to fill in the circumstances surrounding it.

After receiving diagnostics from the recording device in the soldier’s car, investigators were able to recreate the accident.

Stump had been travelling at 62 mph, according to the report, when he missed a sharp left bend in the road and drove straight into the trees, at a 20 percent incline.

There his car hit a dirt mound, went airborne again for about 100 feet, hit the ground again, and launched 50 more feet before hitting a tree stump and rolling another 70 feet before coming to rest on its side.

“His vehicle flipped multiple times before landing on its side more than 200 feet into the woods, “according to the 15-6. “ PVT Stump was thrown from the vehicle, landing 10 feet from the car.”

He wasn’t wearing a seat belt and had apparently died from blunt-force injuries, the report said, and a toxicology screen came back negative.

However, Stump’s body was so decomposed at the time that traces of alcohol would have been difficult to find. The lab used a piece of his calf muscle for the toxicology report, and relied on dental records to make a positive identification of the body.

Investigators also found Stump’s wallet in his pocket, and, during a site visit in late March, found one of his dog tags.

“Pfc. Stump’s death was an unfortunate and tragic accident,” Haug said. “Using the findings of the Army Regulation 15-6 investigation, which is not contradicted by the recent CID investigation, the command continues to review and adjust procedures to increase the safety of our Troopers. Our hearts go out to Pfc. Stump’s family and friends.”

The unit’s investigating officer asked Stump’s fellow soldiers whether he had a drinking problem. One answer was redacted, while another soldier said he didn’t feel Stump’s alcohol consumption was over the top.

“He had no indications of being [a] high risk soldier, but any good leader knows in reality all brand new soldiers, ‘privates’ are high risk,” a former squad leader told the investigating officer.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.