For much of the past two decades, the American public has associated the Army’s special operations forces with counterterrorism, often conjuring images of night-time direct action raids.

But as the Global War on Terror draws down in scope and scale, and as senior Pentagon leaders and White House officials turn their attention towards the next potential conflict — ARSOF is shifting its priorities. Their new mission: Create resistance networks that make invasions by Russia or China too costly for those powers to even attempt.

For many of the Army’s special operators, that means a return to their unconventional warfare roots, which stand in contrast to conventional forces’ own renewed focus on large-scale combat operations.

Army Times reviewed new publications, spoke with forward-deployed leaders and caught up with other SOF officials to provide a look behind the curtain at how the Army’s most elite forces are embracing the new “Resistance Operating Concept.”

Even the Army’s top leaders are signaling their support for the idea.

“We are rethinking our overall strategy for the special operations community,” Army Secretary Christine Wormuth told lawmakers in a June 29 hearing. “I think you’ll see us…putting an emphasis on unconventional warfare.”

“Our special forces are uniquely suited to do that,” said Gen. James McConville, the service’s chief of staff, in agreement with Wormuth.

“We want the Baltics to present a deterrent to Russia. And part of what we can do in the Army is have our special operations forces work with the Baltic militaries to help them in terms of…developing what I would call resistance capabilities,” Wormuth later explained, referring to the small countries on Russia’s western border adjacent to the Baltic Sea. “I think the Baltics can do that relatively inexpensively, but they would benefit quite a bit from our expertise and deep [unconventional warfare] knowledge base with our special forces.”

What is the ROC?

The Resistance Operating Concept centers around building up the capacity of friendly countries to mount an effective civil and military resistance if they were to face invasion and occupation from a hostile great power, such as Russia or China.

The ROC is “a planning guide” for the U.S. and potentially vulnerable partner nations that ensures “each side speaks the same [operational] language, and they can go ahead and plan together for resistance,” according to its primary author, Dr. Otto Fiala, who explained it in a July podcast released by 1st Special Forces Command.

Fiala, who is also a retired Army Reserve civil affairs officer, led the drive to codify the ROC while working at Special Operations Command-Europe.

The published book-length version of the ROC is available online through Joint Special Operations University.

The ROC “bridge[s] the understanding between unconventional warfare and resistance,” he said.

Nations supported under the ROC are encouraged to establish the legal and organizational framework for a resistance and bring it under the official control of their armed forces. One such example is the Estonian Defence League, a volunteer paramilitary organization whose 16,000 members are organized under Tallinn’s defense ministry and receive training from U.S. special operations.

Resistance movements — especially when coordinated and organized under the authority of a county’s legitimate government — have historically made it difficult for invading forces to consolidate and secure their gains. And U.S. forces have supported such efforts in the past.

The French Resistance from World War II, which features as a case study in Fiala’s book-length ROC, inflicted casualties and sabotage on occupying Nazi forces for years. Their network also played a pivotal role in enabling the successful D-Day invasion of Northern France in 1944. These efforts, though, took years to organize and bring under coordinated control.

U.S. and NATO forces also conducted clandestine preparations for “stay-behind” guerilla networks across Western Europe, such as Italy’s Operation Gladio, in the event of Soviet invasion and occupation. But those efforts trained and empowered right-wing paramilitaries, critics said, and their clandestine nature resulted in politically-explosive public revelations during the 1990s.

The key lessons from these scenarios, according to Fiala and other SOF thought leaders, is the need to coordinate and prepare for such resistance movements ahead of time — unlike WWII France — while also working within the legal frameworks of partner nations to provide public-facing preparatory support, unlike secretive Cold War-era “stay-behind” efforts.

Focusing on building resistance capabilities allows the nations to “put their own face on their national defense,” said Master Sgt. Frank Miller, a decorated Green Beret and Army Special Operations Command staffer, on the podcast. “They’re not a puppet — their defense is that country’s defense, and we’re just assisting with their own project.”

One experienced civil affairs officer, Lt. Col. Matt Quinn, described the role of SOF in competition and resistance preparation as a Venn diagram.

“One circle is U.S. military objectives, and the other circle is U.S. [diplomatic] objectives, and the last circle is the host nation objectives,” Quinn, commander of the Europe-focused 92nd Civil Affairs Battalion, said in a phone interview.

“And then where they overlap,” he added, “that’s where we operate.”

Frozen conflicts

When it comes to the national objectives of countries in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus region, the threat of invasion and occupation isn’t just real — it’s their lived reality.

Russia sponsors a number of so-called “frozen-conflicts” in post-Soviet states where pro-Moscow separatists have managed to hold off the legitimate government thanks to support from Russia. Moscow’s troops currently occupy territory internationally recognized as belonging to Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia.

The reality of the Russian threat makes many of those nations — and other Western-aligned states in the region — eager to develop a “total defense” strategy, to include planning in advance for resistance.

“Twenty percent of [Georgia] is currently occupied by Russia, and the people here are very cognizant of that,” a Green Beret officer told Army Times on background during Agile Spirit 21, a recent exercise that included a resistance-driven special operations training scenario. “This concept of total defense is not new to Georgia, and they’re very proud to embody it.”

Setting the conditions for total defense and resistance requires gaining and maintaining the support of the civilian population by “inoculat[ing] and hardening” them against enemy disinformation, 4th Psychological Operations Group commander Col. Christopher Stangle told Army Times.

RELATED

Senior ARSOF officials in the Pacific theater also see building resistance capability as a key component of countering rising Chinese influence in the region.

“Our allies and partners here in the [Pacific] are in this conflict space [with China] right now,” said Lt. Col. Erik Davis, commander of 1st Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group, which is stationed in Okinawa, Japan. “They’re having to assert their sovereignty and reassert their sovereignty as China pushes everywhere it can in the South China Sea and the East China Sea.”

The ROC doesn’t yet have the same influence over Special Operations Command-Pacific’s exercise schedule as in Europe. But one of the command’s planners, Lt. Col. Ron Garberson, said they’ve been collaborating with their Europe-based colleagues for “quite a few years” to implement aspects of the approach.

To that end, SOCPAC hosted a formal working group in February 2020 to discuss potential uses for resilience and resistance planning in upholding sovereignty for partner nations in the Indo-Pacific.

Fiala, the ROC’s author, said effective preparations for resistance and total defense can help prevent the next war.

“It’s difficult to measure deterrence,” he said in the podcast. “But an adversary knowing that you have this resistance capability, there is an organization that exists [to execute resistance], and that your people are willing to resist is a strong message of deterrence.”

“It has to do with their commitment to their own sovereignty and survival as a nation,” he said. “Putting together an organization and being willing to resist is their up-front commitment, which makes it much easier for [the U.S.] to support long-term.”

The Green Beret officer in Georgia put it succinctly — “The whole point of this is that you hopefully never have to use it.”

Training and preparing

In recent months, U.S. forces have placed new emphasis on training would-be resistance organizations as the ROC is implemented across much of Europe.

Initially, implementation of the ROC began with tabletop exercises and wargames focused on Nordic and Baltic states, which have a strong resistance tradition stretching back to the Soviet occupation after World War II. But the concept has since expanded to other parts of Special Operations Command-Europe’s area of responsibility and stepped from the tabletop into the field.

An ARSOF cross-functional team featuring special forces, civil affairs and psychological operations troops embedded with Georgian special operations forces for a week-long resistance training scenario in August as part of Agile Spirit 21.

“The SOF aspect of the exercise [was] anchored on the resistance operating concept,” a second SOCEUR official told Army Times on background in order to freely discuss the exercise. “So the concepts that go within the ROC are being trained and stressed by SOCEUR.”

Polish, British and Romanian special operations troops also participated in the SOF portion of the multinational exercise.

The event marked the first-ever special operations exercise hosted by Georgia while “work is ongoing” in Tbilisi to establish the legal and organizational framework for a resistance-driven total defense strategy, according to the Green Beret officer who represented SOCEUR at the exercise.

During the training event, special operations troops practiced providing support to a notional Georgian resistance movement “to prevent the occupying enemy from consolidating their gains within the recently occupied territory,” the Green Beret officer said.

“A lot of the scenario skillsets center around the basic infantry tasks, but doing them on a consistent, professional basis,” the second SOCEUR official said. “Within the exercise, you see stuff like interdiction scenarios, ambush scenarios [and] personnel recovery scenarios.”

“It’s also doing things like sabotage,” said the Green Beret. “The focus is doing [these tasks] with and through an attached partner force.”

Other exercises in recent years have included similar invasion and resistance scenarios.

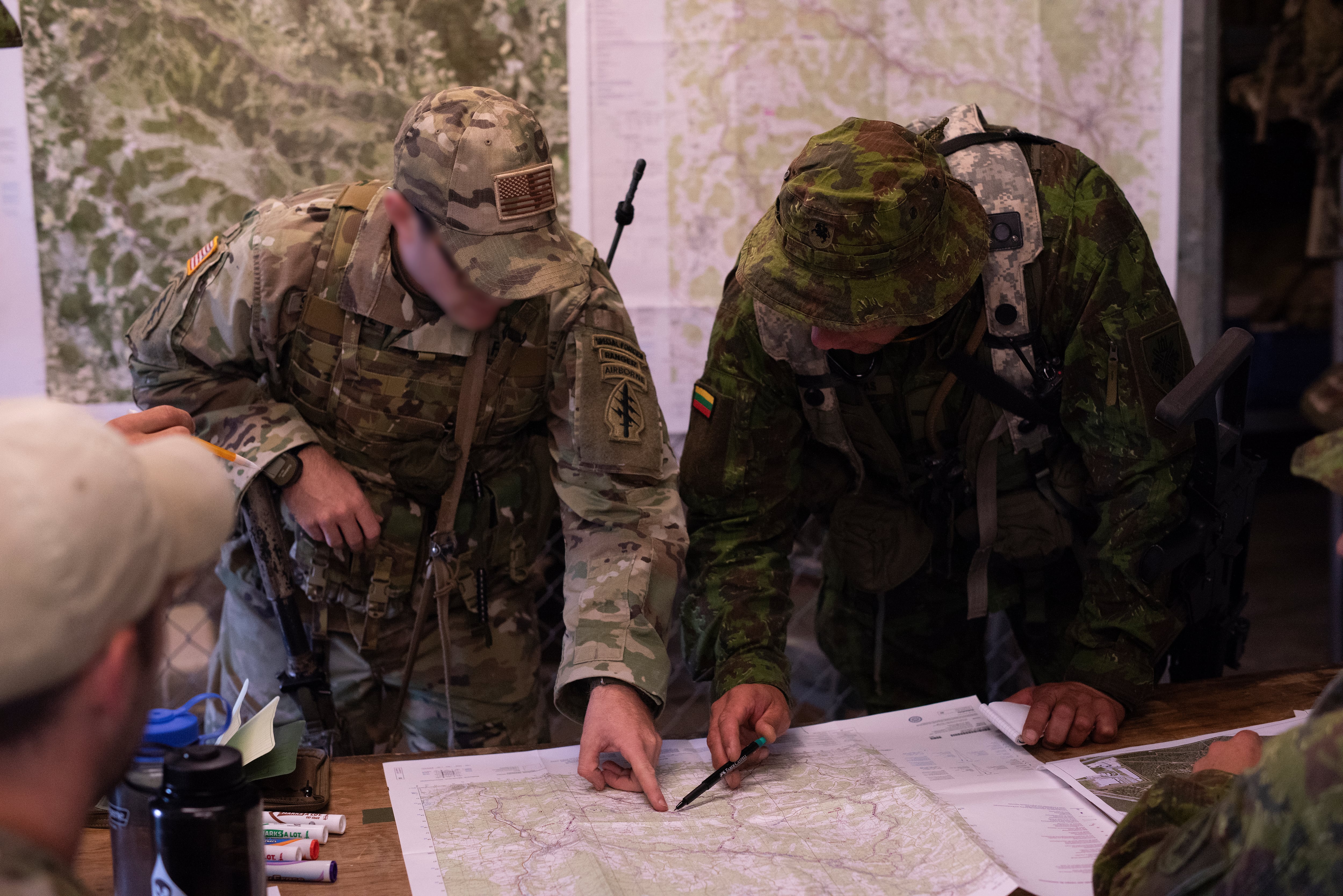

U.S. Army Europe’s Saber Junction exercises frequently rehearse such concepts, including 2018 and 2020 iterations where members of the Lithuanian National Defense Volunteer Forces partnered with Green Berets to conduct irregular warfare behind enemy lines.

The 2018 version of the Trojan Footprint exercise had NATO special operations forces enter notionally-occupied territory. There, they linked up with SOF troops from the Baltic states “to assist with their defensive capabilities, such as working with organizations like the Estonian Defense League, Latvian National Guard and the Lithuanian National Defense Forces,” according to a SOCEUR release.

Hearts and minds

While tabletop exercises and training events play a key role in preparing for a resistance scenario, civil affairs and psychological operations soldiers play a large part, too.

Quinn, the Europe-focused civil affairs commander, said that his teams across the continent are doing many of the same things he did when forward-deployed during the height of the Global War on Terror.

“When I was a company commander, the focus was countering violent extremism,” he told Army Times. “The objectives laid out by higher headquarters — [they’ve] been adjusted. ... However, the way we do business from a tactical and operational perspective is very similar.”

Quinn says civil affairs assets can help strengthen the bonds and coordination between the government, security forces, volunteer resistance organizations and other nodes of community organization ahead of a resistance scenario.

“Very often, civil affairs is a matter of herding cats,” said Fiala. “It’s bringing different groups together and getting them to understand their roles.”

The battalion commander also described how the relationships and networks built through the “persistent presence” of civil affairs teams can help to counter the influence of hostile actors, especially among vulnerable populations affected by the specter of unresolved frozen conflicts.

In one European country, he explained, the civil affairs team was able to implement “civilian perspective” resistance-oriented exercises that focused on the civil resistance of non-military actors.

“The majority [of resistance] is non-violent,” Quinn noted. “The population is already the primary actor — or at least a significant actor — in the whole-of-society approach. … From the civil affairs perspective, a lot of the activities and engagement are very non-lethal.”

Psychological operations soldiers see preparing for the resistance mission in the same way.

Stangle, the 4th Psychological Operations Group commander, explained that it’s “largely about building the partnerships within the countries abroad that enable those host nations to either be resilient or inoculated to be resistant against foreign adversary efforts.”

Those initiatives look different in different parts of the world, Stangle said.

“Depending on where we are, we may be helping a foreign [partner] government legitimize their activity…[or] we may be attempting to…enable them to push back against adversary mis- or disinformation,” he said. “We’re not so much focused on selling [U.S. government] narratives as we are legitimacy, open transparency with democracy [and] open freedom of the press.”

“Our preference,” he said, is to “teach our foreign partners to lean forward and to be aggressive in their narrative.”

“Being responsive [to adversary disinformation] is always difficult,” he added. “You have to visualize what the adversary is going to use against you, and then undermine those negatives up front and take away those argument[s] early on so that they can’t be used against you.”

Fiala also mentioned the central role of messaging the ROC in the podcast.

“Do [partner nations] have their narratives ready to go to dominate the information environment immediately if an adversary starts giving indications and warning [of invasion]?” he asked.

“There are narratives that you do now, in order to go ahead and put out the message that you’re willing to resist, that you are a resilient society, and then you have your [information warfare] stack ready to go in case problems come out,” he added.

If conflict breaks out, psychological operations forces would transition to a “very aggressive” direct messaging approach, Stangle explained.

That’s also where deception operations intended to facilitate the resistance would come into play.

Another aspect of sustaining resistance through psychological operations is getting the message into occupied areas, he added.

“We would look at how we bring hope, sustain their efforts, and promote additional partisan or resistance efforts on their part,” Stangle said.

Ultimately, Army special operations planners have argued, the goal is to establish “unconventional deterrence,” discouraging an enemy from invasion and occupation.

This creates a “bitter pill” for the enemy to swallow in the form of a well-organized, effective resistance movement.

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.