Fans of the baseball tear-jerker, “Field of Dreams,” starring Kevin Costner and James Earl Jones, are quite familiar with the mystique surrounding Archibald Graham, portrayed in the film during his later years by legendary actor, Burt Lancaster.

As the story goes, Graham had been toiling in the minor leagues for a number of years when, in 1905, his dreams of playing at the game’s highest level were finally realized after the New York Giants purchased his contract.

During the waning moments of a game that year, Graham was summoned from the bench, for the first time, to replace George Browne in right field. With his team up to bat and two outs in the top of the ninth inning Graham strode into the on-deck circle, confidently awaiting a chance to hit in the big leagues for the first time. But Claude Elliot flied out. The game was over.

Graham never played in another Major League game.

Almost 34 years after “Doc” Graham — as he was affectionately called in his Chisholm, Minnesota, neighborhood where he practiced medicine for 50 years after walking away from baseball — made his only appearance in a Major League game, another player was writing a similar script, except his was not a story magnified in a book or immortalized through cinema.

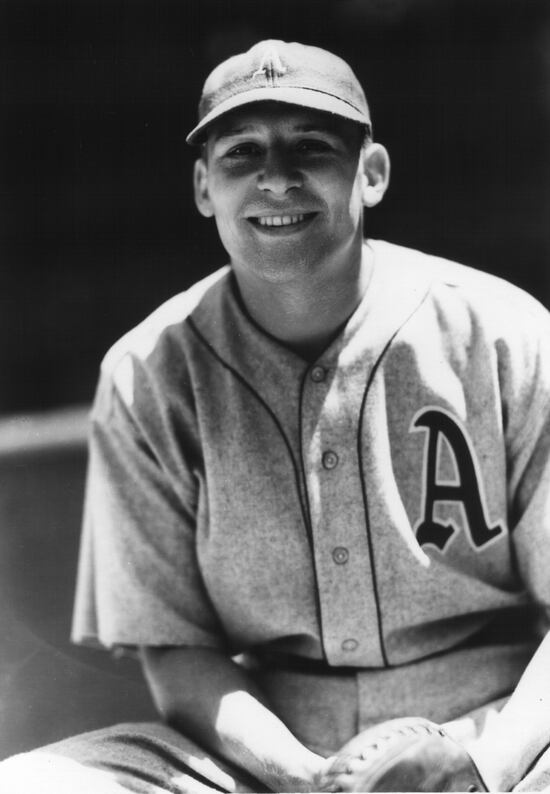

Harry O’Neill was a highly-touted three-sport athlete coming out of Gettysburg College in 1939. On the day of his graduation, the Philadelphia Athletics — and Hall-of-Fame manager, Connie Mack — came calling, inking the 6-foot-3, 205-pound star catcher to a contract that paid him $200 a month.

O’Neill would spend that season as the team’s third-string backstop, a role that relegated to him to warming up pitchers in the bullpen while never sniffing the prospect of Major League action.

Then, in the eighth inning of a July 23, 1939, game between the A’s and Hank Greenberg’s Detroit Tigers, O’Neill’s restriction to the pen was lifted.

After entering the game as a defensive substitute, O’Neill, like Graham, would spent the next two innings without being afforded the chance to dig his cleats into the pristine dirt of a Major League Baseball batter’s box.

Detroit would go on to bludgeon the A’s by a score of 16-3, and Harry O’Neill would never again be called into a Major League game.

But unlike Graham’s universally respected leap into the world of medicine, O’Neill’s life after baseball would take him to distant corners of the world — to islands most Americans at the time had never heard of.

O’Neill was bouncing between high school coaching gigs, playing semi-professional basketball and football, and making last-ditch attempts at clawing his way back into Major League Baseball when the Japanese stunned the world by launching a vicious attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Like many Americans, O’Neill responded by volunteering to fight. Within a year of the attack, he was wrapping up Marine Corps basic training, donning the Eagle, Globe and Anchor and heading off to Quantico, Virginia, to become an officer.

Upon pinning on the brass insignia of a Marine second lieutenant, Harry O’Neill received orders to Camp Pendleton, California, to train with the recently-formed Fourth Marine Division.

At Pendleton, O’Neill’s knack for leadership quickly turned the heads of his superiors, earning him a promotion to first lieutenant.

Things in his personal life were also going well.

O’Neill was newly married to his hometown sweetheart, Ethel McKay, who made the cross-country trip to California from Colwyn, Pennsylvania, to spend what little time the couple had together before a ever-looming deployment to the Pacific interrupted any semblance of a normal matrimony.

And brief her visit was.

On Jan. 13, 1944, 1st Lt. Harry O’Neill and the Marines of the 25th Marine Regiment, Fourth Marine Division, loaded their gear onto ships and steamed for a relentless enemy awaiting them across a vast ocean.

ISLAND HOPPING

It wouldn’t be long after departing California before the young Marine experienced his first taste of action.

Less than three weeks after kissing his wife goodbye, O’Neill waded ashore on the 880-yard-wide, two-and-a-half-mile-long island of Kwajalein as part of an amphibious assault by Marines who made quick work of fortified Japanese defenses.

The island was declared secure in only four days, marking a significant momentum shift for U.S. forces in the island hopping campaign toward mainland Japan.

By June 1944, O’Neill and the Marines from the “Fighting Fourth” had their sights set on their next major target: Saipan.

Just one day after landing on the beach and beginning the push inland O’Neill would be hit in the arm by shrapnel from an artillery round, an injury that sidelined him for weeks on a hospital ship while U.S. forces inflicted nearly 30,000 casualties on Japanese defenses.

Thousands of Japanese civilians would also die in the nearly four-week assault, many by their own hand.

Sufficiently healed, O’Neill rejoined his unit on July 22, just days before another successful assault by the Fourth Marine Division — this time on the island of Tinian, a week-long campaign that netted the U.S. and its allies an airfield that would become one of the most heavily used throughout the rest of the war.

IWO JIMA

Months after their success at Tinian, the Fighting Fourth were tasked with a fourth major assault just over a year. Their new objective was a small, volcanic island with black beaches and rough, ragged terrain.

One Navy lieutenant, while viewing the island from the bridge of a troopship, described the land mass as “a rude, ugly sight,” according to a WWII commemorative series by the National Park Service.

“Only a geologist could look at it and not be repelled.”

At 6:45 a.m. on Feb. 19, 1945, the order was given to launch the assault on Iwo Jima.

A thunderous naval and aerial bombardment commenced, pummeling targets that had long been identified on maps during planning stages.

Anxious Marines, including Harry O’Neill and men from the 25th Marine Regiment, looked on in awe from their Higgins boats as orange bursts of hot steel tore at the hellish, volcanic landscape, clouding the air with impenetrable smoke.

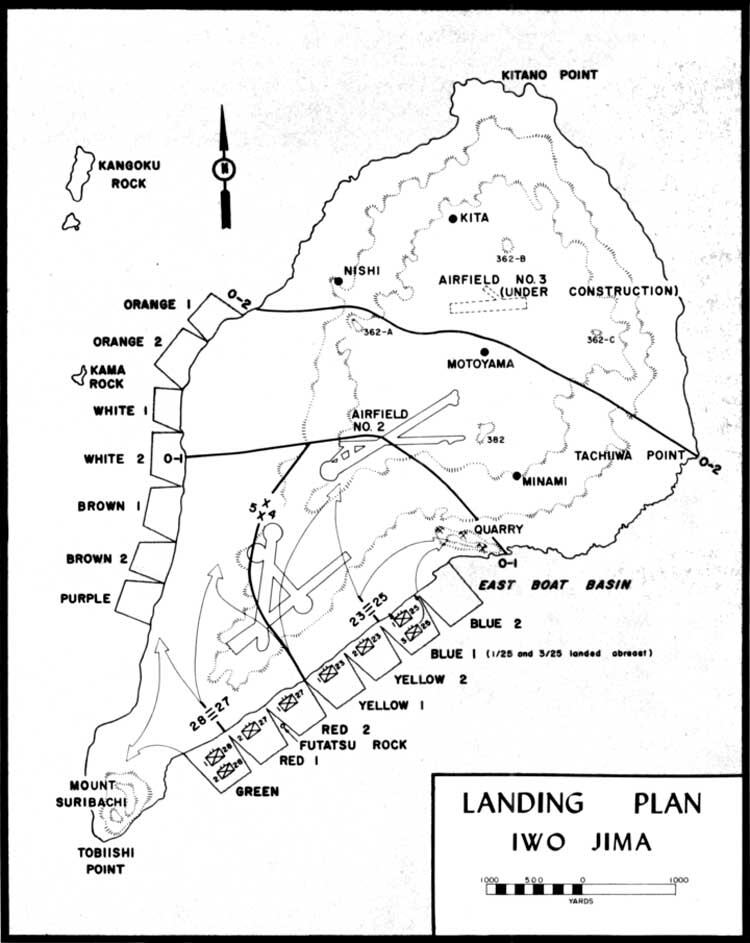

The 25th were given the daunting task of assaulting Blue Beach Two and scaling a towering area known as the Rock Quarry, a vulnerable sector along the extreme right flank of the attack that was in full view of elevated Japanese fortifications.

So ominous was the assignment that Maj. Gen. Clifton B. Cates, commander of the Fourth Marine Division, remarked, “If I knew the name of the man on the extreme right of the right-hand squad I’d recommend him for a medal before we go in.”

By 9 a.m. Marines and landing craft from other divisions covered much of the beach, yet to encounter the barbarous resistance that awaited as the day wore on.

For many, the terrain itself posed the first obstacle. One Marine recalled the sand being “so soft it was like trying to run in loose coffee grounds.”

Advancing up Blue Beach, meanwhile, the 25th Marines saw the object of Maj. Gen. Cates apprehension come to fruition. A withering, concentrated barrage of rifles, machine guns, mortars and artillery greeted the advancing Harry O’Neill and his men.

“That right flank was a bitch if there ever was one,” Cates recounted.

Unforgiving topography made finding cover from the relentless onslaught nearly impossible. One Marine compared trying to dig a fox hole to carving out "a hole in a barrel of wheat.”

A 10:36 a.m. message over the command net from the battered 25th Marines to the assault’s flagship painted a grim picture of their prospects.

“Catching all hell from the quarry,” the correspondence said. “Heavy mortar and machine gun fire!”

Lt. Col. Justice Chambers, who would receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on Iwo, recounted the near-impossible task of scaling the Rock Quarry’s steep, treacherous incline under a hailstorm of enemy ordnance.

“Crossing that second terrace, you could’ve held up a cigarette and lit it on the stuff going by,” he said. “I knew immediately we were in for one hell of a time.”

Marines on the other side of the island, meanwhile, had taken Mount Suribachi, raising a replacement American Flag — after the original was taken down — on Feb. 23, a moment made iconic by photographer Joe Rosenthal.

A little over a week later, the first damaged U.S. B-29 bomber returning from a raid on Tokyo was able to land safely on Iwo Jima’s Airfield No. 1.

The Marines were making headway, but fighting remained.

For O’Neill and the 25th Marines, territorial gains through the Rock Quarry and the Turkey Knob — a section of the island referred to ominously as “The Meatgrinder” and one critical to securing the second airfield — were much harder to come by.

On March 6, O’Neill found himself in a vicious, day-long fight in The Meatgrinder when he managed to find what he perceived as decent cover — a bomb crater he climbed into with Pfc. James Kontes.

“We were standing shoulder to shoulder. Harry was on my left," Kontes said in a 2009 interview with the Bucks County Courier Times. "We were looking out at the terrain in front of us. And this shot came out of nowhere.”

Kontes watched his lieutenant collapse. The sniper’s surgical round tore into O’Neill’s neck and severed his spinal cord. He was dead before he hit the ground.

Harry O’Neill was 27 years old.

AFTERMATH

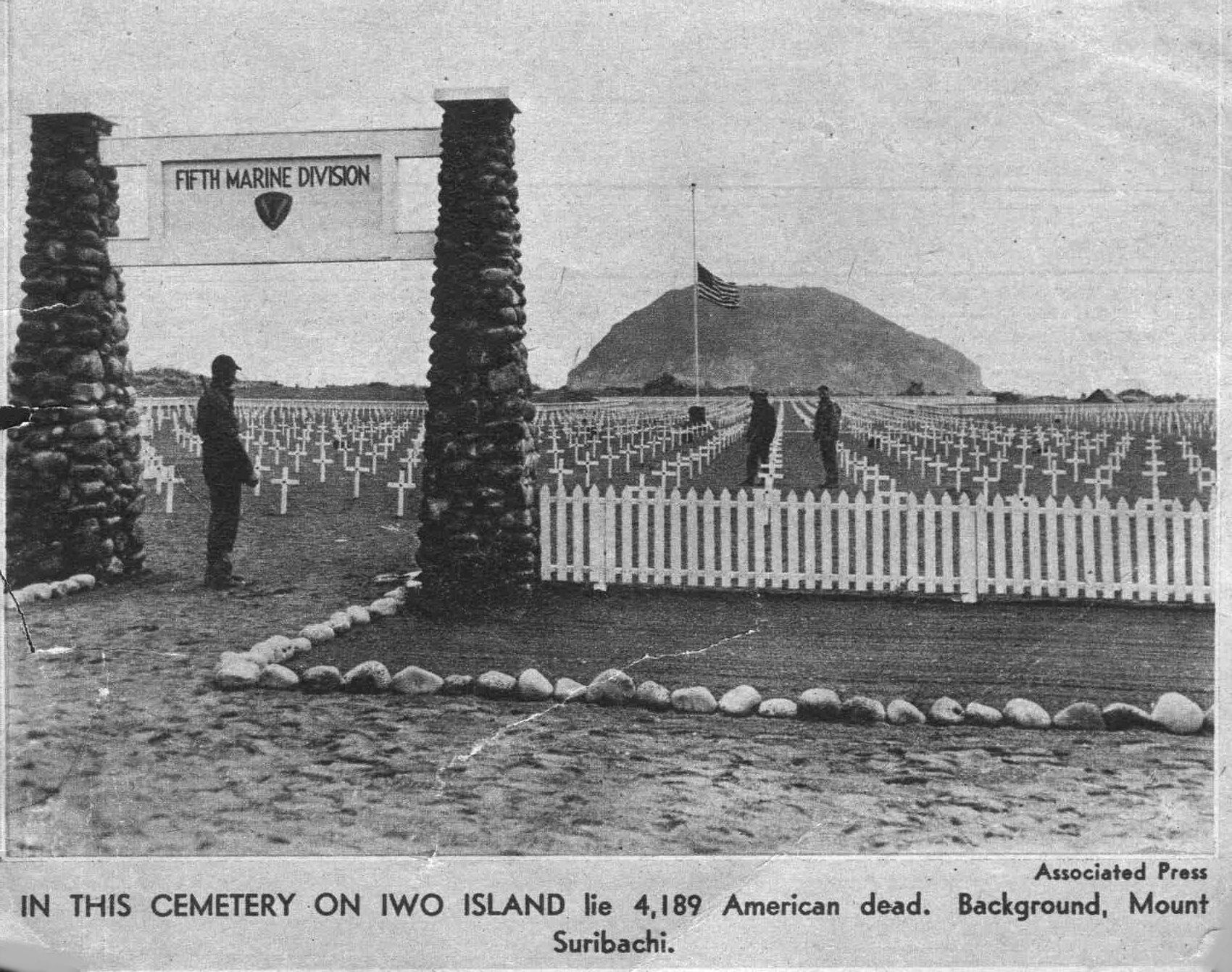

It would be another 20 days before the Marines declared Iwo Jima secure.

O’Neill, along with nearly 7,000 other Marines, was buried in the island’s vast cemetery, Mt. Suribachi looming ever-present over the seemingly endless rows of headstones.

Two years elapsed before O’Neill’s body was returned to the United States and laid to rest in Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania.

In all, over 1,800 Marines from the 4th Marine Division were killed on Iwo Jima. Another 7,200 were wounded. The total number of casualties incurred by the Fighting Fourth accounted for more than 50 percent of the division’s total force.

“At Tarawa, Saipan, and Tinian, I saw Marines killed and wounded in a shocking manner, but I saw nothing like the ghastliness that hung over the Iwo beachhead,” recalled Marine and combat correspondent, Lt. Cyril Zurlinden.

“Nothing any of us had ever known could compare with the utter anguish, frustration, and constant inner battle to maintain some semblance of sanity.”

News of Harry’s passing would not reach Ethel until April.

In death, O’Neill was immortalized, becoming one of just two players with Major League Baseball experience to be killed during World War II.

The other, Elmer Gedeon, was killed in 1944 when a B-26 bomber he was piloting was shot down over France.

Shortly after news of Harry’s death reached his family, O’Neill’s sister, Susanna, wrote a letter to Gettysburg College, disclosing the tragic story to the coaches and faculty of the athletic department where Harry had wowed so many as a three-sport star just a few years earlier.

“We are trying to keep our courage up, as Harry would want us to do," she wrote. "But our hearts are very sad, and as the days go on it seems to be getting worse. Harry was always so full of life that it seems hard to think he is gone.

“But God knows best, and perhaps someday we will understand why all this sacrifice of so many fine young men.”

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.