A joint research effort between the U.S. Army and the University of Pennsylvania is hoping to train dogs to develop pinpoint detection of COVID-19 biomarkers in humans.

Researchers from the university previously trained dogs to successfully detect both diabetes and ovarian cancer. Given present circumstances, shifting focus to the coronavirus was a no-brainer.

“I called up the research partner in my branch who I work most closely with on dogs,” Michele Maughan, a researcher at the Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center, said in a release. “And said to her, ‘We keep saying we need to find a way for dogs to detect COVID-19, let’s do this!”

Maughan then reached out to the director of Penn Vet’s Working Dog Center, Cynthia Otto, who quickly endorsed the partnership. An additional phone call to Patrick Nolan, a U.S. Army Special Forces veteran and former military working dog trainer, got the ball rolling, and by May 26, just months after proposing the idea, the first dogs entered training.

Nolan, who now owns a training center for working dogs in Maryland, enthusiastically supplied 10 working dogs to participate in the six- to nine-week program.

“Training dogs to do this kind of work, detecting a substance down to the parts per trillion level is an art,” Maughan said in the release. “And I could think of no one better than him to do it.”

Each Labrador retriever in training learns how to detect the proteins the human immune system produces while fighting COVID-19 without ever needing to be exposed to the actual virus.

Because dogs can detect the immune system’s response even before the onset of a fever, they are able to identify COVID-19 carriers without the need of a thermal camera and they’re faster than any swab test.

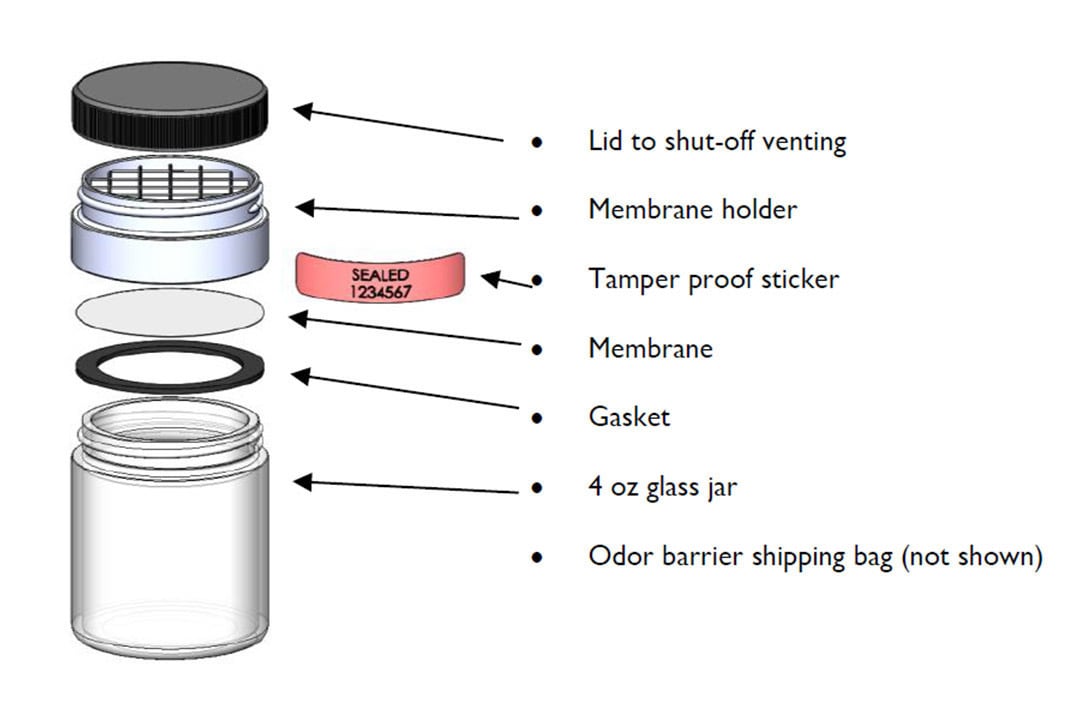

To train the Labs, researchers use a container known as a Training Aid Delivery Device, or TADD, a tightly sealed capsule capable of holding hazardous substances that can be detected safely by each dog.

These devices are then placed on a training wheel containing a series of spokes, or arms, each with a TADD attached to the end. The dog must discern canisters on the wheel that contain substances emitted by a COVID-19 carrier from those containing materials designed to distract the animal, such as food or a toy.

Still, detection isn’t the sole element of training the dogs will have to master. Keeping them locked in on the task at hand for hours at a time is another undertaking entirely, said Jenna Gadberry, Maughan’s research partner.

“Not every dog can stick with the length and degree of intensity of the training to get all the way to being able to detect in the part per trillion range,” Gadberry said in the release.

“And not every dog has the drive to stay with the game for hours at a time, which is essential if the dogs are to provide COVID-19 screening at the entrances to crowded public places such as at airports, sports stadiums, or at border control checkpoints.”

While the end goal is to have dogs assisting such locations, funding for the current partnership extends only through the training itself — not the onsite application of the newly-trained animals.

Despite the program’s future uncertainty, it’d be hard to validate a penny-pinching approach with a cohort of virus-detecting dogs standing by.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.

Tags:

military working dogmilitary working dog covidcovid dog detectiondogs detecting covidcovid-19 dogsbomb sniffing dogs covidcovid impact on animalsIn Other News