It has become one of the most enduring photographs of the Vietnam War: Several wounded, dead or dying American troops ride atop a tank being used as a makeshift ambulance. In the foreground, a corpsman holds aloft an IV drip for a fellow Marine who clings to life with a chest wound.

It is this very photo that has sparked a heartfelt reunion — and a controversy of mistaken identity.

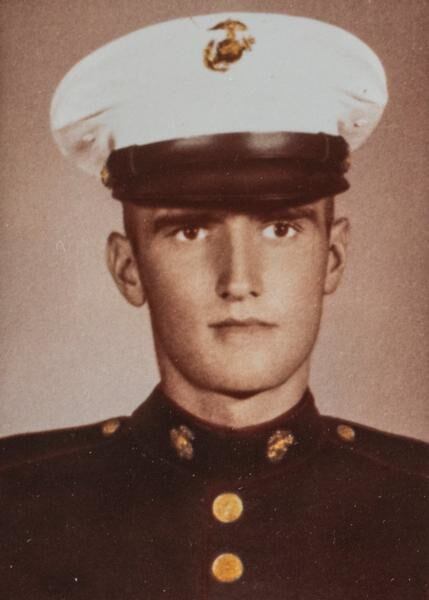

In 2017, author Mark Bowden released his critically acclaimed book, “Hué 1968: A Turning Point of the American War in Vietnam.” Under the iconic photograph, Bowden’s caption identified the injured Marine as Pfc. Alvin Grantham.

The following year, Mayer Katz, who had been a U.S. Army surgeon with a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital unit near Hué, was reading Bowden’s book when he came across the image.

The name in the caption froze him.

“The retired doctor living in Rehoboth Beach, Del., rummaged through old files and found what he was looking for: a logbook of surgeries with the 22nd Surgical Hospital in Phu Bai, a U.S. air base near Hué. There, under Feb. 17, 1968, the same date displayed in the photo caption, were the medical details of Grantham’s operation,” The Washington Post reported.

Katz managed to find Grantham that year, prompting a physical reunion in 2022 and an enduring friendship.

“I got to see him for a 54-year follow-up for surgery,” Grantham told The Post. “Dr. Katz said it turned out well.”

Their first meeting, however, went somewhat differently.

At 3:40 a.m. on January 31, 1968, the city of Hué came under attack. Tet Offensive was in full swing as tens of thousands of North Vietnamese Army regulars and Viet Cong guerrillas poured over the border in an aggressive bid to claim South Vietnam.

Before the day was over, five of six autonomous cities, 36 of 44 provincial capitals and 64 of 245 district capitals had been attacked, according to military historian David Zabecki.

Among those fighting to stop the northern incursion was the 18-year-old machine gunner, Grantham. On the February day described in the iconic photo’s caption, his five-man unit had been decimated after shrapnel from a rocket-propelled grenade wounded all but the ammo humper. Taking over as gunner, Grantham ran into a nearby building to support another squad of Marines under fire.

While returning fire with his M60 machine gun, he became exposed, and North Vietnamese soldiers pinned him down with AK-47 rounds.

Grantham managed to duck several before a bullet sliced through his left lung — barely missing his heart — and exited through his right shoulder. The sucking wound soon made it nearly impossible for Grantham to catch his breath.

“It felt like someone had taken a red-hot poker out of the fire and stuck it through my chest,” Grantham told The Post. “I didn’t think I was going to make it.”

Fellow Marines plugged placed Grantham on a door that another Marine had kicked down for use as a stretcher, plugged his bullet wounds with cellophane from cigarette packs and wrapped him in bandages, according to The Post.

It was there that the gravely wounded Grantham was placed on an M48 tank, and his photo — snapped in the heat of battle by Stars and Stripes photographer John Olson — was taken.

Olson, also a freelancer for Life magazine, found that his striking image ran less than a month later, in the March 8, 1968 issue. The image itself, taken during the brutal battle for the city of Hué, came to symbolize the futility and brutality of the Vietnam War in the eyes of the American public.

Photographer Doesn’t Recall Taking Photo

Although he was awarded the Robert Capa Gold Medal for his work in Hué, Olson has no recollection of the men in the photo — or even taking it, for that matter.

“I remember the tank, I remember the lens I shot it with, but I don’t remember taking the photo,” Olson told The Post. “I have very little memory of that moment. It was all a blur.”

Nine of the Marines on the tank were later identified, but the identity of the Marine with the chest wound continued to elude Olson as well as historians.

“A lot of people have contacted me over the years,” Olson told The New York Times. “But I would ask a series of questions, and the stories would fall apart.”

After hearing from Grantham in 2016, Olson knew something was different. This time, the story, and the records, checked out. On Feb. 17, after being loaded onto the M48, the 18-year-old Marine reached the 22nd Surgical Hospital in Phu Bai, where then-Capt. Katz immediately began surgery to remove the top of Grantham’s right lung as well as bone fragments from two ribs that had been shattered by the enemy bullet.

Grantham’s survival, and his 2018 reconnect with Katz, became, according to The New York Times, an “example of resilience and good luck, and of young Marines saving their own.”

The recognition didn’t end after the two men met.

“In January 2018, the Newseum opened an exhibit, ‘The Marines and Tet: The Battle That Changed the Vietnam War,’ based largely on Bowden’s book and Olson’s photos and research,” the Times wrote. “The exhibit, which has been extended to run through March 17, presents audio interviews with veterans of Hue, including an interview with Grantham that accompanies a large reproduction of Olson’s image. Grantham’s story, Olson’s photo and Bowden’s book were prominently featured in public events and other coverage marking the 50th anniversary, including in Vanity Fair, The Washington Post, on ‘CBS Sunday Morning’ and in many local news outlets.”

Identification ‘Made Me a Bit Ill’

Strong evidence has since come to light, however, that the wounded Marine was in fact not Grantham, but Pfc. James Blaine, an 18-year-old Marine who later died from his wounds.

For Blaine, there would be no Hollywood ending, according to a 2019 New York Times investigation. His identity was uncovered by Anthony Loyd, a British author and long-serving war correspondent for The Times of London who was doing his own research on Marines fighting in Hué.

The misidentification, as Loyd put it, was “like his soul got carelessly mislaid.”

“It made me a bit ill,” Blaine’s brother, Rob, told The Times of London, “thinking that someone had tried to steal this ‘moment’ from my brother, a dead war hero. In my research, I came to believe that Alvin Grantham is an honorable man who had a similar experience as my brother, but his experience was not caught on film by John Olson on that February day in 1968.”

Working with another well-known photographer of the Vietnam War, Don McCullin, Loyd pieced together previously unpublished photographs of the sequence of events leading up to the shot of the tank.

McCullin, who had been present for the evacuation, had documented the entire scene and remembered it vividly. The photographer snapped 30 images, many with clear views of both Blaine’s face and the location of his wounds. The linchpin, however, was the presence of Richard Schlagel in several of the frames. Schlagel “wore a distinctive rubber octopus tucked into his helmet band, which was visible in several of McCullin’s photographs and also in the one shot by Olson,” writes The Times.

Officially, the U.S. Marine Corps identifies the wounded man in the photo as Blaine. In a 2018 paperback edition to his book on Hué, Bowden wrote a postscript, acknowledging Loyd’s case, but concludes “I have left my version the same.”

Regardless, Olson and Grantham remain convinced that it was Grantham lying wounded on the tank that day, and the iconic photo has led to an improbable friendship.

“When I saw A.B., I ran up and hugged him,” Katz told The Post. “We couldn’t stop talking.”

“I thanked him many, many times,” Grantham added.

This story originally appeared on HistoryNet.com.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.