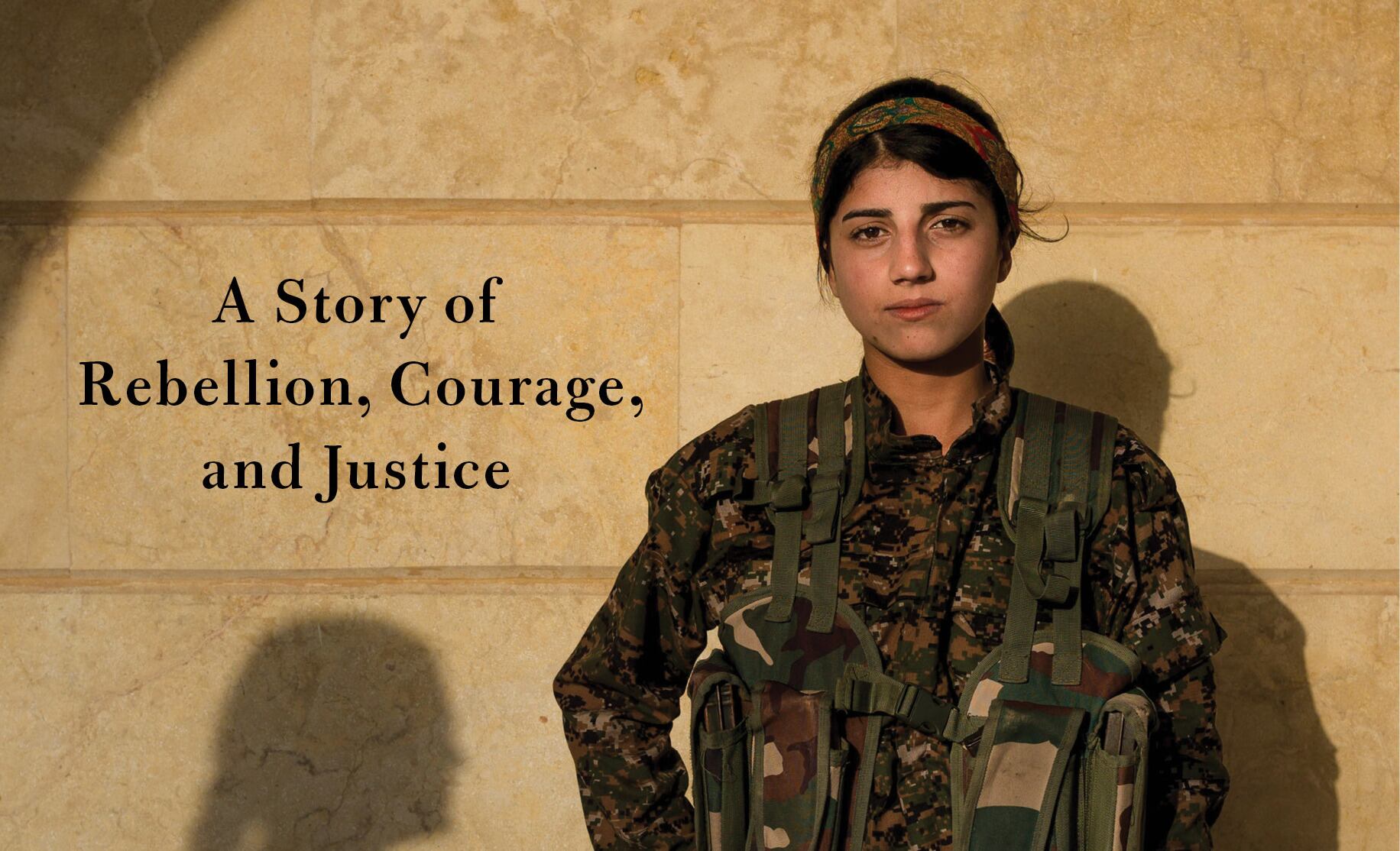

In 2014, northeastern Syria might have been the last place you would expect to find a revolution centered on women’s rights. But that year, an all-female militia faced off against ISIS in a little town few had ever heard of: Kobani. By then, the Islamic State had swept across vast swaths of the country, taking town after town and spreading terror as the civil war burned all around it. From that unlikely showdown in Kobani emerged a fighting force that would wage war against ISIS across northern Syria alongside the United States. In the process, these women would spread their own political vision, determined to make women’s equality a reality by fighting — house by house, street by street, city by city — the men who bought and sold women.

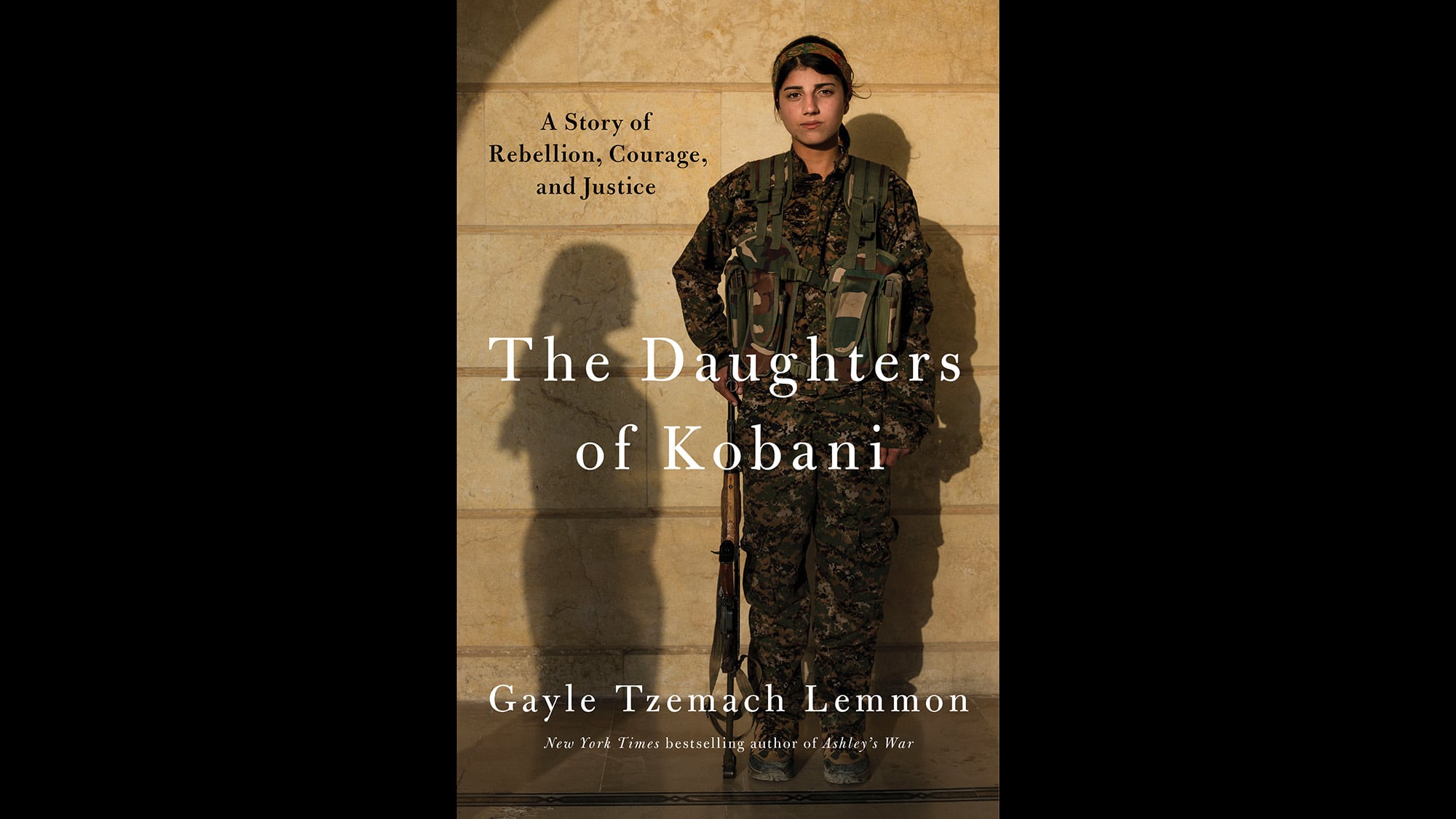

Based on years of on-the-ground reporting, “The Daughters of Kobani” is the unforgettable story of the women of the Kurdish militia that improbably became part of the world’s best hope for stopping ISIS in Syria. Drawing from hundreds of hours of interviews, bestselling author Gayle Tzemach Lemmon introduces us to the women fighting on the front lines, determined to not only extinguish the terror of ISIS but also prove that women could lead in war and must enjoy equal rights come the peace. In helping to cement the territorial defeat of ISIS, whose savagery toward women astounded the world, these women played a central role in neutralizing the threat the group posed worldwide. In the process they earned the respect — and significant military support — of U.S. Special Operations Forces.

Rigorously reported and powerfully told, “The Daughters of Kobani” shines a light on a group of women intent on not only defeating the Islamic State on the battlefield but also changing women’s lives in their corner of the Middle East and beyond.

RELATED

Chapter seven

Nowruz stood on a hill overlooking the banks of the Euphrates River under a black night sky and watched the stream of rubber Zodiac boats set out on their crossing toward the town of Manbij. She barely noticed the booming sounds of mortar fire coming from her side, like a fireworks show that did not end, which was aimed at keeping ISIS at bay and preventing them from shooting at the SDF forces now gliding across the water. She thought only of her hope that the winds would stay manageable so that her troops would arrive safely at their destination, just as they had planned and prepared, over and over again, for two months. The waves churned high, and the skies looked as if they might open up and pelt rain down on them in an instant.

It cannot rain, she thought. We need a quiet, clear night, just as the forecast promised.

The commander held her radio in her right hand and checked her black digital watch: it read 11:03 p.m. on May 30, 2016. Nowruz looked down at the scene just beginning to unfold below and saw staggered rows of small boats, women fighters on each one, including the first. They had come to take back ISIS’s last territorial connection to the outside world: its border with Turkey in the town of Manbij.

For two and a half years, the residents of Manbij had lived under the black flag of ISIS. Beheadings and hangings had become regular occurrences from which parents shielded their children by covering their eyes when they stepped out onto the streets. Home to an Arab majority, Manbij, whose population numbered around three hundred thousand, also included a Kurdish minority that accounted for around a quarter of citizens. The city had attracted attention because it served as the transit point for the foreign fighters who fueled the expansion of the Islamic State. When international ISIS followers arrived in Syria from across the globe—from Europe to the Middle East to Africa and beyond—they traveled through the town and, from there, to the front. Now those same fighters had been called back to Manbij to defend it against the impending attack from the U.S.‑backed SDF forces, of which Nowruz and the women’s units formed a crucial part.

Manbij’s strategic significance to ISIS meant that the town was a crucial next target for the SDF. The fact that the men who carried out the November 2015 Paris attacks had come through Manbij strengthened their case with U.S. diplomats, who strongly agreed. For months, the U.S. delayed the offensive while discussing with Turkey whether the SDF in general and the Kurds specifically could cross the Euphrates River and push ISIS out or whether a Turkish‑backed force would do it. At last, the debate ended with the decision that the SDF was the only force capable of the mission, and the U.S. pledged to Turkey that Arabs, not Kurds, would lead the operation.

Now, as Nowruz and her team faced the challenge of actually executing the mission alongside Arab forces, a slew of complications lay before them. The YPG had the command and control experience and the relationships with the Americans. Arab commanders, including those of the newly formed Manbij Military Council, would lead their forces to take terrain alongside the YPG and YPJ. No one involved had managed an operation this complicated, and while the groups would work together in the campaign under the same flag, the units would not have to integrate at the ground level. There was no bridge across the river; crossing by boat was the only way Nowruz’s forces could reach Manbij. Nowruz watched while they began their biggest operation yet: a water crossing in the dead of night, with ISIS waiting to defend its stronghold on the other side.

She had worried for weeks while they planned the offensive. Crossing the water complicated just about everything. The boats couldn’t carry heavy weapons. Her forces would be visible to ISIS fighters, who would have the high ground on the other side and could easily pick them off. They also would be vulnerable to the weather: if a surprise storm arose, they would have to figure out how to rescue their forces from the watery darkness, and their supplies could topple into the river, never to be recovered. So much could go wrong, she thought to herself. Have we planned for all of it? Could we?

And all those worries surfaced before the SDF even reached the other side. Crossing the Euphrates River was just one piece of the mission: after that, they had to fight to retake the town, and the offensive would doubtless be brutal and bloody. ISIS had spent more than two years digging into their positions in the city, and some of the most glittering names on the ISIS roster called it home. She had a YPJ team ready to de-mine the area where they would build the first road toward the city center; by now they knew ISIS would leave improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, all along the terrain from the river to the town.

War had made Nowruz even more of a planner than she had been as a girl who dreamed of becoming a doctor. Starting at the end of March, she and her fellow leaders met regularly with the Americans to discuss exactly how the mission should proceed. Leo James by now had come back to Syria from Iraq and formed part of the U.S. team that would advise on the mission, though Americans could not cross the river at the outset, given their mandate to stay behind the front line. All the senior SDF commanders who were involved gathered early in May to talk through the logistics of the operation.

Nowruz told the assembled field commanders that part of the overall campaign to push ISIS out of Manbij would include the YPJ executing the water crossing first; this would be the greatest tactical challenge they had yet faced as a fighting force. They would pursue the campaign from two points, the Qara Qowzak Bridge and the Tishreen Dam. To succeed, several thousand fighters would have to cross the water at night, knowing that explosives, snipers, and rocket‑propelled grenades might well lie in wait for them on the other side.

The YPJ women would go first, and their fellow SDF forces, including the Arab fighters the U.S. had promised the Turks were at the fore of the campaign, would be right there behind them. Once they survived the nighttime water crossing, their job was to secure the riverbank. Then the SDF would bring across cars and tanks and heavy weapons. This was just the first of multiple phases of the campaign that would see a number of groups united under the SDF coalition enter the city at different locations and different times to keep ISIS on the defensive.

“We have to force Daesh to choose where to put their resources and their forces by attacking them from different sides and exploiting their weaknesses,” Nowruz continued. “The Americans will help us from the air while we bring everybody across.” Once they got over the hill on the riverbank and into the city, she told them, the fight would get harder. They would need to take as much terrain as they could while they still had an element of surprise.

Five days before the crossing, she and her fellow Syrian commanders from the SDF had convened for a final planning meeting. They had spent hours with the Americans poring over a three‑dimensional model of the terrain, what they called a “sand table,” so that everyone could talk through how the crossing would unfold and craft contingencies for what they would do if plans fell apart. A half dozen men and a few women had lined up around the rectangular replica, which consisted of rust‑colored terrain surrounded by blue water and spanned much of the length of the room. They discussed the minute‑by‑minute details of the attack’s sequencing, hashing out who would cross from which point on the bank at what point in the night.

Nowruz felt that the YPJ had shown sufficient discipline and effectiveness to launch the crossing. Arab fighters would be part of leading this attack, and she wanted her forces to go alongside them, clearing the path by leading in small units to repel ISIS. The all‑women’s forces knew how to set passable routes for people to safely cross newly held terrain, how to establish checkpoints, and how to control the land they had seized. Now they would take the lead in doing so.

Of course, Nowruz knew that the YPJ leading the boats across the Euphrates meant that if anything went wrong along the way, the all‑female units would own the failure. It was only one part of the campaign, but a crucial piece that would set the tone for what followed.

Nowruz had spent the previous day getting ready—going without sleep for more than twenty‑four hours—and had been on the radio since early evening, just after a group dinner of chicken and rice. She had listened to all the teams check in while preparations for the late‑night crossing got under way.

Since the battle for Kobani, she had realized the importance of putting forward the most unflappable front possible; her troops knew her for her cool, even amid the choppiest waters. But here on this hilltop, cupping her radio in her hand as she strained to hear news of the crossing, her hair knotted in a short ponytail just below her ears, looking down at her lined white notebook full of plans, she felt the nerves in her stomach jangling.

The water crossing, she knew, was a tremendous risk. Some of her forces were scared of the river; few of them knew how to swim. The Americans had offered everyone flotation devices, but almost none of her team accepted them; the vests and other gear were too heavy. A sense of fatalism among the Syrians overrode the Americans’ push for them to put on the survival gear.

“If I am going to make it, I’ll make it,” one of the young women had told Leo James when he and his counterparts from the U.S. Navy tried to give her their heavy flotation equipment. “If not, it’s not your life vest that is going to make the difference. I won’t wear that.” Nowruz and her fighters had trained and rehearsed again and again for this night. But all those plans would soon encounter the next force that would get a say in how smoothly the offensive went: the Islamic State. And there was still that list of things she couldn’t control: the weather, the waves, her teammates’ fears, their inability to swim, the certain counterattack by ISIS—which combined to give her the most anxious night she had experienced since Kobani.

Just then she heard a voice on the radio. It was one of her commanders, a young woman named Raheema.

“Haval Nowruz, we are on the boat,” she said.

“Okay, good, Haval, let me know how things proceed,” Nowruz responded.

Less than ten minutes later, Raheema came back on the radio. “We have started driving; we are on the water and moving forward,” she said.

The offensive was officially under way.

On the hill above the riverbank, Nowruz paced back and forth while the scene unfolded below. The sight of the boats crossing against the grey‑black of the sky was beautiful. She pushed from her mind her worst‑case scenario: one of her fighters falling into the water as they battled thirty‑to‑forty‑knot winds with no one aware until it was too late.

Raheema confirmed that they had reached the middle of the river a few minutes later. This time, Nowruz strained to make out the words over the sound of the Zodiac’s motor and the waves crashing. She tried to imagine what the scene looked like to Raheema and the other women in the lead boats. Snipers, mines, grenades—she expected that ISIS had had time to put all of these in place, but she couldn’t know for sure. They were sailing quite literally into the unknown as they crossed on the reinforced inflatable boats.

The radio sputtered, and Raheema’s voice broke into her thoughts.

“We made it. We are across,” Raheema said. She whispered into the radio, trying to speak loudly enough for Nowruz to understand her but quietly enough to keep ISIS from hearing.

Nowruz caught Raheema’s words and allowed herself a moment of relief. But in the next moment, her thoughts shifted to twin concerns: She now had to follow Raheema and her team as they made their way to high ground in Manbij and to coordinate their positions while avoiding ISIS attacks. And she still had a whole night’s worth of boat crossings to track.

“The Daughters of Kobani” is available for purchase here.

Gayle Tzemach Lemmon is the author of the New York Times bestsellers “Ashley’s War” and “The Dressmaker of Khair Khana” and an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. She regularly appears on CNN, PBS, MSNBC, and NPR, and she has spoken on national security topics at the Aspen Security Forum, Clinton Global Initiative, and TED. A graduate of Harvard Business School, she serves on the board of Mercy Corps and is a member of the Bretton Woods Committee.

Editor’s note: This is an op-ed and as such, the opinions expressed are those of the author. If you would like to respond, or have an editorial of your own you would like to submit, please contact Military Times managing editor Howard Altman, haltman@militarytimes.com.