This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Between the villages of Vierville-sur-Mer and Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes in Normandy, France, is a 5-mile stretch of beach that was once called Côte d’Or, or “golden coast.”

Since June 6, 1944, however, this beach has borne a different name: Omaha.

Eighty years ago, on a day now known as D-Day, thousands of Allied soldiers crossed the choppy waters of the English Channel by air and sea to land on beaches and coastal areas of Normandy, France, to destroy the Nazi invaders and defeat Hitler’s regime.

Within the military collections of the National Museum of American History, where I am a curator of modern military history, several artifacts collected over the decades help tell the story of Omaha Beach and the invasion landings on D-Day.

A letter from a general

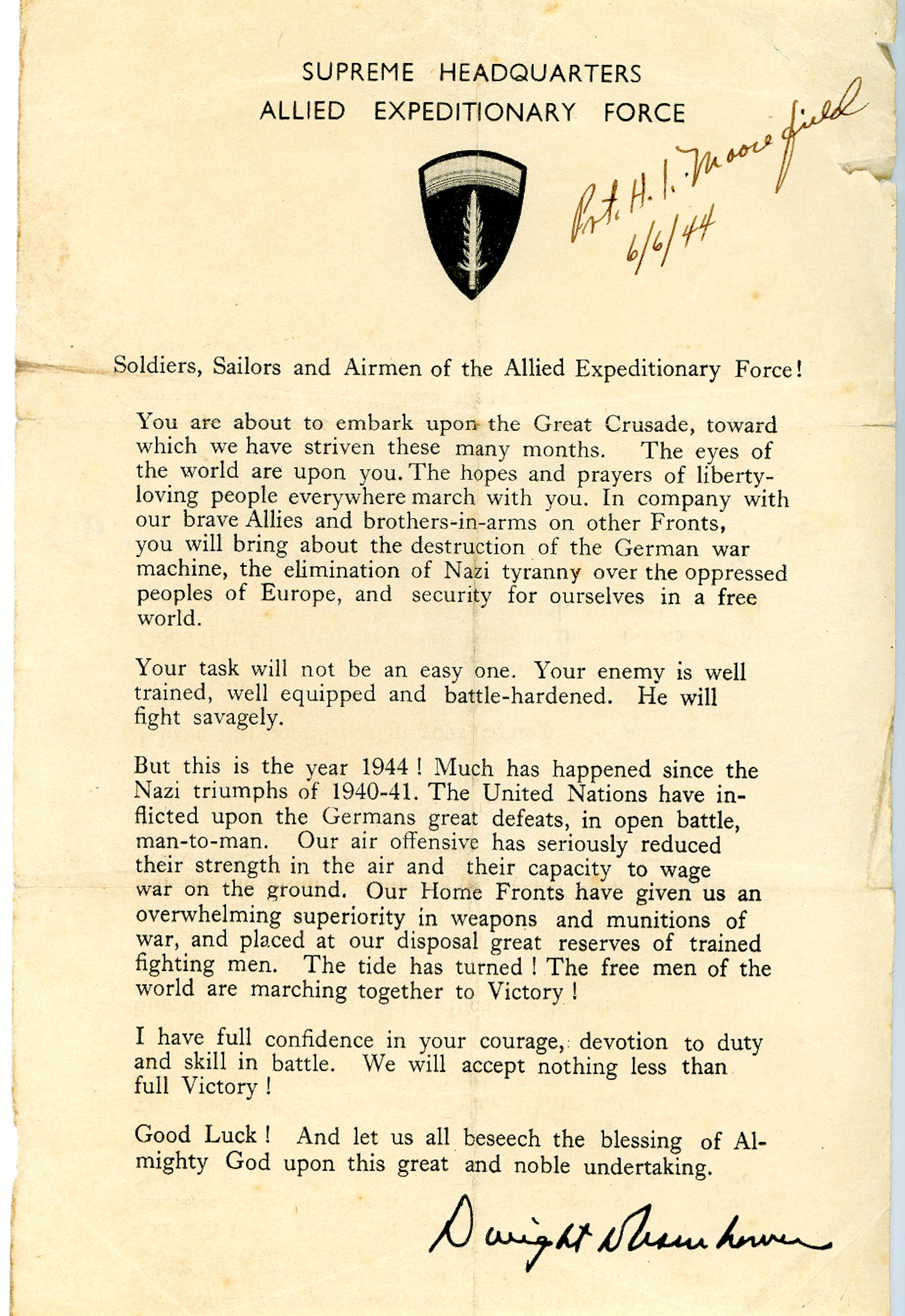

In the morning hours of D-Day, Pvt. Howard I. Moorefield of North Carolina was handed a piece of paper. As he later wrote in his museum donation, “most fellows read it and discarded,” but he chose to sign, fold and save his copy.

With the signature of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower at the bottom, the Order of the Day declared to all soldiers, sailors and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force: “You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you.”

Special equipment goes wrong

For soldiers of Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, the Order of the Day mattered less than what awaited them at Sector Dog Green on Omaha Beach. Awakened aboard their troopship around 2 a.m., the soldiers pulled on their equipment. The regiment had been overseas since October 1942, preparing for this critical day with carefully rehearsed drills and training operations.

Yet just days before the invasion, the men received new U.S. Army assault jackets, made to help the first wave of soldiers as they carried ashore ammunition, TNT, a first-aid kit and other equipment. Once loaded, each jacket added upward of 60 pounds onto each soldier’s load.

As Company A’s six landing craft began to head to Sector Dog Green, one of the craft began to take on water. As men entered the deep water, the assault jackets became anchors, the cotton straps swelling in seawater and making removal of the garment almost impossible. Dozens of men drowned while others staggered ashore, exhausted.

The troops in Company A had expected to find shelter on the beach, which they had been told would be pockmarked with holes from aerial bombing and naval rockets. But when the soldiers in the surviving five landing craft arrived on the beach at 6:36 a.m., they found smooth sand and nowhere to hide from the enemy.

In less than 10 minutes, German machine-gun fire, mortars and artillery all but destroyed Company A.

Other companies of the 116th would land on Omaha Beach at sectors Dog White, Dog Red and Easy Green. Wet, cold, frightened and pinned down by enemy fire, many soldiers shed the awkward assault jackets and did what they could to stay alive and get off the beach.

In the days after D-Day, assault jackets littered the beaches. One veteran of “Bloody Omaha” chose to send a vest back home to Virginia, the fate of its former wearer unknown.

Multiple waves of troops

Farther down Omaha Beach at Sector Easy Red, photographer Robert Capa arrived at the shore around 8:15 a.m. with the command group of Company E, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division.

As part of the 13th wave of the landings, he spent 30 minutes on the beach capturing images of the invasion before returning to the attack transport vessel USS Samuel Chase.

On June 19, five of Capa’s images graced the pages of Life magazine, bringing the invasion home to Americans.

A symbol of the fight’s significance

As Capa arrived back aboard the Chase, so did countless wounded men from the initial assault waves. Navy and Coast Guard personnel went right to work, including Walter Melville Weberbauer, a pharmacist’s mate first class from New Jersey.

As he aided the treatment of the wounded, the identification tags around his neck included a small copper coin — a British Palestine 2 mils.

Perhaps during prayer or just for luck, he rubbed the coin until the word “Palestine” all but wore away. As a Jewish man, Weberbauer’s fight with the Nazis understandably carried great significance in the waters off Omaha Beach.

The nation’s highest military decoration

As wounded soldiers kept arriving back aboard the USS Samuel Chase throughout the afternoon, Army leaders decided to land the remaining members of the 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, on Omaha Beach.

That evening, the men of Company H of the 26th disembarked from the ship and came ashore, including a machine-gunner, Pfc. Francis X. McGraw of New Jersey. Having already fought in North Africa and Sicily, Normandy would be McGraw’s third fight with the Nazis. Months later, on Nov. 19, 1944, near the German town of Schevenhütte, McGraw’s war would end.

For his one-man stand against a ferocious German assault, he would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor.

A record in the landscape

In the days and weeks after June 6, Omaha Beach was transformed into a highway for Allied men and material entering Europe. This traffic changed even the sand itself.

Today, 4% of the sand at Omaha Beach is composed of tiny grains of iron, mostly microshrapnel produced during intense fighting on the beach and the subsequent buildup of forces.

These different items — a document, garment, photographs, identification tags, a decoration and sand — all remain indelibly marked by a time and a place.

Through the linkage of time, space and memory, these items weave together lives whose paths crossed, in the words of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the “fight to end conquest … to liberate … to let justice arise, and tolerance and good will among all … people.”