The Army has no plans to mirror an order by the Marine Corps commandant instructing his subordinates to remove Confederate-related paraphernalia from bases across the world, according to the service.

The Marine Corps’ decision comes the same month as a congressional hearing discussed the rise of white nationalism and extremism in the military, an issue closely tied with the presence of Confederate monuments, flags and naming conventions.

“We have no plans to rename any street or installation, including those named for Confederate generals,” an Army spokesperson said.

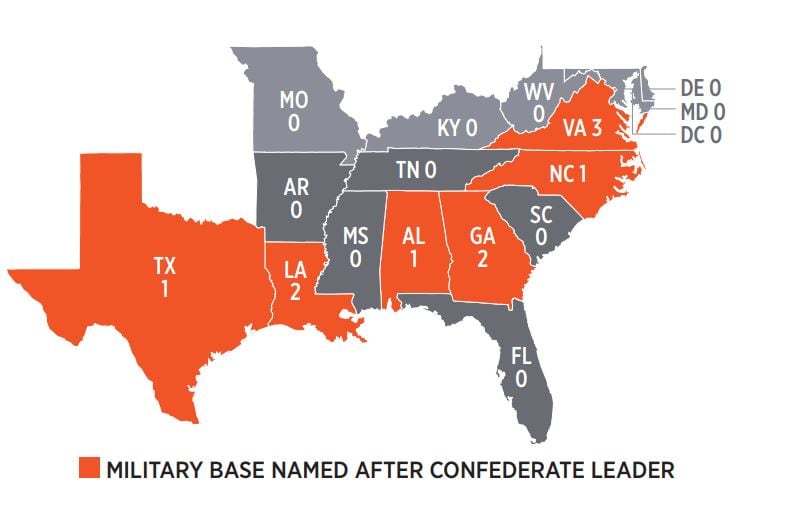

The Army operates 10 installations named after Confederate military commanders, including Fort Lee in Virginia, Fort Hood in Texas, and Fort Bragg in North Carolina. There are no such installations for the other military departments, according to the Congressional Research Service, though some Navy ships have been named after Confederate officers or battles.

“It is important to note that the naming of installations and streets was done in a spirit of reconciliation, not to demonstrate support for any particular cause or ideology," a statement from the Army’s public affairs office said in response to several queries. “The Army has a tradition of naming installations and streets after historical figures of military significance, including former Union and Confederate general officers.”

Discussions surrounding renaming bases can be difficult, but momentum is growing in support of that effort, said Mike Jason, a retired Army colonel. Jason recalled a brigade commander he had at the 3rd Infantry Division in the late 2000s who ordered all the Confederate prints removed from their conference room.

“There were these cheap, kind of replica, little prints of Civil War officers on the walls,” Jason said. “And the stuff just came down. There was no blow-back or dust-up with the [inspector general]. It was just sort of like ‘yeah, that makes complete sense.’”

The names of barracks, bases and streets matter, because it’s part of the story the Army is telling young troops, Jason said. Some have suggested that Army bases with the names of Confederate leaders should be renamed after Medal of Honor recipients.

“It’s not about negating the past," Jason added. “We’re an evolved and inclusive military now and we have a lot of new heroes who deserve to have their names emboldened in history.”

The decision by the Marine Corps is likely far easier than what the Army faces. The Marines have fewer bases and did not have the same sort of Civil War presence that can be used to justify honoring Confederate leaders.

Confederate Army commander Gen. Robert E. Lee, for instance, has a barracks named after him at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, an institution he graduated from in 1829.

Lee Barracks only opened in the early 1960s, though, a time when the civil rights movement was gaining momentum.

“By honoring Lee, the barracks remain tied to a legacy of racism, slavery, and the willingness to assume arms against the United States to defend these heinous practices,” West Point graduate Bejamin Haas wrote in an August 2017 op-ed, arguing for the barracks to be renamed.

Although Lee is also known for his strategic skills on the battlefield, “it remains indisputable that he is most prominently recognized for leading the Confederate Army,” Haas wrote. “As such, Lee Barracks is most naturally construed as an endorsement of Lee in this role.”

Near Lee Barracks are even newer living quarters named after Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a 1936 West Point graduate who went on to lead the World War II-era Tuskegee Airmen and became the first African-American general officer in the Air Force.

During his time at West Point, Davis was ostracized by his white classmates, who hoped the silent treatment would encourage him to leave the academy. Instead, it hardened Davis’ resolve.

“As a black Army captain and West Point graduate who lived in General Robert E. Lee barracks as a cadet, this was a particularly meaningful morning for me,” Timothy Berry, an Army officer and West Point graduate, wrote in an op-ed after he attended the opening of Davis Barracks.

“We should not view the renaming or removing of these Confederate monuments as a sign of a lost history, but as an opportunity to highlight those unsung heroes who personified the highest virtues that initiate action for the greater good," Berry wrote.

The controversy over Confederate symbolism has also coincided with an apparent rise in white nationalism in the U.S. military’s ranks.

New data from a Military Times poll conducted last fall showed more than one-third of active-duty troops polled and more than half of minority service members polled have seen examples of white nationalism or ideological-driven racism among their fellow troops.

The 2019 survey found that 36 percent of troops who responded have seen evidence of white supremacist and racist ideologies in the military, a significant rise from the year before, when only 22 percent — about 1 in 5 — reported the same in the 2018 poll.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.