A 40-page policy proposal to address racism at the U.S. Military Academy in New York, written by nine recent graduates, includes testimony from cadets who said they endured racial slurs and racially-based harassment that wasn’t properly investigated when reported.

The alumni emailed their proposal June 25 to the academy’s leadership. On Friday, West Point’s Inspector General’s Office started a “comprehensive review of all matters involving race,” academy spokesman Lt. Col. Christopher Ophardt told Army Times.

The alumni’s policy proposal included some searing indictments of the academy’s culture.

“I was called a ‘n-----’ during my plebe year,” said one cadet in testimony drawn from a spring 2020 survey. “When I reported it to my Tactical Officer, they instead accused me of lying and initiated an honor investigation against me.”

Another cadet said he was told the “only reason” he was accepted was because he was “Black and on the football team.” A separate cadet recalled a student making a noose and putting it “on his Black roommate’s desk as a joke.”

Yet another cadet described seeing Black students face harsher punishments than white peers, including an instance in which a Black cadet “committed an infraction and received a company board with walking hours, whereas a Caucasian Cadet committed the same infraction and received only a verbal warning.”

The testimonies were peppered throughout the larger policy proposal, which was signed by nine alumni with impressive resumes, including valedictorians, Fullbright Scholars and a class president. The document called on West Point to remove monuments honoring Confederate leaders, promote more academic work by marginalized people and institute anti-racism training.

Ophardt, the academy spokesman, said West Point began looking at issues of race earlier in June as part of a larger Department of the Army initiative to reduce racial bias within the service.

While he did not link the inspector general’s review to the policy proposal, Ophardt said the inquiry “will be all-encompassing,” meaning it will also examine the issues raised by the nine alumni.

RELATED

“We take seriously all forms of racial inequality that marginalize or devalue members of our team. West Point does not accept, condone or promote racism,” Ophardt said in a statement. “The West Point Inspector General has begun a comprehensive review of all matters involving race at the Academy. We will carefully consider the results of this review and deliberately address any findings.”

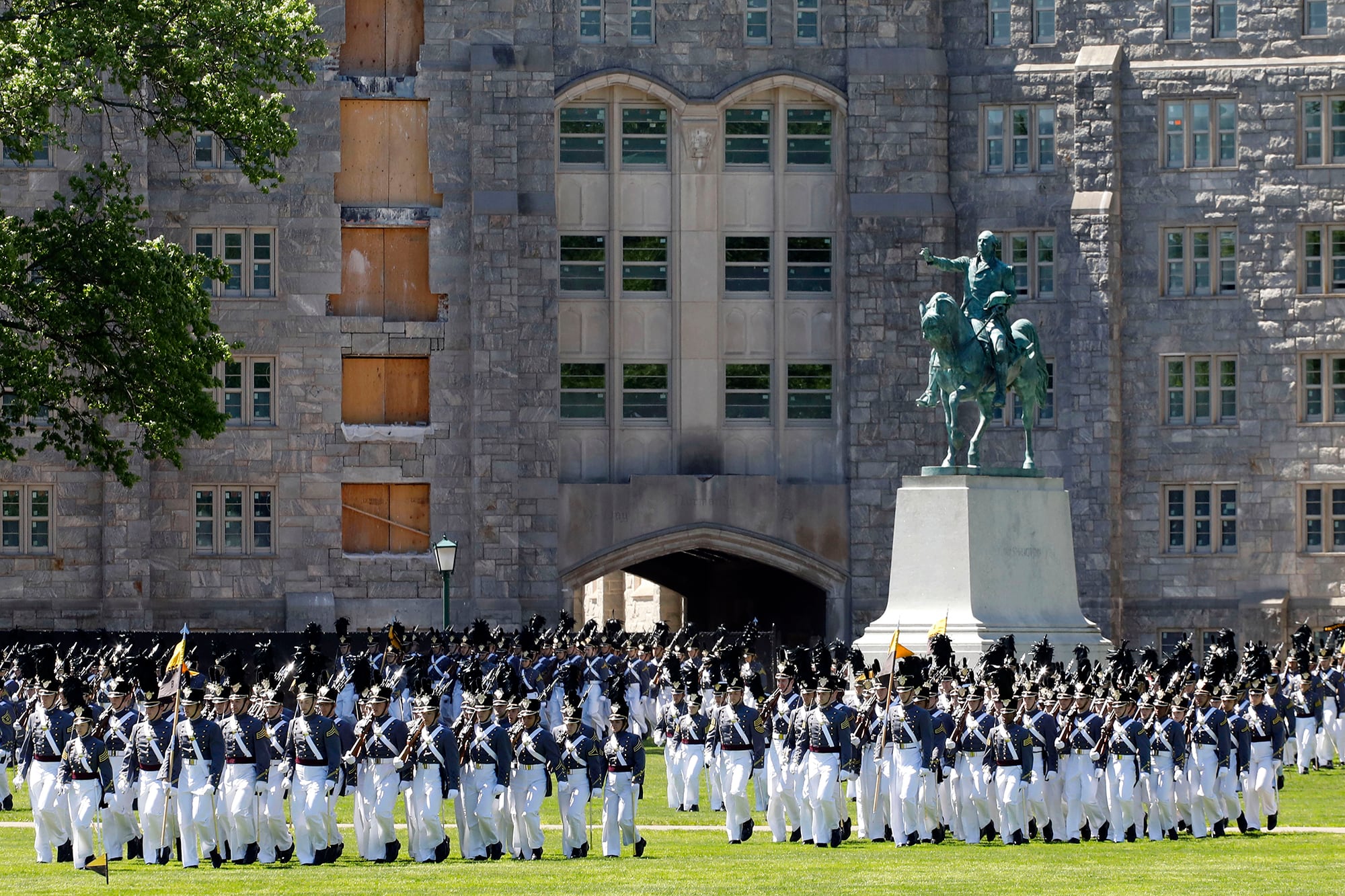

West Point’s review will look at the cadet honor code and how it’s being enforced, the academy’s educational programs and campus monuments. The policy proposal written by the alumni called for West Point to remove all names, monuments, and art “honoring or venerating” Confederate figures.

“A Cadet wakes up in Lee Barracks, which is named for Robert E. Lee, the West Point graduate who betrayed his country for the worst possible reason: to protect ‘states’ rights’ to own slaves,” the document reads. “This barracks in his name was not dedicated following the Civil War as a gesture of reconciliation, but in 1970, amidst the Civil Rights Movement.”

“The Cadet walks out of Lee Barracks and past Reconciliation Plaza, a monument built as recently as 2001, which bears a list of the names of those Confederate Officers who graduated from West Point,” the document stated. “What does an experience soaked in such romanticized remembrance of white supremacy teach a Cadet about the history of our nation?”

Lee, who served as the commander of the Confederate Army during the Civil War, was appointed to be West Point’s superintendent in 1852. A 6-foot portrait of Lee still hangs in the library on campus with a Black slave standing in the bottom right corner leading Lee’s horse.

However, the current superintendent, Lt. Gen. Darryl Williams, “replaced [another] portrait of Lee hanging prominently in his living room of Quarters 100 with one depicting U.S. Army General Ulysses S. Grant,” the alumni wrote.

Williams became the first Black superintendent of West Point in the summer of 2018. The policy proposal alleged that attempts to remove other Confederate memorials were stymied by former Defense Secretary James Mattis, who urged academy leaders “not to get ahead of the Army.”

“Is it any wonder that the Lee painting was removed without any official statement — that it had to be done secretly?” the alumni wrote in their proposal. “Will this painting resurface when the Black Superintendent leaves?”

While the nine alumni are not speaking to the media, a mentor for some of them named Mary Tobin spoke with NPR’s Morning Edition Monday.

“For cadets, especially cadets of color, addressing systemic racism is a part of a long legacy we have at West Point,” Tobin, who is also a West Point graduate, told the national radio broadcaster.

Tobin said she believes the U.S. military is still “predominantly” a meritocratic organization. But she said the armed services should be more intentional about addressing biases and promoting racial tolerance.

“All that meritocracy is subject to the subjectivity of a person,” Tobin said. “The military is a literal representation of society.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.