The Army has announced servicewide and command-specific changes in the wake of a scathing independent report last year that called for a major overhaul of both its Criminal Investigation Command and its Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention Program.

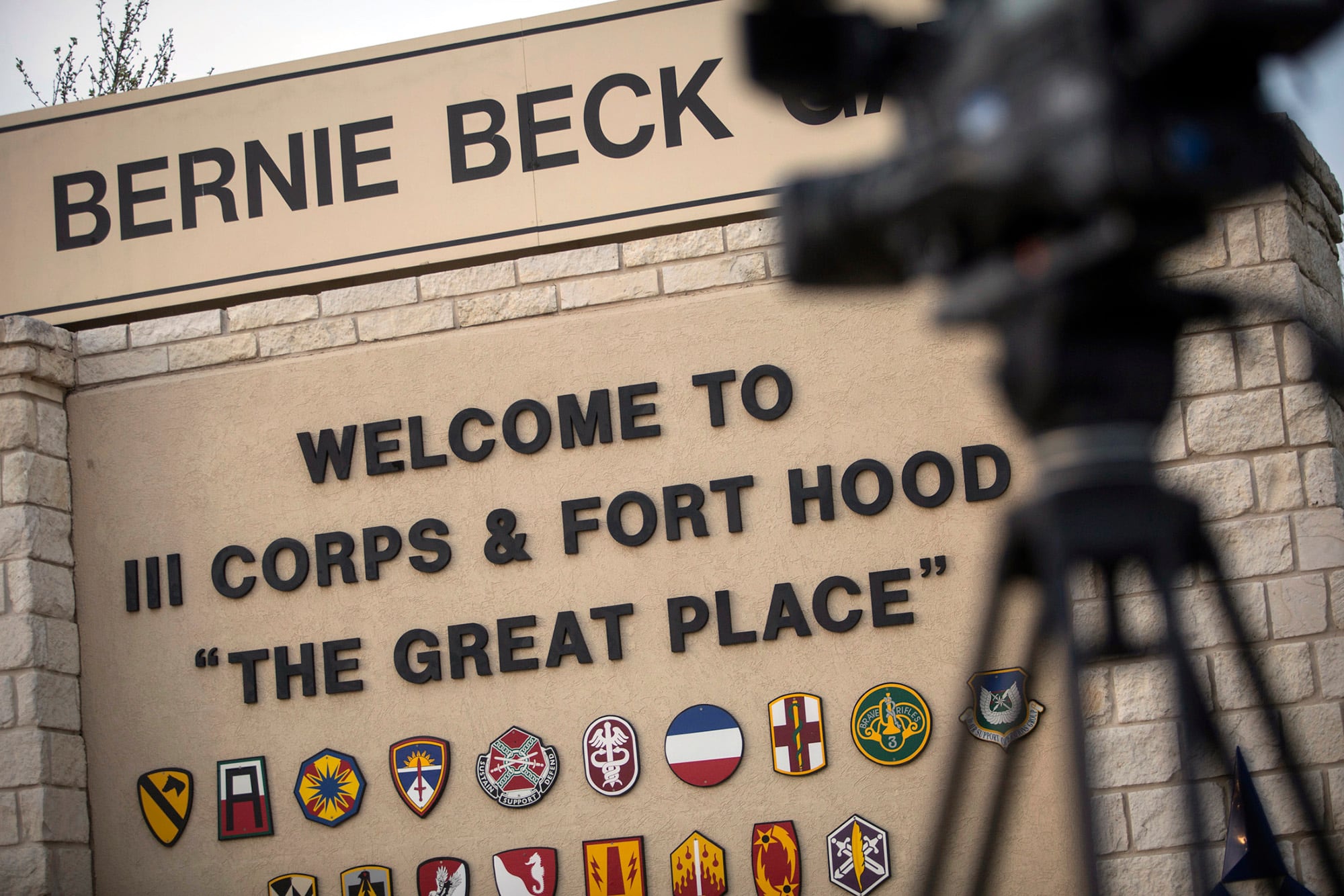

The changes come after a public furor arose last year over the alarming number of murders, suicides, sexual assaults and incidents of harassment at Fort Hood, Texas. The most prominent of those was Spc. Vanessa Guillen, a 3rd Cavalry Regiment soldier killed inside the unit’s armory by a soldier. Before her death, Guillen had told her family that she was being sexually harassed by a soldier, although it was later determined that he was not involved in her death.

One major policy change already implemented at the Texas post — which is likely to go Army-wide once approved — is that soldiers who report sexual harassment or assault will see their case handled by an investigating officer outside their chain of command.

RELATED

Though the installation’s problems came to prominence last year, the Fort Hood Independent Review Committee report noted that as early as 2014 major issues were being identified and that Fort Hood leadership, “knew or should have known of the high risk of sexual assault and harassment at the post.”

Fourteen Fort Hood leaders were relieved or suspended following the report’s release.

But the Army acknowledged that such problems were not unique to that installation and established a task force late last year to implement changes and restructure major entities within the service.

Three co-chairs of the People First Task Force briefed media in a telephone interview session Friday, providing an update on work done so far.

The task force is co-chaired by Lt. Gen. Gary M. Brito, the deputy chief of staff for Army personnel; Sgt. Maj. Julie A.M. Guerra, the Army intelligence (G-2) sergeant major at the Pentagon; and Diana M. Randon, deputy assistant chief of staff for intelligence.

While detailed changes of how problems at Fort Hood and, in some cases, the Army as a whole are being addressed, the task force is in the process of redesigning the Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention, or SHARP, program.

The task force expects the redesigned SHARP program will look out for the best interest of soldiers and civilians by focusing on prevention, survivor support and holding leaders at all echelons accountable,” according to the Army statement.

“We took a wide-eyed open look at the entire program,” Brito said. “We took a look at the structure and support given to soldiers, civilians and facilities as well and how to improve a program that provides proper prevention and support.”

Though details of the restructuring have not yet been approved, Guerra said one clear problem inside formations is that victim advocates are being assigned cases as an additional duty, perhaps overburdening the NCOs in those positions.

That, along with the way that we hire people to go into these jobs at the brigade and higher level, and then the way that the NCOs are selected, trained and placed into these positions of trust, as … an additional duty and not really as a career track, becomes problematic, too.

“So, from a restructuring standpoint, as General Brito mentioned, we are looking at all of that and how, one, we can do it better and then, two, how we can continue to improve upon things that may be working inside of our formation,” Guerra said.

Including the move to assign an investigating officer outside the chain of command for sexual harassment and assault reports.

“It’s not someone embedded inside of the formation, where they’re investigating their own,” she said.

Randon said that initiative is expected to happen across the Army.

When asked about the timeline, Randon said the policy change is being developed now and has to go through the standard staffing process, but she expects that within the next two weeks a draft policy change will be ready for senior Army leadership.

Nearly half of the 70 recommendations out of the Fort Hood report were related to the SHARP program.

So far, 20 of 70 recommended changes have been or are being implemented, Randon said. But many of the changes happening at the fort could see adoption across the Army.

“What we’re doing is taking those and looking at implementing those across the Army,” Randon said. “What do we do for all three components (active, Guard and Reserve) and civilians. What does it take in regard to policy change?”

“This is building a culture that forever will be different in our Army,” she said.

The changes include the following, according to an Army statement:

Army-wide

- Updated CID policies to require full investigations of off-post soldier drug overdoses, including determination of the source of the drugs and the extent and nature of the Soldier’s involvement with illegal drugs. The updated policy also requires a full investigation of all suspected soldier suicides occurring on or off the installation. (Recommendations No. 41 and 42)

- In December 2020, the Army issued guidance regarding missing soldiers to clarify expectations and responsibilities of unit commanders and Army law-enforcement authorities when accounting for soldiers who are absent from their place of duty. (Recommendations No. 43, 46 and 47)

FORSCOM/III Corps/Fort Hood

- The Army Forces Command commanding general implemented a policy requiring commanders to select investigating officers from outside a subject’s brigade-sized element for formal sexual harassment complaints under Army Regulation 600-20, Chapter 7. (Recommendation No. 13)

- The Department of Emergency Services now provides a brief at each III Corps and Fort Hood company commander and first sergeant course regarding the purpose of military protective orders and how they benefit soldiers, commanders and units. (Recommendation No. 28)

- III Corps now disseminates a monthly “Teal Hash” message to the force that includes the results of court-martial convictions for sexual offenses. (Recommendations No. 29 and 30)

- III Corps commanders are required to update victims on Sexual Assault Review Board (SARB) results within 72 hours. (Recommendation No.31)

- Fort Hood’s CID detachment now has access to state-of-the-art software and digital-forensic-examination tools. (Recommendation No. 36)

- Fort Hood has reinvigorated its Good Order and Discipline Boards and updated its list of off-limits establishments to protect the safety and health of military personnel and their families. (Recommendations No. 52 and 53)

- In October, III Corps and Fort Hood initiated Operation People First, a year-long effort designed to create trustworthy and engaged leaders and build cohesive teams; the initiative includes a leader certification program. (Recommendations No. 44 and 57)

- The Fort Hood installation commander now leads and directs the monthly SARB process. (Recommendation No. 64)

- The FORSCOM commanding general has authorized senior mission commanders to temporarily leverage crisis-response resources, including public affairs, medical, legal, logistics and law-enforcement personnel as needed; Fort Hood has also expanded its outreach to key community groups. (Recommendations No. 66, 67, 68, 69, and 70).

Meanwhile, the Army is also looking at restructuring Army Criminal Investigation Command. The People First Task Force is not involved in those efforts, and deferred questions to other Army entities.

Army Times reported in early March that proposals to restructure CID include recasting it as an independent, civilian-run organization, according to briefing documents. That would come with a price tag estimate of nearly $480 million over a decade.

Those same documents note that CID agents prefer that kind of leadship overhaul. The agency is run by military police officers now.

Another option would keep CID’s basic structure, run by military officers, but add more personnel to the command, sources who spoke on the condition of anonymity told Army Times. That proposal is expected to cost considerably less, roughly $60 million over a two to four year period.

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.