Fourteen leaders at Fort Hood, Texas, from the deputy commander down to the squad level, were relieved or suspended after the Army secretary and chief of staff were handed the results of an independent committee’s review of the command climate there.

The committee determined there was an environment at Fort Hood that allowed sexual assault and harassment to proliferate, and that Army CID agents at the post were under-experienced and over-assigned.

The review also raised concerns about how Sexual Harassment/Assault Response and Prevention programs are conducted across the force, as well as how the Army investigates soldiers’ deaths and disappearances beyond Fort Hood.

“Our charter was to look at Fort Hood and that was what we did. But we are not oblivious to the fact that this is one Army and Fort Hood is potentially emblematic of other things going on in the Army,” said Jack White, an attorney with a background in government investigations who was on the committee.

“SHARP is an Army wide program, so some of our observations, while we saw them at Fort Hood, may very well be similar at other installations,” White added.

The committee’s report was briefed to reporters Tuesday by those who compiled the document. Army leadership said they would use the recommendations in the report to make service-wide changes.

At Fort Hood, the III Corps deputy commander, Maj. Gen. Scott L. Efflandt, as well as the 3rd Cavalry Regiment commander and senior enlisted soldier, Col. Ralph Overland and Command Sgt. Maj. Bradley Knapp, were all relieved, Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy said.

McCarthy also directed the suspension of two 1st Cavalry Division leaders, Maj. Gen. Jeffrey Broadwater and Command Sgt. Maj. Thomas C. Kenny, pending the outcome of a new 15-6 investigation of that unit’s command climate.

Efflandt was left in charge of Fort Hood while the post’s top officer, Lt. Gen. Pat White, had been deployed to Iraq for much of the past year. It is unclear whether White will face any punishment, since the issues raised by the committee also preceded Efflandt’s tenure.

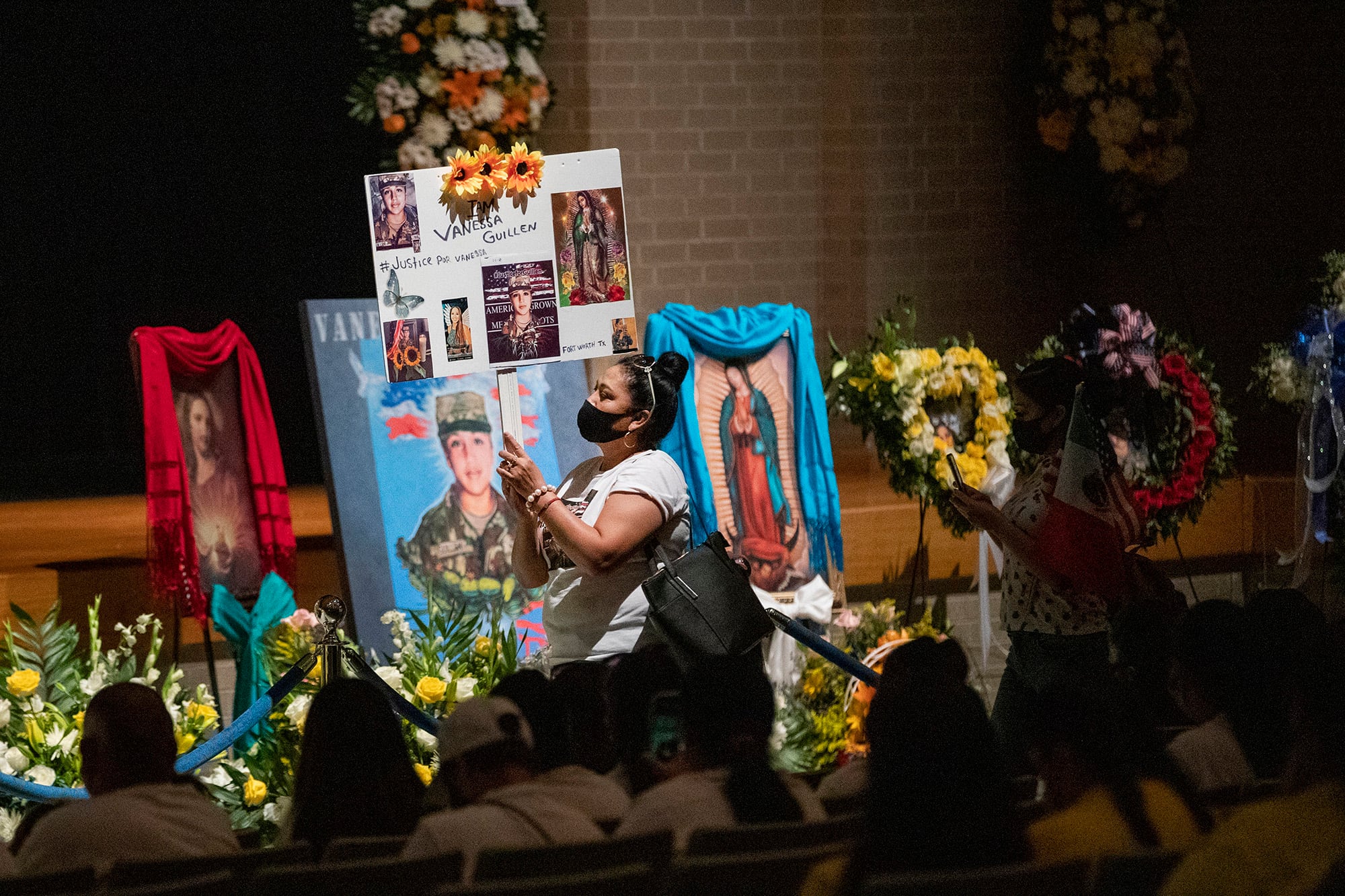

The committee was dispatched to Fort Hood in August following a series of macabre deaths there, including the murder of 3rd Cavalry Regiment trooper Spc. Vanessa Guillen inside an armory, and the subsequent sexual harassment allegations that Guillen’s family brought forth after her death.

But the issues predated Guillen’s case. Fort Hood leadership “knew or should have known of the high risk of sexual assault and harassment” at the post, the committee’s report reads.

“As early as 2014, there were issues that were called out. If you look at it in terms of risk management, it became a known risk very early in the process,” said Chris Swecker, a former FBI inspector who served on the committee.

It was well publicized that the risk for sexual assault at Fort Hood was persistently high, according to the report. This was especially true in the brigades within 1st Cavalry Division and 3rd Cavalry Regiment, where women were first introduced into armored and infantry units more than four years ago, the report added.

“Unfortunately, a ‘business as usual’ approach was taken by Fort Hood leadership causing female soldiers, particularly, in the combat brigades, to slip into survival mode, vulnerable and preyed upon, but fearful to report and be ostracized and re-victimized,” the report reads.

The committee also determined Fort Hood was used as a training ground for CID agents, most of whom were inexperienced and overworked, factors which adversely impacted the investigations of sex crimes and soldier deaths.

Many apprentice CID agents were coming out of training at Fort Leonard Leonard Wood, Mo., and going straight to Fort Hood, according to the report. A review of the agents assigned to Fort Hood in 2019 revealed that 92 percent were fresh out of the 16-week CID Special Agent Course.

“And then within two years they were rotating out very quickly so … there was a lot of attrition of the case agents and the agents working these investigations,” Swecker said.

Fort Hood CID also lacked easy access to the investigative tools that most law enforcement agencies rely on, Swecker said. That includes cell phone tracking and the ability to extract information from mobile devices, “which is very critical investigative techniques in today’s investigations,” he added.

The committee found that the SHARP program at Fort Hood was also ineffective, creating a pervasive lack of confidence, fear of retaliation and significant underreporting of cases, particularly within the enlisted ranks.

Queta Rodriguez, a Marine veteran who served on the committee, said that the number of unreported sex crimes at Fort Hood was “shocking,” and attributed the high numbers to a “lack of confidence in the system.”

“Of the 503 women that we interviewed, we discovered 93 credible accounts of sexual assault. Of those only 59 were reported,” Rodriguez said. “We also found … 217 [credible] accounts of sexual harassment. So that’s a really significant number. Of those, just over half were reported.”

While at Fort Hood, the five civilian committee members and their support staff completed more than 2,500 interviews with soldiers and civilians employed there, including 503 female soldiers from 3rd Cavalry Regiment and 1st Cavalry Division. A hotline also collected more than 31,000 responses to a mandatory, anonymous survey on command climate as it relates to sexual assault or sexual harassment.

The committee put forth nine findings and 70 recommendations relating to Fort Hood’s SHARP program and its CID detachment, protocols concerning missing soldiers, which Army Times has previously reported, and the installation’s crime prevention and public relations efforts.

The recommendations dealt with the structure of the SHARP program, its legal components and disclosure after adjudication of an allegation, which should be published at least semi-annually.

Army CID should also work with local law enforcement to identify high-risk establishments, locations and living areas and “rapidly declare them off limits” to troops, according to the recommendations.

Though the crime rates in the local area “were relatively low in comparison to other cities outside Army installations,” there were high numbers of violent crimes and felonies on Fort Hood, according to Swecker.

“Positive drug tests [at Fort Hood] were the highest in the Army,” said Swecker. “What we found was there were no proactive efforts to suppress crime, to address the drug issues, to address violent crimes.

Suicides were also “extremely high” at Fort Hood, but due to the CID detachment’s inexperience and lack of resources, agents failed to explore the issues behind those suicide numbers, according to Swecker. The number of homicides, however, were not unique.

“There aren’t an anomalous number of death cases at Fort Hood in terms of homicides, but the homicides that did occur got intense media attention,” Swecker said. “And again, what we found in the death cases was CID just needed more experience and continuity inside the detachment there and it may be systemic across CID — that there just isn’t enough longevity at the post on the part of investigators so we made some recommendations regarding making sure there are experienced agents there.”

Though there have been a number of violent deaths among soldiers stationed at Fort Hood, the independent review primarily arose from the questions and concerns voiced by family members, Congress, and various Hispanic advocacy groups during the investigation into the disappearance and murder of Guillen.

Prosecutors say Guillen was killed inside an armory on post by a fellow soldier, Spc. Aaron D. Robinson, 20, who then enlisted the help of his girlfriend to hide Guillen’s remains. A motive for the killing has not been released. Robinson killed himself July 1 when he was confronted by police.

CID said they found no evidence that Robinson sexually harassed Guillen, but an investigation into allegations that she faced such harassment from other soldiers remains underway.

“I don’t want to step on an investigation, but I will say this: There is a misunderstanding on one part of that. CID did not find any evidence that Spc. Robinson sexually harassed Spc. Guillen, and I’ll leave it at that,” Swecker said.

Other investigations sparked by Guillen’s death remain ongoing, including a Government Accountability Office review of the Army’s entire SHARP program and the investigation into Guillen’s sexual harassment allegations.

Rep. Sylvia García, D-Texas, who has worked with the Guillen family throughout their ordeal, said in a statement Tuesday that key issues remain unresolved.

“In light of these findings, I still have many concerns,” García said. “This independent panel did not determine who in the command structure was criminally negligent in Vanessa Guillen’s case, but I hope all who are responsible will be held accountable. They must be held accountable.”

García has been working to pass the I Am Vanessa Guillen Act, legislation that would create an independent and confidential way to report sexual violence for service members.

“This report is just a first step in making sure that what happened to Vanessa Guillen never happens again to another soldier,” García said.

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.