Need substitute teachers? Need medical janitors? Need bus drivers? Need jail guards? Need “mall cops” for the border? Need poll workers? Need to process unemployment claims?

If you’re a governor, you have the authority to deploy your state’s National Guard forces to combat nearly any societal ill with the stroke of a pen. It’s happening more in recent years than ever before.

That’s left some senior Guard leaders worried about becoming America’s “easy button.”

“We have to…avoid becoming the Easy Button,” said Air Force Maj. Gen. Daryl Bohac, Nebraska’s top general, in an October interview published by National Guard Magazine. “There has to be some judicious analysis of whether a particular mission is an appropriate mission set for the Guard.”

Some fear that long-term, constant non-military domestic missions have become the new normal for the National Guard. March marks the third year of this new era of domestic response for the country’s part-time troops.

It began with the COVID-19 pandemic and the Federal Emergency Management Agency cost-sharing agreement, which has troops answering to their governors while on the federal government’s dime.

It’s also led to an uncomfortable tension for the organization, which prides itself as being an adaptable option to accomplish any homeland mission — but it also has never been used so frequently for such a long period of time.

As of Feb. 22, at least 21,400 members of the Guard were activated across the U.S. for domestic missions, according to National Guard Bureau spokesperson Wayne Hall. Although that number doesn’t include all Guard troops on state missions, such as those under Texas’ control assigned to the border, it does include some 17,600 troops assigned to pandemic response.

Some senior leaders are concerned that not all those troops are necessary.

That’s what Maj. Gen. Laura Yeager, commander of the California National Guard’s 40th Infantry Division, seems to think. Yeager, the first woman to command an Army infantry division, said in October that states should have financial “skin in the game” for domestic operations and declared her unit a “victim” of its own success.

“Over the last 18 months, the 100 percent reimbursement of our forces has actually disincentivized the state [from] releasing our forces from the mission,” Yeager said that month at the Association of the U.S. Army conference in Washington. “There were some periods of time where I had medics — I have very limited medical support in my state — [who] were on orders, but they were not on mission for almost two months.”

She declared it “bad for morale,” and said it was also diminishing their equipment readiness.

A hard-to-ditch habit

Even the troops who are “on mission” have seen remarkable mission creep under the federal money spigot, which FEMA has allowed governors to tap to address second-order effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to direct medical support.

“Again, we look at all we’ve been doing in ‘20 and ‘21…is that a sustainable model?” Bohac, Nebraska’s top general, asked in the interview with National Guard Magazine. “Should we be looking more deliberately at the kinds of missions the National Guard is involved in? If it’s in the homeland, does it have a military nexus or not? Does it enhance readiness or does it distract from readiness?”

The Army Guard’s top general, Lt. Gen. Jon Jensen, argued the phenomenon is likely temporary during a Center for a New American Security event on Feb. 22.

“I’d like to believe [the missions are] going to lessen, primarily because at some point, we’re going to leave a COVID-19 environment,” he said. “I think when we see the end of COVID-19 support, we will go back to more of a traditional role — of responding to emergent emergencies that are short duration.”

The data agrees, he said: the number of troops activated for pandemic response is once again decreasing as case numbers and hospitalizations associated with the Omicron variant of the virus decline around the country.

But will governors find it hard to abandon their new habit of calling the Guard for all of their problems?

During the early months of the pandemic, the Guard’s support primarily consisted of work directly adjacent to the medical challenge at hand. That included nursing home decontamination, building field hospitals, gathering and transporting bodies, protective equipment warehousing and more.

Many of those roles dovetailed with specific Guard capabilities: Civil Support Teams, construction engineers and mortuary affairs.

Federal cost-sharing gradually began in late March 2020, mere weeks after governors had started mobilizing their troops for the pandemic. And since then, it hasn’t stopped, save for a brief interlude during which the Trump administration reduced the federal reimbursement rate to 75% for most states.

The arrangement undermined the old concerns that previously reined in excess.

Federal cost-sharing eliminates the influence that finances would have on the governors who wield the Guard, as well as the state legislators who would normally corral a governor who was too loose with the purse strings.

Odd jobs

These dynamics have influenced governors to say “yes” to Guard support for missions addressing second-order pandemic effects that could still be linked to the FEMA mission.

One early example was the Guard’s support to food banks, which were simultaneously seeing increased demand and decreased numbers of volunteers due to the virus.

As the mission wore on, and food bank demand slackened, states began looking to return to normal operations. But the organizations — and governors — were loathe to let them go.

Arizona National Guard officials were unusually frank about those realities when speaking with Green Valley News in February 2021 about their ongoing foodbank support.

“We were called back in March to help the state, and we’re happy to do so, but we can’t do this long term,” said one command sergeant major.

A lieutenant colonel said “our leadership is committed to assisting the food banks, but again, we don’t know what lies ahead.” He called for volunteers to return to the food bank to replace the troops.

Another example of general-purpose Guard labor was Washington State’s summer 2020 mission to process a backlog of unemployment claims that brought the state’s Employment Security Department to its knees.

The Guard did so well in that role that Gov. Jay Inslee again mobilized 50 troops in March 2021 to help the office dig out of a backlog of overpayment claims.

Other later missions received federal reimbursement as well, such as Massachusetts’ highly publicized activation of around 250 Guard troops in October to transport children to schools amid a massive shortage of bus drivers.

Gov. Charlie Baker received credit for the move in the first sentence of national news reports on the mission, which saw troops log 300,000 miles and transport 15,000 students.

Baker told CBS News that the state was being fully-reimbursed by federal authorities.

But it appears that governors’ recent habit of reaching for the Guard button has even led to unprecedented state active duty missions that the federal government may not reimburse.

Two high-profile missions — the New Mexico substitute teachers and Texas’ mission to secure its border with Mexico — stand out because they are being conducted solely using state funds.

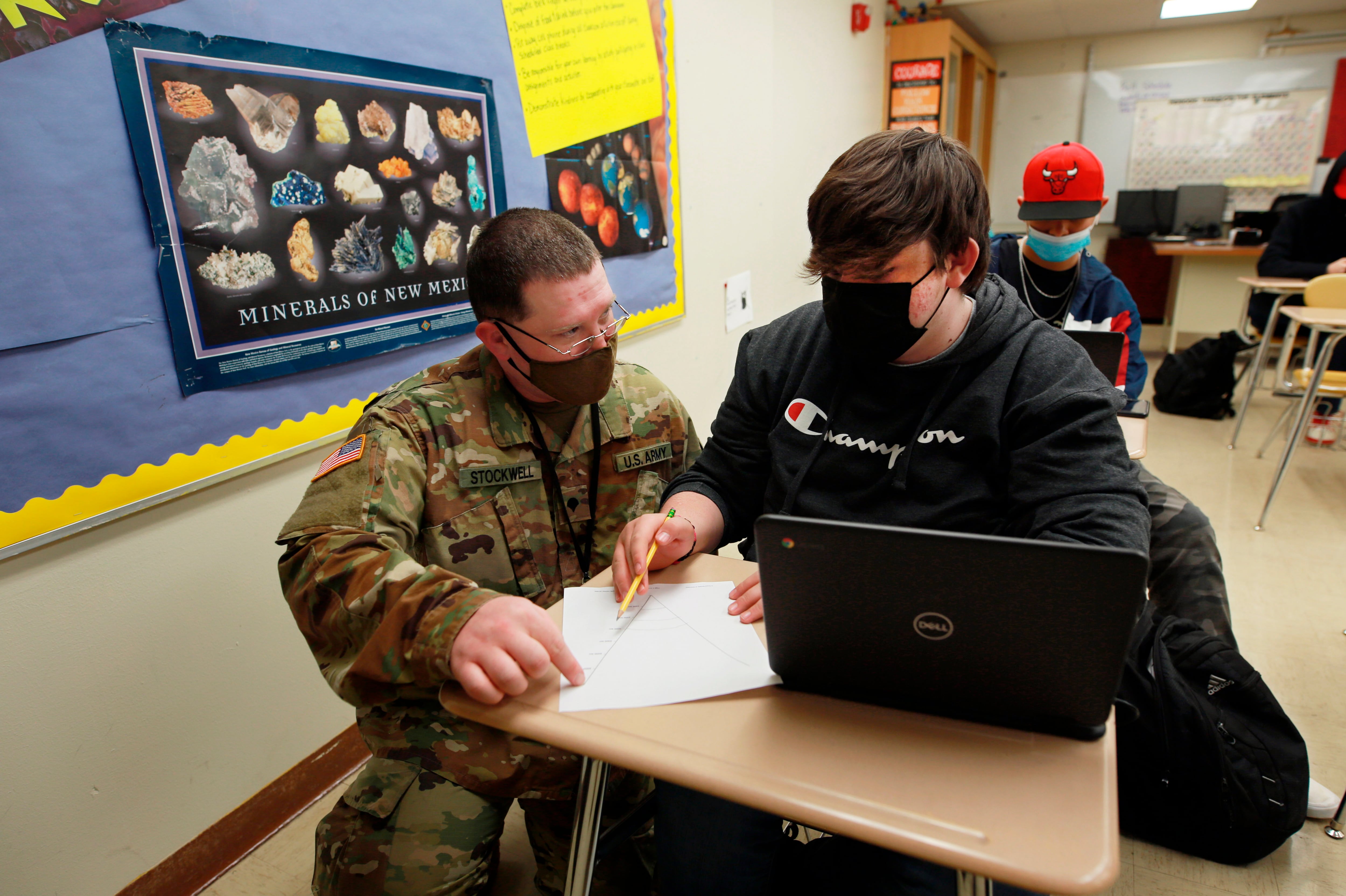

The New Mexico mission began in January as an effort to address problems fielding enough teachers to keep schools open during the Omicron surge. As a result of the virus and the state’s more than 1,000 teacher vacancies, roughly 100 schools have shut down at least one day this school year due to staffing issues.

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham decided to mobilize Guard troops on state active duty and train them to serve as substitute teachers. Nearly 100 Guardsmen have answered the call.

The small, all-volunteer mission is unlikely to harm the state’s ability to complete other missions. But other corners of the Guard have had to work harder to juggle their priorities.

Strains are appearing

Guard officials have stated repeatedly that if push comes to shove, the organization has to prioritize its federal mission requirements over their state missions.

“Our primary purpose in the Army National Guard is to fight our nation’s wars and to secure the homeland as a lethal, cost-effective force,” Jensen, the Army Guard’s top general, explained on Feb. 22 at CNAS. He argued that federal funding and equipment “allows us to organize, train, and equip our force” and make it capable of effectively executing domestic missions. So the priority, at least theoretically, should be to fulfill federal missions.

Jensen was the Minnesota Guard’s top general before arriving at NGB. During his speech at CNAS, he reflected on his struggle to prioritize pre-deployment training in 2020 for the 34th Infantry Division’s 1st Brigade Combat Team, elements of which later played a pivotal role in securing Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul amid the chaotic Afghanistan evacuation.

“Early on…I really protected that unit from any COVID-19 task because I wanted it to purely focus on preparing for [pre-deployment] training,” he said. “When the governor called for the full mobilization [during the George Floyd protests]… we had to bring that unit inbound, but because we had protected them from months and months and months of COVID duty, they had been able to get good enough.”

Jensen said the effort to isolate them from state activation helped them succeed in Afghanistan.

“That’s why we talk a lot about prioritizing our effort [between state and federal missions],” he said.

Other units haven’t been so lucky, however.

One of the Air National Guard’s Cyber Protection Teams assigned to the Texas Guard may be unable to meet its federal mission requirements due to collapsing retention associated with Operation Lone Star, the state’s massive involuntary state active duty mission currently guarding its border with Mexico.

Several of the unit’s troops are on the border “sitting at a watch point for hours on end with their thumbs up their ass doing nothing,” a member of the cyber unit told MilitaryTimes in January. Others are watching the issue-plagued mission unfold and are looking for a way to avoid getting called up for a second round of activations this fall.

That’s a difficult pill to swallow for highly skilled troops who tend to have lucrative civilian jobs — and who have one of the highest federal deployment rates in support of Cyber Command operations.

“[They] signed up for cyber warfare,” the unit member said. “If [they] wanted to do border patrol, [they] would’ve applied with Border Patrol.”

Keeping troops in

Leaked retention numbers for the Texas Army National Guard previously reported by Military Times also suggest that the organization may be seeing a drop in reenlistments.

Younger, and underemployed, Guard troops have been volunteering in greater numbers around the country for the COVID-19 response mission. Federal orders can be a tempting way to secure federal pay and benefits, which include the Post-9/11 G.I. Bill and other signature veterans benefits.

Overall, Guard leaders say that retention is strong, despite the high domestic usage rate.

The Army National Guard took the unusual step of halting its retention bonus program towards the end of fiscal 2021 due to sky-high retention rates and concerns over funding in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection response at the U.S. Capitol. Only Ohio and California did not meet their Army Guard retention goals.

Jensen, the Army Guard director, is still cognizant of the strain that this new era of Guard use could be having on employers and families — especially for mid-career troops.

“You look at our NCO ranks…They’re at the point in their life where their kids are at that age where they’re very active in school and extracurricular activities,” the general said. “They’re at that point of their civilian career where civilian employers [are] beginning to ask more and more of them, and we understand that competition.”

He explained that for part-time reservists, their relationship with operational tempo is a zero-sum game. You’re either at home with your civilian employer and family or you’re not.

“It’s a value proposition into the future…[we can’t] treat every single day as the most important day in the history of the [Guard],” he said. “We have to have an eye to the future, and we have to have an eye towards retaining our soldiers, our families, and our employers.”

A Band-Aid over bigger issues?

Another question that some commenters have asked is whether the Guard is merely acting as a bandage to temporarily alleviate deeper issues across American society.

When the New Mexico substitute teaching mission was announced, some pointed to low teacher pay — and even lower substitute pay — as being a root cause of the understaffing issues.

And those observers may have a point. Guard troops on state active duty orders in New Mexico receive at least the base pay and allowances of an E6: more than $125 a day, including reserve component housing allowance.

That’s more than the $13.33 hourly wage a typical substitute teacher makes on average in New Mexico, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Not all the substitutes are junior troops, either. One officer turned substitute teacher interviewed by the New York Times is a lieutenant colonel.

Regardless, politicians and community leaders alike are deeply thankful to have the Guard’s support.

“We’re grateful that the governor is recognizing this moment for what it is – a crisis,” said the state’s National Education Association chapter president, Mary Parr-Sanchez.

But Parr-Sanchez cautioned that a long-term solution to the issue would take time and “bold remedies” from electoral leaders.

“In the meantime, thank you Governor for doing whatever it takes to keep our schools going,” she said.

It remains to be seen how long that “meantime” will be for the New Mexico Guard and other states as the Easy Button era enters a third year.

This story contains reporting from the Associated Press.

The author of this article, Davis Winkie, is a member of NGAUS, which publishes National Guard Magazine.

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.