Does the Army know why junior officers leave? The discrepancy between two relevant studies suggests not.

Col. Everett Spain’s groundbreaking 2021 study, “The Battalion Commander Effect,” found that battalion commanders play a major role in determining whether lieutenants stay or leave the Army. Strangely, though, leadership did not even make the top-five reasons junior officers leave the Army in the Department of the Army Career Engagement Survey.

Implemented in 2020, the career engagement survey found that servicemembers, including junior officers, leave the Army primarily for family concerns. The survey identified the most important reasons for leaving the Army as: “Effects of deployments on my family/personal relationships,” “Impact of Army life on my significant other’s career plans/goals,” “Impact of Army life on family plans for children,” “The degree of stability/predictability of Army life,” and “Impact of military service on my family’s well-being.”

Struck by the disparity between “The Battalion Commander Effect” and the career engagement survey, I conducted an independent survey.

Survey Methodology

My survey’s population of interest was junior officers who plan to separate or recently separated from the Army.

I asked the following multiple-choice questions to determine whether the reasons for separation varied between certain demographics:

1. What is your rank?

2. What was your rank when you decided to separate from the Army?

3. Are you prior-enlisted?

4. What was your commissioning source?

5. What is/was your military service status?

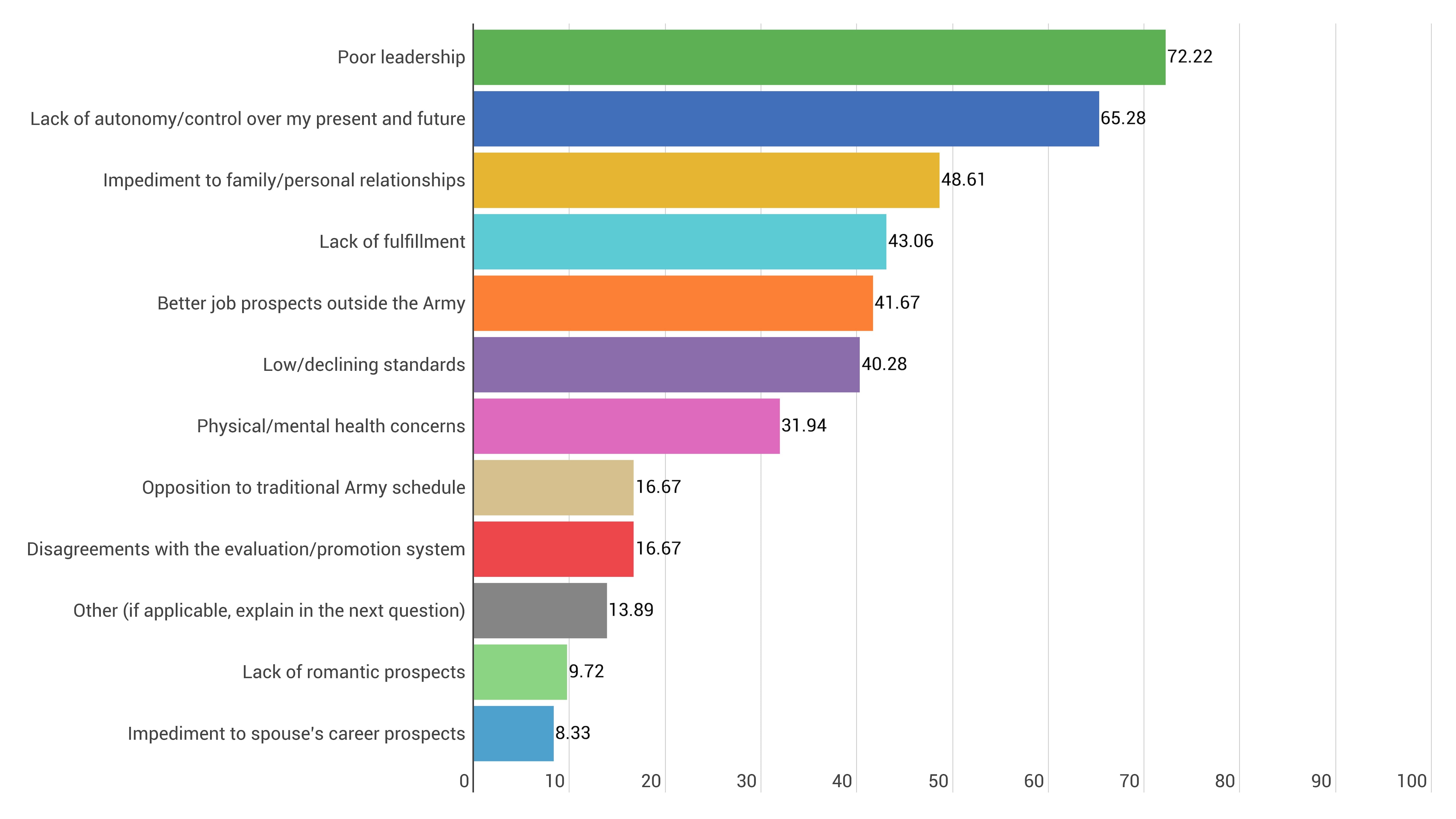

The next question asked respondents to select at most four reasons for leaving the Army:

6. -Impediment to family/personal relationships

-Impediment to spouse’s career prospects

-Lack of fulfillment

-Poor leadership

-Better job prospects outside the Army

-Opposition to traditional Army schedule

-Lack of romantic prospects

-Physical/mental health concerns

-Disagreements with the evaluation/promotion system

-Lack of autonomy/control over my present and future

-Low/declining standards

-Other (if applicable, explain in the next question)

In the spirit of open-mindedness, the final two questions were short answers:

7. If you answered “other” in the previous question, please list your reason.

8. Please expand on your reason(s) for leaving the Army.

When the survey closed, the final sample size was 523. Calculated at the 95% confidence level, the survey’s margin of error was 5%.

Limitations

I relied on social media to circulate the survey. Dissemination platforms included satirical military pages on Instagram, which could have resulted in sampling bias.

The survey overrepresented the United States Military Academy at West Point-commissioned and Officer Candidate School-commissioned officers, while slightly underrepresenting Reserve Officer Training Corps-commissioned officers. Accordingly, commissioning source variance may have skewed the results.

Finally, the survey vehicle did not rank respondents’ selections 1-4 based on the weight of their decision to separate. Therefore, results can only be interpreted by their recurrence, not their influence.

Results

More than 40% of respondents mentioned four of five reasons. In descending order, these were: “lack of autonomy/control over my present/future,” “poor leadership,” “better job prospects outside the Army,” “impediment to family/personal relationships,” and “lack of fulfillment.”

Notably, the commissioning source produced considerable variance.

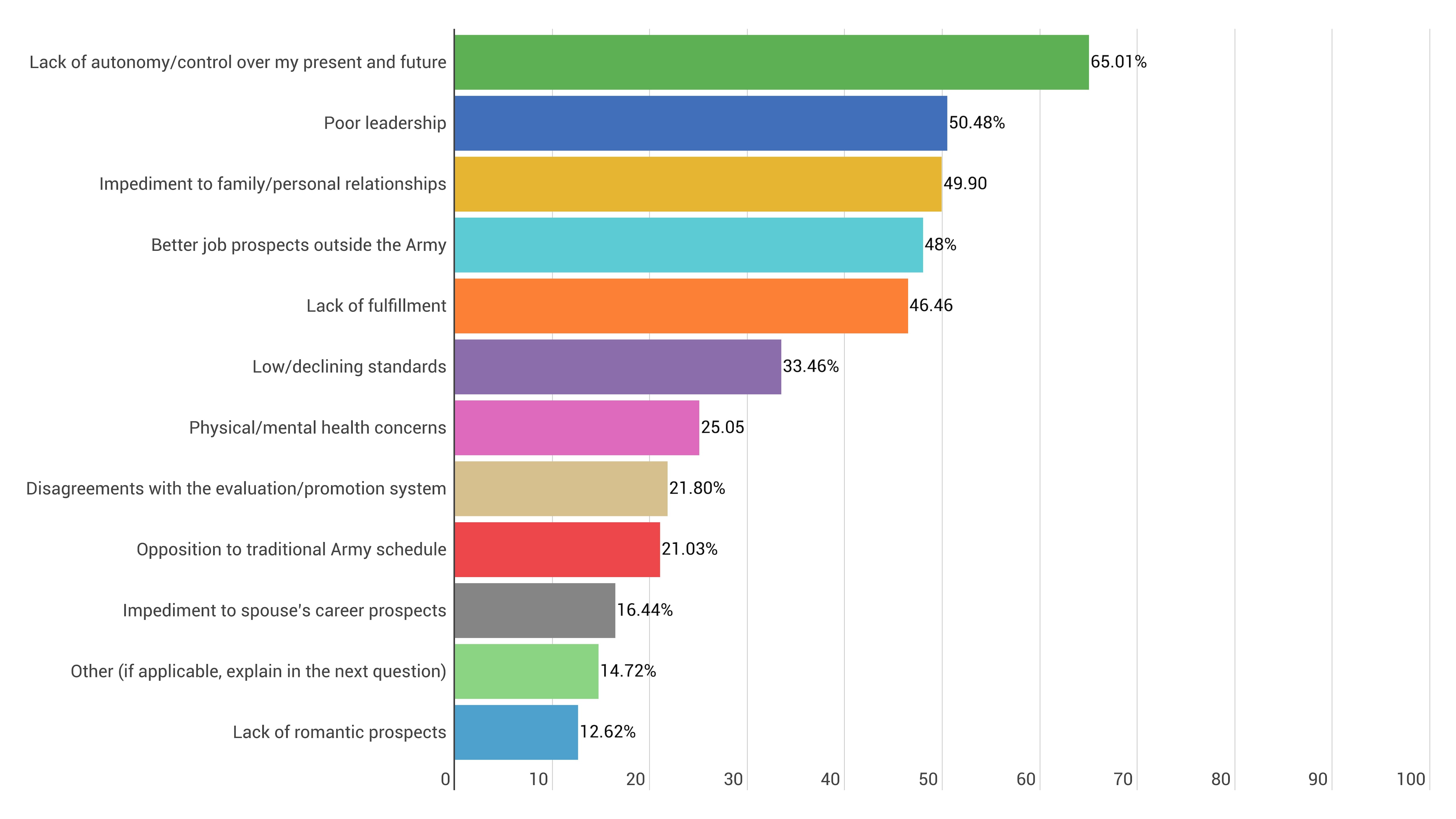

In descending order, ROTC-commissioned officers cited: “lack of autonomy/control over my present and future,” “impediment to family/personal relationships,” “poor leadership,” “better job prospects outside the Army,” and “lack of fulfillment.”

ROTC Reasons for Leaving the Army

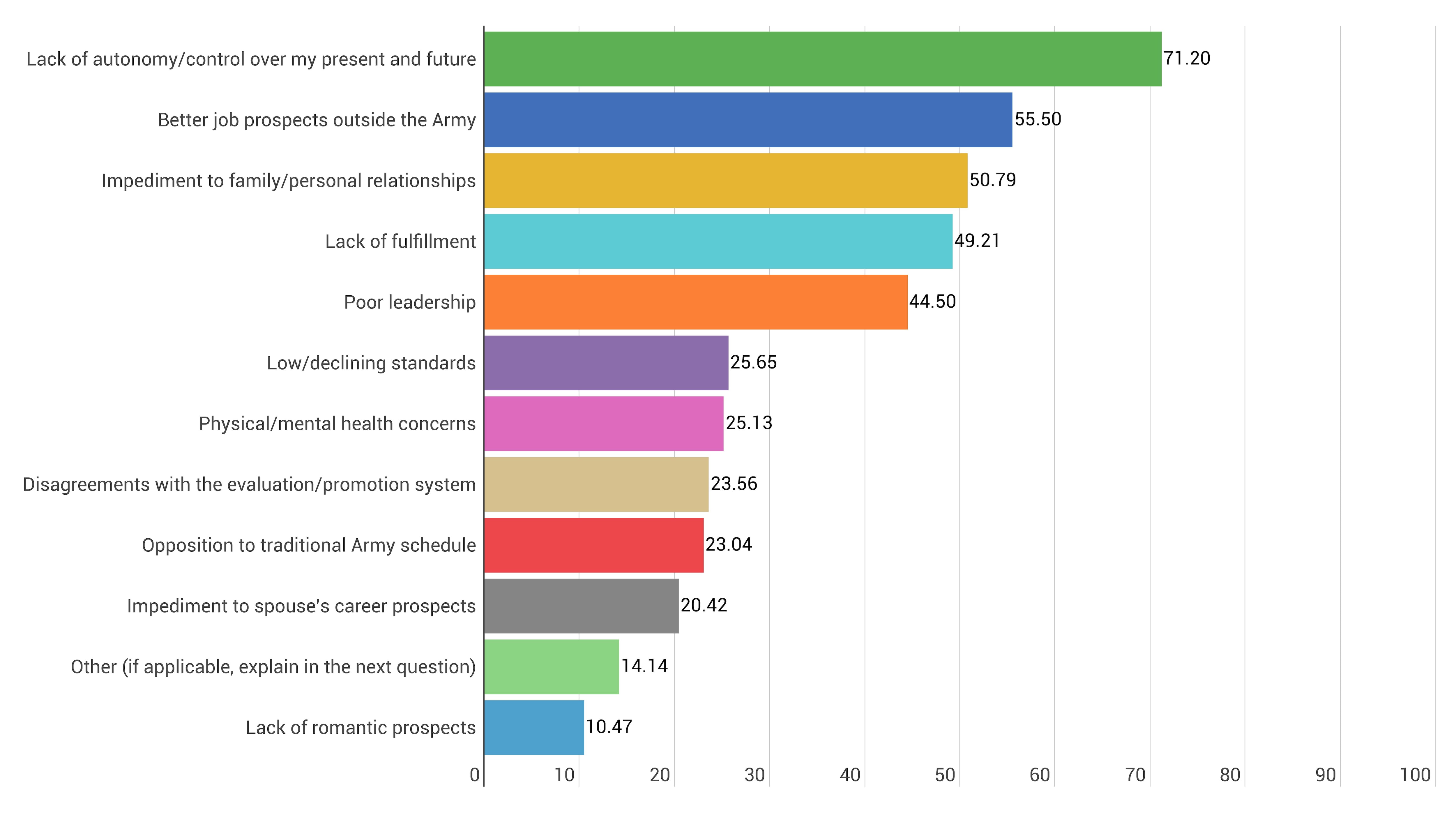

West Point-commissioned officers cited: “lack of autonomy/control over my present and future,” “better job prospects outside the Army,” “lack of fulfillment,” “impediment to family/personal relationships,” and “poor leadership.”

West Point Reasons for Leaving the Army

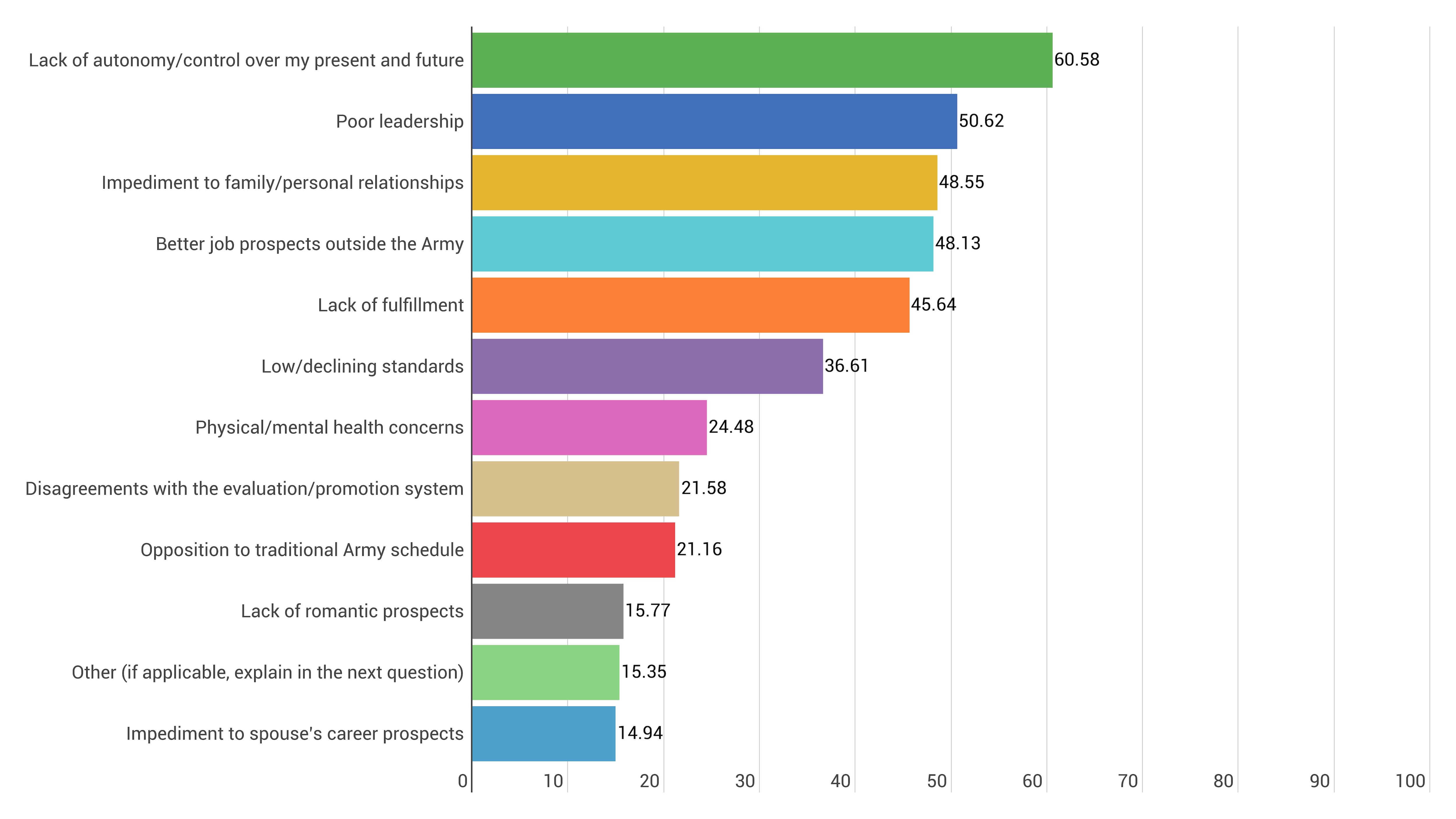

Finally, OCS-commissioned officers cited: “poor leadership,” “lack of autonomy/control over my present/future,” “impediment to family/personal relationships,” “lack of fulfillment,” and “better job prospects outside the Army.”

OCS Reasons for Leaving the Army

Discussion

The results demonstrate that while outgoing junior officers consider family concerns, other issues matter equally or more.

West Point officers cited civilian job prospects more often than their ROTC and OCS counterparts. Known for its robust alumni network, the school positions its graduates well to succeed beyond the Army.

On the other hand, poor leadership motivated OCS-commissioned officers more than any other population surveyed. Of note, prior-enlisted respondents – representing all three major commissioning sources – also mentioned poor leadership most. These officers were once soldiers. Presumably empathetic, the prior-enlisted officer is perhaps quickest to identify the battalion commander who does not care about the Joes.

The results make a strong case for leadership as a decisive variable in junior officers’ decision to leave the Army.

While more than half of respondents named “poor leadership” as a distinct reason for leaving, many also selected leadership correlates. Comments often directly associated leadership with “lack of autonomy/control,” and “lack of fulfillment,” the most cited and fifth-most cited reason, respectively. Respondents also related less cited reasons to leadership, like “disagreements with the evaluation/promotion system” and “low/declining standards.”

When describing their specific leadership concerns on the last question, whether as a distinct reason or correlated with another reason, respondents repeatedly mentioned sycophancy and toxicity. Frequent words included: “yes-man,” “toxic,” and variations of “hypocrisy” and “uncaring.”

Clearly, the desire for freedom lures many junior officers away from the Army. But a closely matched impetus is poor leadership.

Recommendations

Here, I offer two explanations for the disparity between my results and the career engagement survey, along with potential remedies.

Whereas I specifically surveyed junior officers who left the Army or planned to do so, the career engagement survey targeted all active-duty servicemembers. Including such a broad population likely skewed its results. To accurately determine the top reasons for leaving the Army, the career engagement survey should have only considered servicemembers planning to leave. Additionally, for more precision, future DACES should report results by paygrade

Relatedly, the career engagement survey likely faced a selection bias. Many people avoid voluntary tasks, especially when seemingly onerous. 89.1% of those invited to complete the career engagement survey ignored the 80-question survey. By reducing its questions, the career engagement survey could encourage participation in skeptical circles.

The second explanation concerns question wording. Out of nearly 80 questions, two mention leadership: “Brigade Commander or higher leaders’ handling of concerns about discrimination,” and “The mentorship I receive from my unit or organizational leadership.” An additional two mention “chain of command”: “Technical or tactical competence of my current chain of command,” and “Supportiveness of my current chain of command.” These questions only partly or indirectly address leadership. Future career engagement surveys should approach leadership more comprehensively.

Finally, the career engagement survey does not treat anticipated civilian employment opportunities as a reason to stay in or leave the Army. Instead, the study discusses civilian employment in an entirely separate section. This approach is flawed. The career engagement survey should assess civilian employment opportunities on the same five-point scale as it does the other questions.

The Army should recognize that civilian employment prospects lure many junior officers away from the profession. Senior leaders can contend with civilian employers. While the military may not realistically compete with corporate America’s salaries, leaders can address other facets of job satisfaction. For many officers vacating the Army for the private sector, organizational climate and career fulfillment matter more than money.

Hearing from hundreds of insightful, compassionate current and former junior offers, I witnessed firsthand the acute loss the Army is facing. Numerous respondents would have been great battalion and brigade commanders, perhaps even general officers. The Army could have retained many of them.

A toxic battalion commander does not simply jeopardize his unit during his tenure. He imperils the future of the entire organization.

The Army can fix its leadership problem. But it must first acknowledge that it has one.

Lindsay Gabow is an active-duty U.S. Army captain stationed at Fort Bragg. Her commentary reflects her own opinions and research and does not purport to speak in any official capacity for the U.S. Army. She is in the process of transitioning out of the Army to attend law school. For questions or comments about her survey, please feel free to reach out to her on LinkedIn or via email at lindsaygabow13@gmail.com.