This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to its newsletter.

When Kate Germano — a retired Marine who served for 20 years, including as the commanding officer of a training battalion at Parris Island, South Carolina — returned home from her stint working as an elections judge in 2020, she looked at her husband and said, “That was the most meaningful thing I’ve done as an adult citizen.”

Her husband, Joe Plenzler, also a retired Marine, had just joined the board of We the Veterans, a nonpartisan coalition of veterans and military families dedicated to increasing civic engagement among those who have served.

The organization was looking for a new initiative, and when Plenzler heard Germano say those words, he realized recruiting veterans to work as poll workers for the upcoming election could harness the energy of veterans looking for new ways to serve their country — while simultaneously strengthening the democratic system.

“Democracy runs on elections,” Plenzler says. “And elections run on volunteer poll workers.”

A War Horse investigation two weeks ago showed some veteran candidates on the ballot this November are exploiting the public’s trust of those who have served to push false narratives about voter fraud and election denialism. But other veterans are leading efforts to channel that trust and an ethos of service into pro-democracy initiatives, as well as to restore faith in elections and the democratic process.

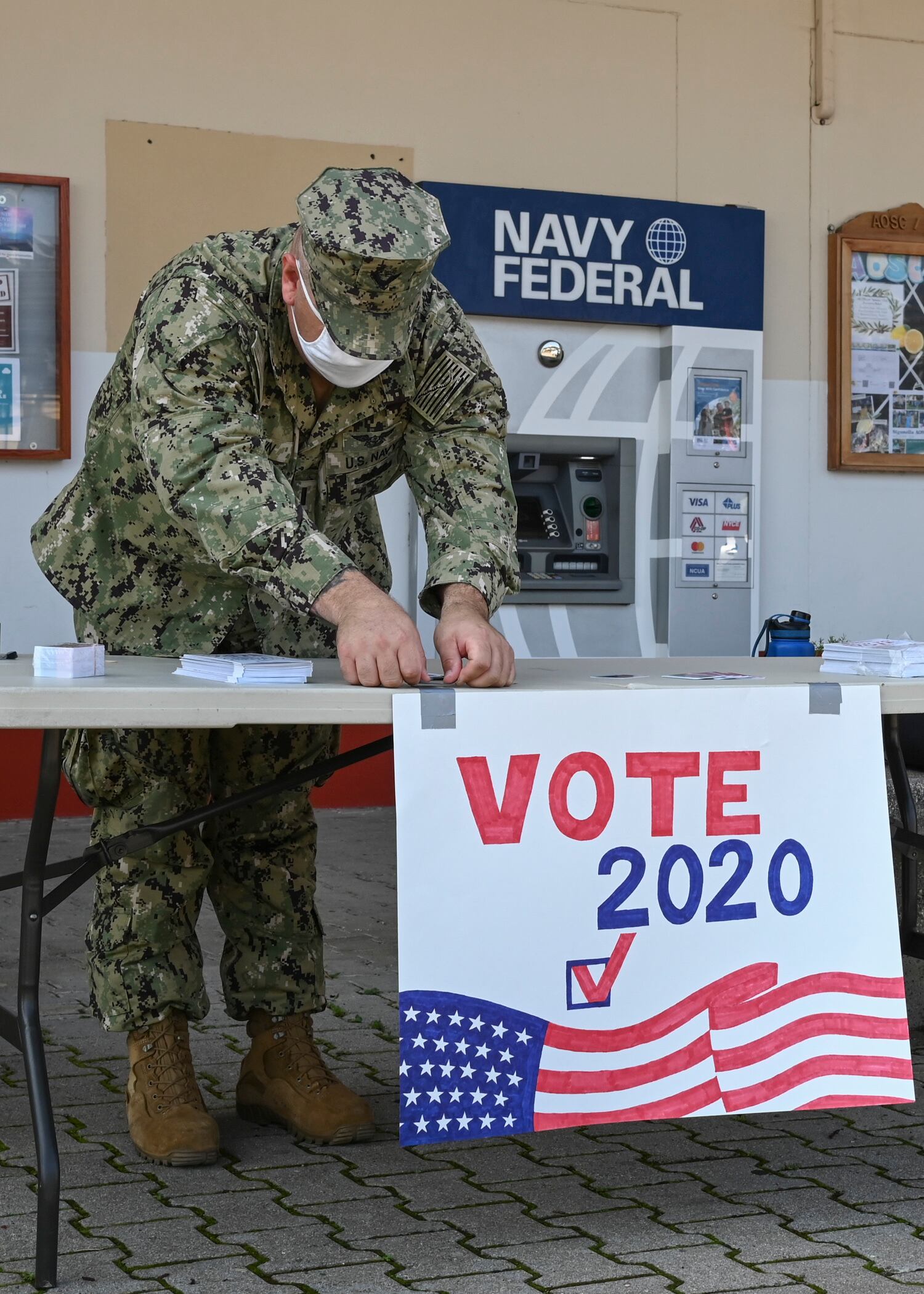

We the Veterans has recruited tens of thousands of veteran and military family poll workers to serve in their communities during the upcoming election. Other groups are raising awareness about the security of mail-in ballots and the military’s longtime reliance on them, as well as advocating for electoral changes to reduce polarization in the political process. Their members believe the voices of those who have served are critical in conversations about the country’s future, and that veterans, who swore an oath to uphold and defend the constitution, are in a unique position to continue that mission at a time when the constitution is under siege.

“This is civics,” Plenzler says. “It’s not politics.”

‘We’ve seen a lot of water under the keel’

Retired Navy Adm. Steve Abbot first worried about voting during the run-up to the 2020 elections, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged. Abbot retired from the Navy in 2000, after more than 30 years of service. He commanded the USS Theodore Roosevelt and later the Sixth Fleet. After he retired, he served as the deputy homeland security adviser to President George W. Bush.

As the 2020 election neared, Abbot watched as rumors surfaced about mail-in voting. Many states had expanded their mail-in ballot access because of the pandemic, and misinformation began to circulate about the security of this method of voting. “The military has long been dependent on being able to vote absentee,” Abbot says. As criticism of mail-in voting mounted, he grew concerned that troops’ ability to vote could be curtailed — or that service members would worry their votes might not be counted.

He wasn’t the only one. Abbot says he started to talk about his concerns with some of his peers — other retired four-star flag officers and former heads of service: Gen. Tony Zinni, a retired Marine who had served as the commander in chief of Central Command; Deborah Lee James, the former secretary of the Air Force; and Adm. James Loy, the former Coast Guard commandant.

“A few of us began to talk about whether it might be useful for some senior retired military and former service secretaries to come together to support the effort to ensure that the votes of active duty military were properly counted,” Abbot says. “It wasn’t just about Covid and mail service. It was a concern that there was disinformation, or at least misinformation, rampant about absentee ballots and the mailing of ballots.”

Those conversations resulted in Count Every Hero, a cross-partisan coalition of retired flag officers and former service secretaries dedicated to protecting troops’ right to vote and fighting misinformation about absentee voting.

“Those of us that have served in uniform for a long time have seen a lot of water under the keel, as we say in my business,” Abbot says.

The group threw the weight of their clear commitment to the country behind outreach efforts highlighting the military’s record of relying on mail-in ballots to ensure those in uniform can fulfill their civic duty to vote.

Soldiers have voted from afar since the American Revolution, when members of the Continental Army voted by proxy at town hall meetings. The first instance of widespread mail-in voting was during the Civil War, when nearly 150,000 Union soldiers submitted their ballots from the battlefield in 1864, leading to the reelection of Abraham Lincoln. Since then, service members have voted from far-flung locations in most elections — during World War II, military absentee ballots comprised nearly 7% of the votes cast in the 1944 presidential election.

Abbot says the group assumed they would disband or go dormant after the 2020 election. But when disinformation about the elections continued, they chose to expand instead.

“We think that the proper functioning of our democracy is a prerequisite for us to feel secure as a nation,” he says. “The peaceful transfer of power is a prerequisite for acceptable national security.”

Count Every Hero now has six principles it promotes, including ensuring equal access to the polls, securing elections from foreign interference, and building civic literacy among the voting public. The group helps connect people to resources about these topics and uses the reach of its high-ranking members to educate the public on the importance of free and fair elections.

Abbot practices what he preaches: “I think every citizen should feel an obligation to try to contribute to the country in the way that’s most appropriate for them,” he says. “I’m a newly enlisted poll worker, by the way, for my precinct here in Arlington, Virginia.”

‘We set up a big goal — then panicked’

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of election-day poll workers has fallen off precipitously. These positions, typically low or unpaid volunteer positions, are fundamental to the work of conducting democratic elections: setting up polling stations, issuing ballots to voters, and maintaining and transferring custody of voting materials. Historically, poll workers have been older — in part because Election Day is not a federal holiday, the ability to volunteer has often fallen to retirees — and many ceased volunteering during the pandemic because of health concerns.

On top of that, threats to poll workers and election officials skyrocketed as political tensions have risen and lies about the security and legitimacy of elections have proliferated. According to a survey conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice, one out of every six election workers has been threatened. One in three knows a poll worker who has left the job because of these threats or other safety concerns.

Taken together, the country is left with a dearth of poll workers — at least a 130,000-person shortfall, according to Plenzler’s group We the Veterans.

We the Veterans saw an opportunity. “Seventeen million vets,” Plenzler says. “If we can get a small number of them to volunteer, we can close that 130,000 gap in election poll workers.”

So the organization set out to do just that: recruit 100,000 veterans and family members to serve as poll workers in the four months that remained before election day.

“We set up this big, very audacious goal,” Plenzler says. “And then we started to panic.”

At first, recruitment was steady but slow. It grew as We the Veterans built a coalition of partners to help recruit poll workers, including the NFL, AMVETS, the Pat Tillman Foundation, and Count Every Hero. Then, in September, Veterans Affairs promoted the initiative, called Vet the Vote.

“Once that newsletter went out, within a few days we had like 34,000 people sign up,” Plenzler says.

The group has recruited more than 63,000 veterans and family members to work on election day. Plenzler says the 100,000 figure isn’t what matters. “We knew it would be a number that would grab people’s attention, because it’s big,” he says. “Can we do it? And if we can, awesome. If we fail to achieve that, at least we’ll have failed higher than some other groups.”

Veterans make for ideal poll workers, We the Veterans argues. “You’ve got to have a little bit of endurance to do it,” Plenzler says. Voting stations open early and close late. There are checklists and standard operating procedures. Poll workers assist harried and at times confused voters — and, increasingly, keep an eye out for threatening situations. “We have a security mindset,” Plenzler says. “We’re kind of trained on how to defuse a situation, so it doesn’t turn violent.”

And then there’s the sheer efficiency. Veterans often know how to enter an unknown situation and make things happen.

“You’ll never see a polling station set up faster or taken down faster than if two Marines are in charge,” Plenzler says.

‘We’re all incredibly dissatisfied with Congress’

Other groups have harnessed the power of veterans not just to strengthen the security of the elections, but to advocate for ideas that will help cool the political temperature nationwide, fighting against the polarization and rhetoric that has allowed misinformation, like that surrounding voting security, to proliferate.

“We’re all incredibly dissatisfied with Congress,” says Todd Connor, a Navy veteran. “We hate the two-party system. Even as we vote with our party, we don’t even like the parties that we’re voting for.”

Connor founded Bunker Labs, an incubator for veteran-led businesses, after he left the Navy. He’s been politically involved for a long time: following races, donating to political campaigns, running for local office. But in recent years, he started thinking about the problems underpinning his frustration with political trends he’d been seeing.

“I got to the point where I was like, OK, enough emotional exhaustion. What’s the answer?” he says.

Political polarization has deepened in recent years. Negative opinions about “the other” political party is increasing among Americans faster and more dramatically than in other democracies, according to research from the National Bureau of Economic Research. Studies show social media leads to the siloing of ideas and identities. This is particularly evident in primary elections, where fewer voters participate than in general elections — and those who do tend to be more extreme. This leads to only about 10% of the electorate casting votes in primaries that effectively decide the vast majority of congressional winners, according to Connor’s group.

“When you look at closed partisan primaries, the incentives are for people to act extreme,” Connor says. “That’s how you win a closed partisan primary.”

Last year, Connor founded Veterans for Political Innovation, a nonprofit that mobilizes veterans to advocate for political process changes to try to make elections less polarized and more competitive. In particular, the group pushes for open primaries, where all candidates run on one ballot, and voters may vote for any candidate, regardless of party.

Veterans for Political Innovation also advocates for ranked choice or approval voting. Ranked choice voting allows voters to vote for more than one candidate, ranked in order of preference. If a voter’s first choice is eliminated, their vote counts for their second choice, and so on. Similarly, approval voting allows voters to vote for as many candidates as they “approve” of, and the candidate with the most “approvals” wins.

Advocates for ranked-choice voting from both sides of the aisle say the format can help prevent extremism in politics and encourage more moderate candidates. Maine and Alaska recently adopted ranked-choice voting, and 56 cities and counties across the country use it. Nevada and cities in five states will vote this November on whether to adopt ranked-choice voting. Early research has found that the voting format leads to independent and third-party candidates doing better and may reduce legislative polarization.

“When you implement these reforms, more people vote,” Connor says. “You get more centrist representation. Voters prefer it of both parties overwhelmingly.” The problem, he says, is that it’s a message that needs a messenger. That’s where Connor sees veterans coming into play.

“Veterans are powerful messengers,” he says. “Who better to stand up and say, ‘Look, we ought to demand better’?”

This War Horse feature was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Sonner Kehrt is an investigative reporter at The War Horse, where she covers the military and climate change, misinformation, and gender. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, WIRED magazine, Inside Climate News, The Verge, and other publications.