The advice is deceptively simple: Eat better, get your exercise, sleep eight hours a night.

Some of the tips hark back to preschool: Have a regular bedtime, take naps, eat all your vegetables and drink your chocolate milk.

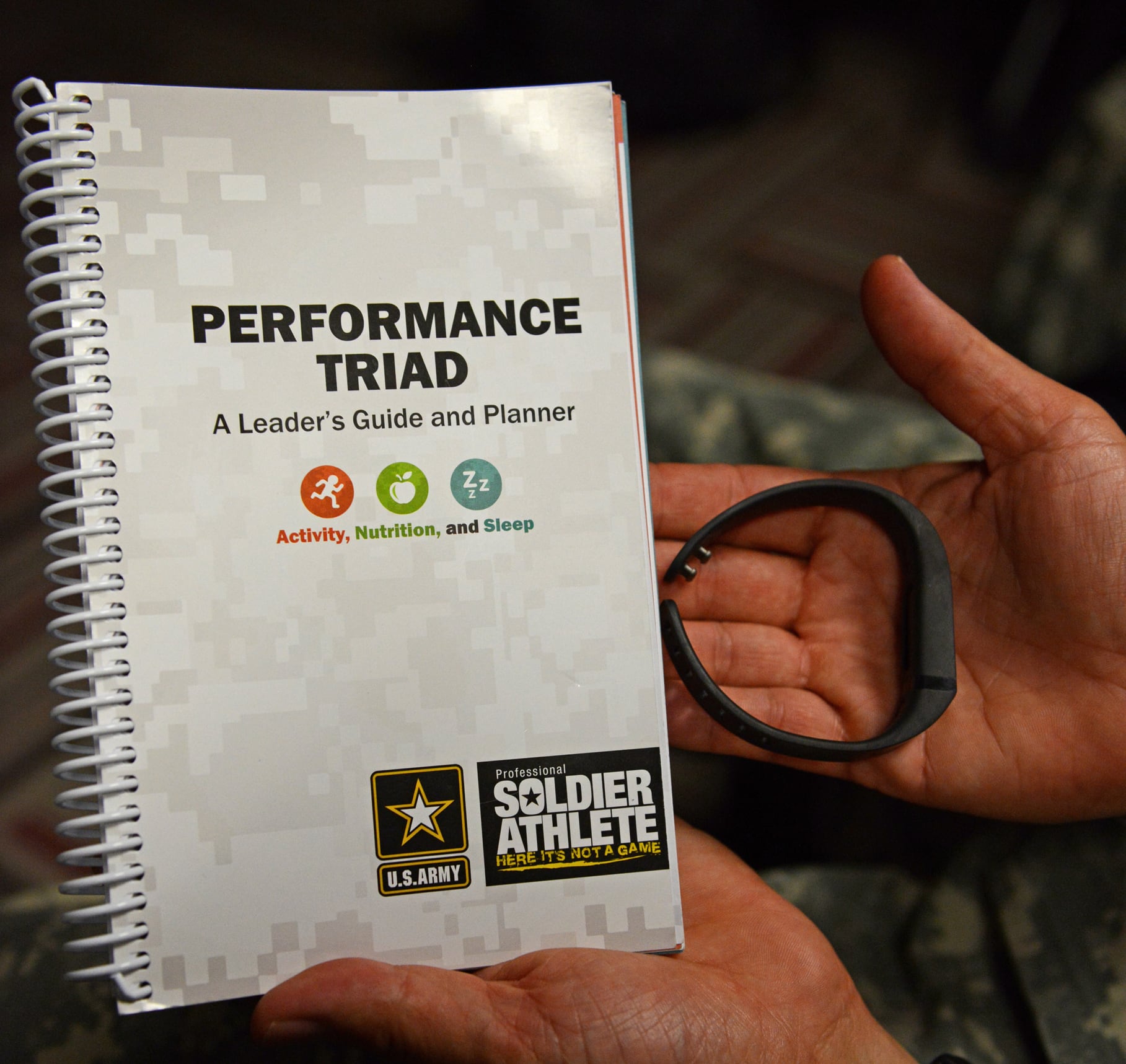

Most soldiers already understand the importance of healthy living, and there are multiple nutrition and fitness resources available to them beyond the ever-present unit PT. But officials behind the Performance Triad, an Army program that began with trial runs in three battalions in 2013, want more of them to appreciate the benefits they can realize by making healthier choices — benefits that would help improve overall Army readiness and can keep them in top shape long after leaving uniform.

Teyhen called the program's seven performance goals "aspirational," a conclusion backed up by findings from the first trial.

The Fitbit Flex device at right will help Soldiers keep track of their activity, nutrition and sleep.

Photo Credit: David Vergun/Army

'A lot of room to improve'

Participants in that trial wore monitoring devices to count their steps, took surveys on their diet and sleeping habits, and were tracked against the seven fitness goals presented by the program, broken into three categories:

- Sleep: Less than 5 percent of soldiers met the goals of eight hours of sleep in a 24-hour period and cutting off caffeine intake six hours before going to bed, according to figures provided by program officials.

- Nutrition: Less than 4 percent of soldiers met the goals of eating eight or more servings of fruits and/or vegetables daily, and refueling 30 to 60 minutes after strenuous exercise. "Most of our soldiers aren't doing those basic fundamentals," Teyhen said of the sleep and nutrition portions, "and so we still have a lot of room to improve."

- Activity: Soldiers performed better when asked to take at least 10,000 steps per day, engage in two or more days of resistance training per week, and get 150 or more minutes per week of moderate aerobic exercise. One battalion had more than 4 in 10 soldiers achieving those goals, and even the lowest-scoring unit had about a 29 percent completion rate.

Despite those relatively strong scores, exercise among soldiers in the six-month trial decreased as the study went on. Hard-chargers "regressed to the mean," Teyhen said, merely complying with the goals instead of exceeding them.

That led to the addition of "plus goals" for the program in time for this year's trials: An extra day of agility training and 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic exercise per week, plus 5,000 more steps per day.

While the goals were far from met, leaders of the units involved in the pilot program considered it a success.

Less than 5 percent of soldiers in the first Performance Triad trial met the goals of eight hours of sleep in a 24-hour period.

Photo Credit: Army

"This made a difference in our soldiers' lives downrange," Collins said. "I utilized it every day. I liked the app that they had. I used the education that I got on sleep, on eating, to discern how I could best utilize what I was given to maximize my health and fitness while deployed."

"The details provided by the program empowered leaders and subordinates to develop a plan of action to improve their overall fitness," said Burleson, now director of the Mission Command Center of Excellence at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, via email. "The use of the personal readiness device for each soldier to monitor their level of activity (steps taken), nutrition/weight, and sleep was well received."

The next step

Unit leaders are being trained on Triad methods at multiple locations in preparation for the September trial, Ryan said in an emailed response to questions. Participants include 44th Medical Brigade at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; 555th Engineer Brigade at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington; and other brigades based at Fort Carson; Fort Riley, Kansas; and Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Members of the Oregon National Guard and reservists with a combat support hospital unit, who received Triad training at Army Support Activity Fort Dix, New Jersey, also will participate, and trainers are "more formally engaging family members," Ryan said, encouraging them to take part in related fitness programs.

Active-duty participants will go through the Triad's 24 weeklong "soldier modules" — each with a different fitness focus — and two of the brigades will be issued wearable fitness devices "as a nudge toward behavior awareness and possible behavior change," Ryan said.

Field work

While still undergoing trials, the Performance Triad is far from the drawing board. Multiple Army websites list its goals and provide fitness resources, and it has an established social media presence — one likely to expand as the upcoming trial includes National Guard, reserve and dependent-outreach programs.

The in-unit programs allow Triad officials to get fitness boots on the ground: Trainers work directly with squad leaders to make them aware of available resources and help them find ways to work the program's message into their daily interactions with subordinates, instead of contributed to an already overcrowded training schedule.

A food service specialis at Fort Carson, Colo., ladles some vegetables. The Army is promoting better nutritional habits.

Photo Credit: Staff Sgt. Nancy Lugo/Army

"We tell them, 'This is not an Army program. This is something that you do already,'" said Sgt. 1st Class Darin Elkins, one of two primary Triad instructors and the noncommissioned officer in charge of the executive wellness program at the Sergeants Major Academy at Fort Bliss, Texas. "You already eat, you already sleep and you're already active. How do you take those three tenets and line them up so you're performing at the optimal level?"

Among the techniques:

Mission integration. It's not enough for leaders to understand the importance of sleep, Triad officials said — they need to incorporate it into their planning process.

"If I'm two weeks out from a sustained field exercise, as a leader, I should be telling my folks that they should be sleep-banking," Teyhen said. "Taking naps, getting a couple extra minutes of sleep each night, anything they can do to bank some sleep. ... Once they're in the exercise, I need to make sure they're using caffeine properly."

"Opportunist counseling." Elkins used the phrase to describe a squad leader interacting with his soldiers at the proper point of engagement, rather than in a training room with a PowerPoint presentation. Teyhen offered a tasty example.

"Chocolate milk is one of the best refueling fuels you can have 30 to 60 minutes after exercise," she said. "Instead of it being a lecture, at the end of PT, the squad leader says, 'Hey, folks, this week we're really going to focus on refueling after exercise. ...'"

The squad leader could solicit soldier testimonials in the coming days, showing the squad how proper post-workout nutrition paid off.

Treat like the elite. Soldiers have been very receptive to analogies involving, and tactics used by, professional athletes when it comes to fitness regimens, Teyhen said. Fitness buffs may be more likely to get the proper rest when they find out LeBron James sleeps 12 hours a day, and Tom Brady sacks out at 9 p.m.

"They really want to be Superman," she said, "and they want us to show them how to be Superman. The curriculum has changed to try to hit that mark a little better."

Break stereotypes, build knowledge. Collins talked about being "a meat and potatoes guy" before becoming fully aware of the benefits vegetables provided to his overall fitness. Teyhen said some soldiers didn't consider naps part of an overall sleep strategy; the program stresses that naps can be used to make up for lost rest at night, so long as they don't hinder one's ability to fall asleep at day's end.

Elkins said the program works to battle outdated, potentially dangerous fitness concepts — "you know, 'Sleep is a crutch. Water is a crutch.'" — that still exist in some parts of the service.

Expanded reach, without overkill

Along with a larger online component, the upcoming trial will involve more integration with existing fitness programs, including work with master fitness trainers and Army wellness centers. Program officials will assist dining facilities and shopettes with their offerings and expand the resources offered online and through the app.

"We're trying to synchronize programs across the Army, not create new programs," Teyhen said. "A lot of these tools exist, but people might not know how to access them."

Program officials are conscious of oversaturation, a line Collins said wasn't crossed during the first trial.

"You could go too far with this," he said. "You could make it so in-depth that it makes it harder to implement. ... I think they about had it right."

Collins and Burleson both said the program lent itself to spouse and family involvement, with household participation all but necessary to achieve some of the goals. Family readiness groups will be part of the upcoming trial, Teyhen said, as an important extension of a program that still revolves around a core mission.

"We train to fight," Elkins said. "How I prepare my mind, my body and my spirit to be at the optimal level, regardless of the circumstances ... I think that's what the Performance Triad, in essence, does. It gives soldiers the guide."

Kevin Lilley is the features editor of Military Times.