Mickael Cruz remembers that Christmas was a few weeks away. He remembers gathering in the gym before classes started at Marshall Elementary School. Another kid said something about an airplane crashing.

“It can’t be my dad because my dad comes home tomorrow. Not today, tomorrow,” the 8-year-old thought.

Over the loudspeakers a voice called him and his brother. A neighbor from housing where they lived on Fort Campbell, Kentucky, picked them up. When they got home she took them upstairs to their room. Downstairs it looked like a hurricane had gone through, things broken, people crying.

The neighbor tried to explain through her own tears.

“I didn’t understand. What’s going on? Where’s my dad?” Cruz kept thinking. “Then it hit me, my dad’s never coming back.”

The tragedy echoed across hundreds of homes as news reached them: 248 soldiers and eight crew members died in an airplane crash on Dec. 12, 1985 in Gander, Newfoundland, just as they took off on their final leg home from a six-month peacekeeping mission on the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt.

The crash was later ruled to have been an accident, likely caused by ice on the plane’s wings.

At a massive memorial service days after the crash, President Ronald Reagan reminded the mourners that their sons and daughters were not just warriors but peacemakers.

“They were there to protect life,” Reagan said.

The soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) were in the Sinai on a Multinational Force and Observers mission to prevent hostilities between Egypt and Israel, a result of the 1979 peace treaty between the two nations, brokered in part by President Jimmy Carter.

Lt. Col. Martin O’Donnell, public affairs officer for the 101st Airborne Division, served on the mission 15 years after the crash. He said the memory of the loss resonates today not only in Fort Campbell and nearby Hopkinsville but also at services at the MFO mission base in Sinai and in Gander, where the crash occurred.

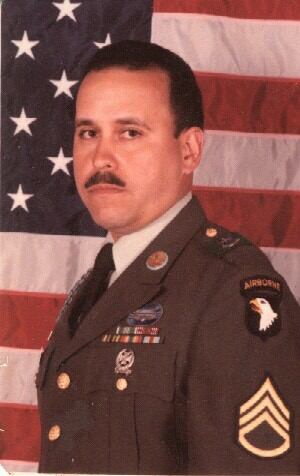

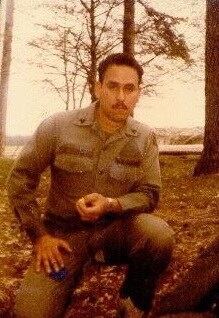

After the crash, the Cruz family moved back to Puerto Rico where Cruz’ father, Staff Sgt. Francisco Cruz Salgado, was raised. Fellow soldiers escorted Salgado’s remains to be buried in the Puerto Rico National Cemetery.

The years passed but memories did not fade. The young Cruz looked more like his father as he became a young man. He went to college and participated in the ROTC program. In 2000, he enlisted in the Army.

His mother nearly cried the first time she saw him in uniform.

Now, Cruz is a chief warrant officer 3 with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, and continuing a family tradition of serving.

They had not visited Fort Campbell since leaving so many years ago, so Cruz made a special route to travel to the post on his way from Fort Gordon, Georgia to Fort Riley, Kansas.

He pulled up to the front gate and asked the gate guard if he knew where the 101st Airborne Division museum was.

“It’s near those trees behind Burger King,” the guard said.

Cruz visited the museum, saw the artifacts of the famed “Screaming Eagles” and a section devoted to the single deadliest event in the history of the division. He learned that across the street, the trees the guard had referenced were planted in honor of those who perished in the crash.

Each had a plaque with the name of a soldier.

That tree and the black stone memorial wall facing the trees would become a place of returning for Cruz as he traveled through his Army career, rising in rank and accomplishments.

His father had been Air Assault qualified. So, in 2006 after he completed the school and got his “blood wings” he took them and pounded them into the tree.

He did the same again when he made staff sergeant, his father’s final rank.

Those emblems, and others, are still there.

He took his own son, Joshua, to the tree during the 30th anniversary commemoration. The Army has marked each anniversary of the crash since it happened 32 years ago.

Except for a three-year stint in Germany, Cruz has attended every memorial since he was finally stationed at Fort Campbell in 2005.

Though he has been back in Puerto Rico this past week checking on family members still recovering from Hurricane Maria, he will return in time for the ceremony on Tuesday.

“You have to honor those who’ve gone before us,” he said.

But more than the ritual observance of the tragedy, the memorial has offered Cruz and others ways to reconnect with memories of their friends and families.

Around this time each year, he’ll see a new online message or hear from someone who knew his father.

“I knew him as dad. I did not know him as a soldier, leader,” Cruz said.

Ira Richardson, a retired major who served with the unit as a staff officer at the time of the crash, told Army Times that many of the unmarried soldiers slated for seats on the first plane gave up their seats to married soldiers to get home for the holidays.

“That doubled the tragedy of the crash because everybody had a family,” Richardson told Army Times at the 30th anniversary.

As many years have passed as Cruz’ father lived – 32. Despite the tragedy, Cruz chose to continue a family legacy of grandfathers who served careers in the Army and the National Guard and a father who lost his life in service.

Cruz uses the anniversaries to remember his father, look at old pictures and movies, tell stories.

Each day he puts on the uniform, he remembers the man he lost so young. And he sees his work as continuing that man’s legacy.

“I did it because of him,” Cruz said. “To make him proud of me.”

Todd South has written about crime, courts, government and the military for multiple publications since 2004 and was named a 2014 Pulitzer finalist for a co-written project on witness intimidation. Todd is a Marine veteran of the Iraq War.