Editor’s note: In the original version of this story, a source stated that Del Barba is in care at Brooke Army Medical Center. Army Times has since confirmed that he is a patient at the Institute of Surgical Research at Joint Base San Antonio, Texas.

On Feb. 21, Fort Benning, Georgia, announced that it was dealing with a small cluster of trainees who had come down with strep. Everyone affected had been treated, the statement said ― mostly some infected tonsils ― and as a precaution, all trainees and cadre at the Maneuver Center of Excellence would be receiving preventive doses of antibiotics.

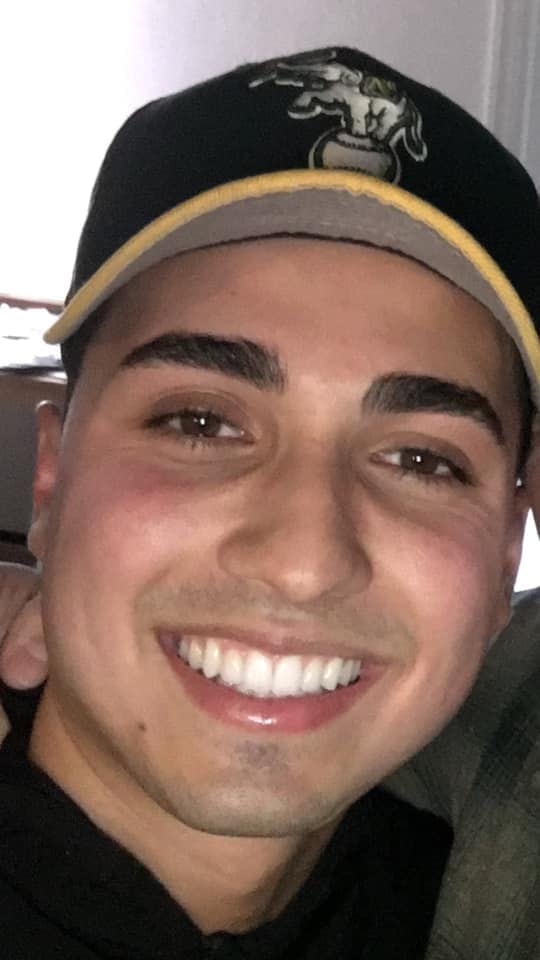

Meanwhile, in San Antonio, one of those trainees had just taken his first bites of solid food in nine days, as he recovered from a flesh-eating form of strep that had required amputation of half of his left leg. Pfc. Dez Del Barba is still recovering at Brooke Army Medical Center after multiple surgeries.

For the first time, representatives from Fort Benning are acknowledging that a soldier was hospitalized as a result of the outbreak. Specifically, on a ventilator until doctors could tackle the infection that almost killed him. He’ll remain in care until he’s fully recovered, his Army career traumatically ended before it really began.

At the same time, military families have been making inroads in the effort to overturn the Feres Doctrine, the law that prevents service members from suing the Defense Department for illness or injury suffered while on active duty, regardless of clear medical malpractice.

An investigation will determine whether Fort Benning officials face repercussions for their handling of the outbreak, but the soldier’s family is speaking out now.

“I cannot fight the Army. The Army’s too big,” a member of his family told Army Times on March 23, requesting anonymity to discuss Del Barba’s case. “But I want people to know the truth.”

Del Barba, 21, reported to one-station unit training in early January. The Stockton, California, native had taken a leave of absence during what would have been his last semester at Sonoma State University, to complete basic training, then go on to officer candidate school and earn a commission in the California National Guard.

Today, he is a patient BAMC, at Joint Base San Antonio, Texas, where he is recovering from the necrotizing fasciitis that took his leg, as well as extensive skin grafts to replace damaged tissue. The plan is that he’ll be fitted for a prosthesis and finish his degree when this is all over, but for now, no one knows when that might be.

“Our thoughts and concerns are with our soldier, who is currently hospitalized, and his family during this trying time,” Ben Garrett, a Fort Benning spokesman, told Army Times in an April 2 statement, though he could not confirm the soldier’s identity, citing privacy issues. “Our soldiers are our most important asset and we will make every effort to ensure they receive the best medical care the U.S. Army provides.”

Members of Del Barba’s family have spoken to local media about their ordeal, while keeping a meticulous diary of his recovery on Facebook.

They feel that the Army dropped the ball on diagnosing and catching Del Barba’s illness, then downplayed the number of soldiers affected and swept his case under the rug when Fort Benning went public about the outbreak.

“One of the medical professionals from Fort Benning came right here where I’m standing in the hospital, told us to our faces, with his two senior [noncommissioned officers], that there were 56,” the family member told Army Times. “That was day two of Dez being in the hospital.”

‘Not an epidemic’

Two months ago, there was little information coming out of Fort Benning. Rumors were flying at the post, home to the Army’s infantry and armor initial entry training enterprise.

“Was it hundreds of positive strep cases, or just a handful? Did someone actually die? And why am I lining up for antibiotics if I feel fine?” soldiers wondered.

And then there was the trainee who died on Jan. 22. Pvt. Christopher Wellington’s cause of death is protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, or HIPAA, Garrett said.

It all started in mid-January, when three trainees came down with Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections. According to the National Institutes of Health, the bacteria ― commonly referred to as Group A strep ― is a common cause of tonsillopharyngitis, what you probably know as strep throat.

But it can also cause more life-threatening infections, from pneumonia to meningitis and infections of the skin and soft tissue ― like necrotizing fasciitis (pronounced neck-roh-ty-zing fash-ee-eye-tiss).

A fourth trainee was diagnosed with a tonsil infection, but came back negative for strep.

“In an effort to ensure the health and readiness of the force, Fort Benning spared no expense in its aggressive response to address the Group A Streptococcus concern,” Garrett said in a March 29 statement to Army Times. “By the end of February, treatment had been initiated for Fort Benning’s entire basic training population of nearly 10,000. The efforts thus far have vastly reduced any concern for future cases of A Streptococcus.”

Members of those soldiers’ units were screened for strep first, the statement said. Though there were few symptomatic soldiers, many of them were found to be carrying the bacteria. About 140 were tested in January, and more than a thousand additional were tested in February.

The sick soldiers were never placed in any sort of medical isolation or quarantine, Garrett said, as it’s not necessary for this strain of strep.

“What is important is that the sick are segregated from the healthy,” he said. “This can be accomplished in the same bay, as long as there is adequate space available.”

The key is to contain the spread of droplets projected by coughing, for example, with good respiratory and hand hygiene.

“It is not necessary to segregate trainees without symptoms, even if they happen to screen positive for Group A strep,” Garrett added. “Carriers of Group A strep ― that is, trainees who are NOT exhibiting any symptoms ― are not at significant risk of transmitting Group A strep to others and do not need to be segregated from other trainees.”

And in this instance, Garrett said, no trainees were segregated, even within their bays.

In total, according to Army Training and Doctrine Command, 61 soldiers were both symptomatic and positive for strep. To knock out any nascent infections, about 10,000 trainees and cadre were treated ― penicillin shots for the positive cultures and four 500 mg doses of azithromycin ― commonly known as a Z-Pack ― for everyone else.

Those treatments finished on March 15, Garrett said.

“Out of an abundance of caution, as a preventive measure the command directed, that all trainees arriving since that time receive a bicillin injection upon arrival at the reception station,” he added.

Bicillin, a powerful antibiotic, can treat infections as serious as syphilis and tetanus, but it is also effective at preventing strep.

And in the mean time, authorities with Fort Benning’s Martin Army Community Hospital have launched an investigation into how medical staff handled the outbreak, Garrett confirmed.

“#DEZSTRONG”

Del Barba’s symptoms first appeared in early February, his family member said, but not in a place where medical staff would have lumped him in with the strep outbreak.

“Dez went to seek help on the fifth of February,” she said. “He went for his knees. He didn’t know that it was [also] his throat.”

The soldier had been complaining of leg pain for several days at that point, she added, but had been discouraged from going to sick call by his drill sergeants.

“ ‘March forward soldier,’ ” the family member said, recounting Del Barba’s description of his drill sergeants. “ ‘If you go to sick call, you’re going to be recycled.’ The fear of being recycled is embedded in all of these trainees’ heads.”

That response is not part of policy, according to Fort Benning.

“When concerns about the medical care provided in the training environment are brought to the leadership’s attention, the command partners with Army Medicine to ensure those concerns are being appropriately addressed,” Garrett said in his statement, confirming that commands are investigating whether trainees were discouraged from seeking treatment.

Anecdotally, it’s not uncommon for cadre to encourage soldiers to push through discomfort. Basic training is hard on the body, and normal aches and pains are expected.

“And there are soldiers, every day, who complain and there’s nothing wrong with them,” the Del Barba family member said. “But they have to differentiate between a consistent malingerer and, this is a soldier with a legitimate medical issue.”

Del Barba did have a legitimate medical issue, but it wasn’t with his knees, according to medical records.

On Feb. 7, complaining of a sore throat, he went to medical for a throat culture. The following day, he went back to deal with his knees, and staff recommended he report for physical therapy to address what was determined to be a very common overuse injury.

That same day, his throat culture came back positive for strep. It was a Thursday. A handwritten note in his medical records reads, “Call Monday AM. Positive strep throat,” according to the family member.

“So what is Fort Benning’s procedure when somebody comes up positive?” she said.

It should have been an almost immediate notification, according to Lt. Col. Michael Superior, chief the Army Public Health Center’s disease epidemiology division.

“The Army’s goal is to ensure any positive strep culture results are followed up and treated appropriately without unnecessary delays in care,” he told Army Times in a March 29 statement. “A trainee’s leadership is usually notified the same day of a positive result.”

But that didn’t happen.

“On Feb. 10, there were soldiers who were massaging his legs while the drill sergeants were nowhere to be found,” the family member said, trying to relieve some of his pain and swelling.

He went to sick call again that day, she added, but the provider didn’t check his records ― which would have indicated he had tested positive for strep.

“Acute care clinics and especially emergency departments are usually focused on the primary purpose for the current visit,” Superior said. “A trainee’s past medical history will still be discussed, however. If there is something relevant to the purpose of the current visit, it should be reviewed in the medical record.”

It’s possible that the provider would not have drawn a parallel between the sore knees and the sore throat.

“This is particularly true if the trainee reports having sought treatment recently for the same condition,” Superior said of the focus on the body part in question. “For example, if a trainee has leg pain, he/she may be asked if it is the first visit related to the leg pain. Medical records would be reviewed for any documentation related to the current condition.”

RELATED

On Feb. 11, when medical indicated they would call his command, Del Barba collapsed trying to get out of his bunk in the middle of the night.

After being evaluated at Benning Martin Army Community Hospital on post, he was rushed to a local Columbus, Georgia, hospital, then flown the University of Alabama’s burn care unit in Mobile once stabilized, on Feb. 13. There, doctors worked to stop the infection’s spread while Del Barba, unconscious, breathed with the help of a ventilator.

His lower left leg was amputated on Feb. 14, and two days later, he and his family were flown to BAMC. There he was again able to breathe on his own, but recovery has meant physical therapy to repair his atrophied muscles, and harvesting most of the skin on his chest and back for skin grafts on his legs ― 16 surgeries and counting.

“He’s in so much pain that that is nothing compared to what he’s going through today,” the family member said of the initial infection, comparing it to how sore and delicate most of his skin is now, as the graft sites heal.

Army officials have visited to offer their support, she added, but they mostly leave a bad taste in the family’s mouth — a challenge coin does not make it better, she said.

“If they don’t come to his room again, I’ll be happy,” she said.

On the other hand, she added, the hospital itself has been a saving grace. Del Barba will rehabilitate at BAMC’s Center for the Intrepid, best known for treating soldiers recovering from severe burns or amputations sustained in combat.

“The only silver lining in this whole entire mess is BAMC,” she said. “BAMC has been nothing but top-notch medical care for Dez.”

The family is looking into enrolling him at the University of Texas at San Antonio, she said, so he can finish school and recover possibly at the same time. Once he is healed and he has completed rehabilitation with a prosthetic leg, the expectation is he’ll be medically discharged.

“He wants to go back home, of course,” she said. “I can’t put a time frame on it.”

The Del Barbas are a military family. He was following his mother, who retired after 23 years of service, into the California Guard. Do they regret his enlistment?

“Not at all. I don’t blame the Army. I blame the people who took care of him,” the family member said. “They took an oath. I blame the leadership for not checking up on their soldiers.”

At this point, she added, the family isn’t considering legal action, whether Feres is overturned in the future or not.

And she hopes sharing his story might result in some change at basic training, when it comes to taking care of sick soldiers.

“I know it’s not going to happen soon, but maybe 15, 20 years from now,” she said. “Who knows?”

His next surgery is scheduled for April 8.

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.