The Army has been seeing increased retention since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, decreased end-strength under the latest budget request, an end to the Global War on Terror, a need to make better staff sergeants, mandatory lateral appointments to corporal, and a new competition and selection processes for key senior enlisted leader positions.

Those factors are just some of the reasons why the path to promotion may be slowing and narrowing for some enlisted troops across the force. But the Army says this is an effect of a new approach to talent management that’s focused on getting the right soldier in the right assignment at the right time.

To get the full picture, Army Times reviewed and compared promotion data to prior years, researched Army policies and spoke with leaders about the intent behind the changes.

Simply put, the Army is in “a war for talent,” as Sgt. Maj. Mark Clark, the deputy chief of staff G-1 senior enlisted leader, phrased it in a phone interview with Army Times.

“So as we compete with our sister services and corporate America to acquire and retain the best talent, we have to evolve our policies in order to set a culture that enables our ability to develop and employ [our talent],” Clark said.

Fewer NCO promotions?

When measured against its goals, the Army is doing an excellent job with enlisted retention.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the COVID-19 pandemic, the regular Army secured 1,693 more reenlistments in fiscal year 2020 than the previous year, achieving 53,024 against a goal of 50,219.

Increases to retention can slow promotions by creating more competition for a limited number of positions.

And the number of positions is holding steady or shrinking, as the Biden administration has asked the active-duty Army to slim down to 485,000 troops in 2022.

Another factor affecting NCO promotions could be the Army switching to an order of merit promotion system for senior NCOs that selects the best-qualified soldiers from the list for promotion, but only as vacancies arise on a monthly basis. Before, the Army would consider senior NCOs for promotion all at once during annual selection boards.

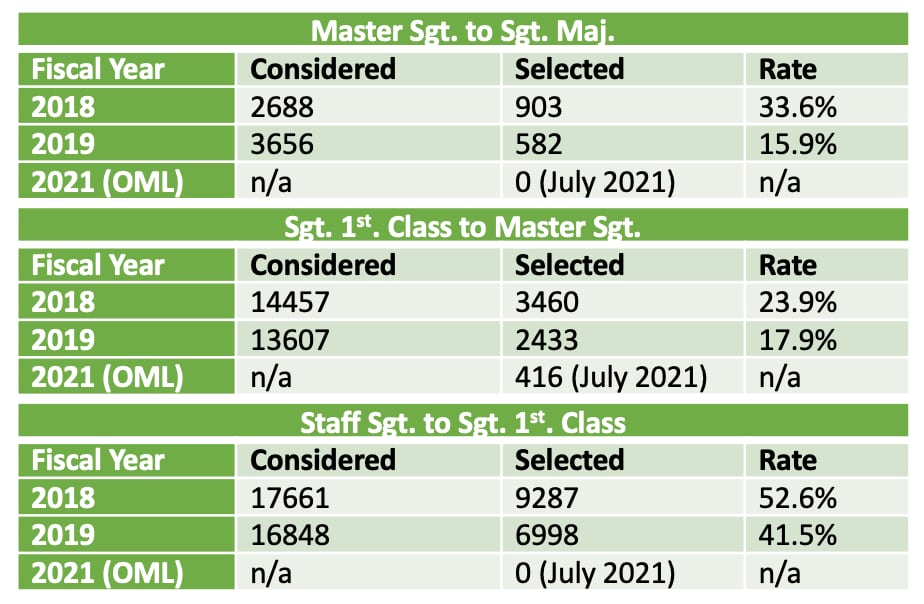

Whatever the reason, the promotion squeeze is already here for senior NCOs.

As of mid-July, the Army was still yet to promote a new sergeant first class or sergeant major from the new OML system due to a backlog of promotable NCOs selected by the final selection boards held in fiscal 2019.

Those backlogs are nearly resolved, though, and promotions will be exclusively based on the OML beginning Sept. 1 for sergeants first class and Oct. 1 for master sergeants.

Clark says the delay in getting soldiers from the OML system promoted is because of a “fundamental change in the promotion process.”

Previously, NCOs would first be selected for promotion and then complete their required training to go to the next rank. The guiding acronym — STEP — stood for “select for promotion, train, educate, then promote.”

But now, the OML is used to select soldiers for training before NCOs are locked in for promotion as the Army requires — STEP is now “select for training, train, educate, then promote.”

Clark says the Army has completed its final training backlogs from the old promotion system, but it’s too early to tell whether promotion rates will rebound in the face of strong retention and contracting end strength.

Slowing it down

One thing is certain: Clark and the Army want to build more experienced NCOs from the ground up.

Clark says the changes are meant to better prepare junior NCOs for the increased responsibilities they’ll someday have as platoon sergeants and beyond once they become senior NCOs later in their career.

The shift begins at the lowest rung of the NCO ladder, with an Army directive signed in May ordering the active-duty Army and Army Reserve to appoint as corporals all specialists who are fully promotable to sergeant. This means that they have been recommended by a unit board for promotion and have completed the month-long Basic Leader Course.

Before the change, lateral appointments to corporal were permitted for specialists selected for promotion to sergeant regardless of whether they’d completed BLC, but only if they were serving in a position that required an NCO.

Clark said the old policy presented “some risk,” because “we’d have [corporals] promoted who are not trained, taking leadership positions.”

He emphasized the importance of linking a new NCO’s training status with the “visible difference” of wearing corporal’s stripes, though they still receive the same pay as their specialist counterparts.

“The Corporal initiative is designed to create a positive, visible welcome to the NCO Corps for Soldiers that have proved themselves ready,” said Sergeant Major of the Army Michael Grinston in a tweet celebrating the new NCOs.

“Now that we’ve given them the tools [training and education] of an NCO, they can begin to perform those duties,” Clark said. He also noted that the new policy allows corporals to receive increased “leader development time” and receive formal feedback and performance ratings via the Army’s NCO evaluation reporting system.

Clark described the corporal initiative as just the most recent step in implementing a new junior leader development program.

Soon, hopeful NCOs will have to demonstrate proficiency in “their warrior tasks and individual battle drills” before being selected by unit boards for Basic Leader Course and eventual promotion, Clark said. “The program…is being codified and developed by [Army Training and Doctrine Command] right now.”

Clark also pointed to recently-implemented mandatory questions for unit promotion boards that include “situational leadership” questions designed to evaluate a potential NCO’s ability to “help us get after some of the counterproductive behaviors that are plaguing our ranks such as [sexual harassment and assault] and suicide.”

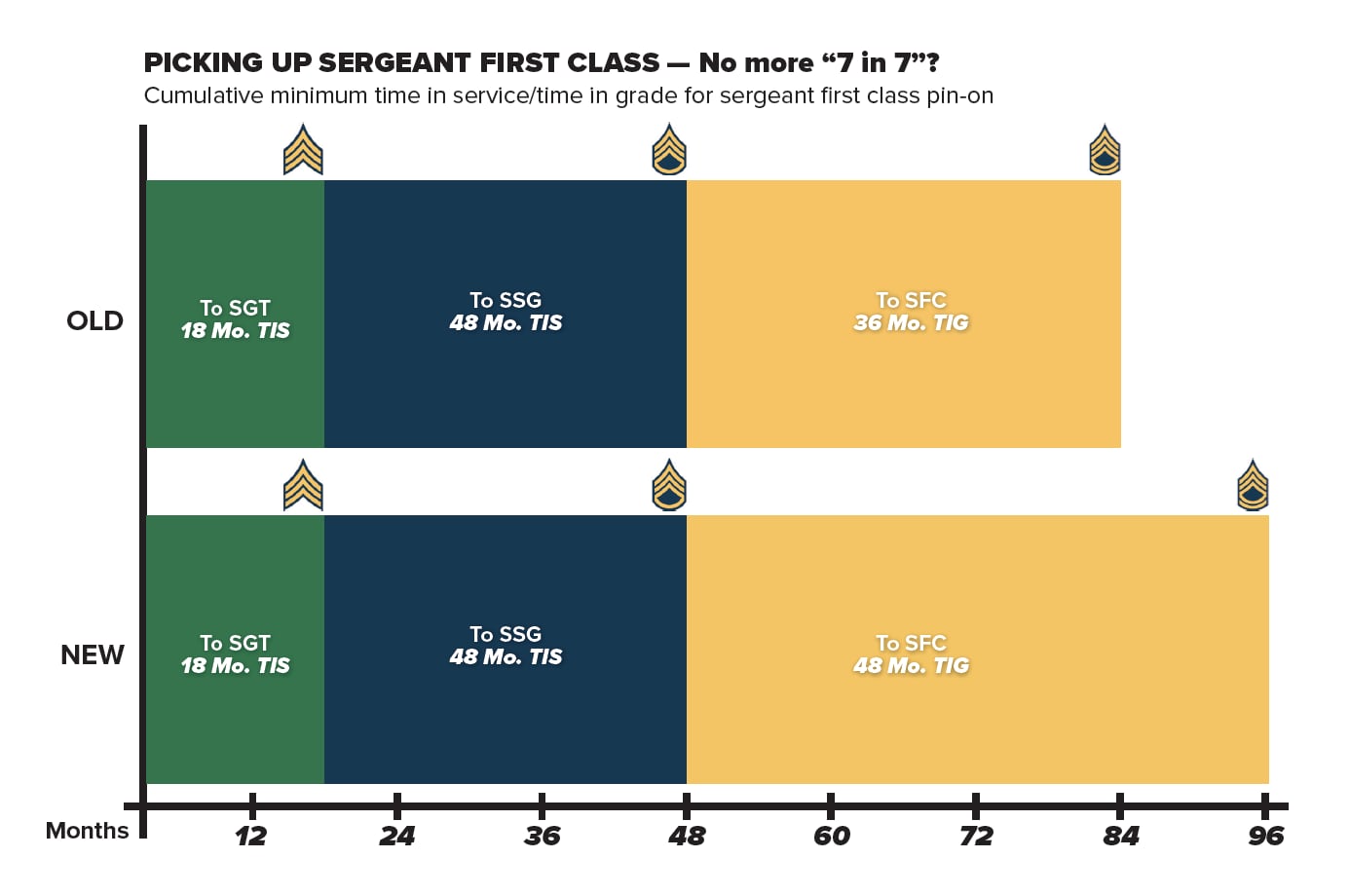

The Army is also trying to improve the quality of soldiers’ day-to-day lives and improve the quality of future senior NCOs by making staff sergeants wait an additional year before promoting to sergeant first class. That change is effective beginning with the fiscal 2021 OML evaluation boards.

Now, staff sergeants not in a special operations career field must serve 48 months time-in-grade before they can promote, an increase of 12 months. Green Berets, civil affairs and psychological operations staff sergeants saw their time-in-grade requirement increase from 24 to 36 months.

Purportedly gone are the days of “E7 in 7 years,” where promising performers would be rushed through the ranks. Under the new regime, the fastest an NCO can make sergeant first class will be on the first day of their eighth year in service, with the exception of special operations forces.

SMA Grinston discussed the initiative on Twitter in May.

“The ultimate goal,” as he put it, is to “build a better staff sergeant.”

“For the majority of Soldiers, that is THE most critical position in the Army,” Grinston said to someone asking about the goal of the policy change. “I need you to have time to serve in critical leadership positions (squad/section leader) AND broaden [as a drill sergeant or recruiter]. 58,000 SSGs lead 58 percent of the Army.”

The old time-in-grade requirement sometimes didn’t give staff sergeants enough experience to succeed as a senior NCO, according to Clark.

The Army frequently selects staff sergeants — sometimes involuntarily — to spend up to three years as recruiters or drill sergeants.

“Staff sergeants are the NCO grade that has the most demand,” Clark explained.

And while broadening assignments are important to an NCO’s development, he said, “many of them did not have the opportunity to serve in a key developmental position that would truly qualify them for the next higher grade.”

Clark pointed to the pre-change experience of infantry staff sergeants as a prime example of that effect.

An infantry sergeant often spends his or her time as a team leader, in charge of four soldiers. For infantry staff sergeants, the goal is to serve as a squad leader, where they supervise nine soldiers and operate with much greater autonomy.

Squad leader time prepares NCOs to become platoon sergeants upon promotion to sergeant first class, where they will be the senior NCO among 39 soldiers and responsible for mentoring the platoon leader.

“But if [an infantry staff sergeant is] serving as a drill sergeant or a recruiter, they typically miss that opportunity to serve as a squad leader, and may be promoted to sergeant first class, and then come back to the operational Army as a platoon sergeant without the experience of having been a squad leader,” Clark said.

And NCOs who went straight from managing four soldiers to nearly 40 — especially after spending three years away from the line as a drill sergeant or a recruiter — frequently would not perform to their potential, he explained.

Grinston pointed out the second order effects of this phenomenon, as well, on Twitter.

“If you go to be a recruiter and get promoted and become a platoon sergeant without having grown as a squad leader, your experienced squad leaders may lose confidence and that sets us back in different ways,” the Army’s top NCO said.

The overall goal of all the promotion changes, Clark explained, is to build a pipeline of stronger, more experienced NCOs into the senior NCO talent pool.

Senior NCO shifts

The Army is also implementing new selection and assessment programs that will also change how the service screens senior NCOs for key roles as command sergeants major and first sergeants.

The first wave of the new Sergeant Majors Assessment Program begins in November, Clark said, and it will evaluate potential brigade-level sergeants major to assess their readiness to lead at that level.

The program, which is modeled on similar command assessment initiatives already implemented for officers, will include cognitive and non-cognitive leadership assessments, written and verbal communication assessments, peer and subordinate feedback, and physical fitness. Potential CSMs also meet with a psychologist.

Approximately 380 sergeants major will compete for selection to 130 brigade-level positions, said Sgt. Maj. Robert Haynie, the Army Talent Management Task Force senior enlisted leader, in a June podcast.

Clark said a pilot version of the SMAP last year weeded out “a similar percentage” of NCOs as the battalion command assessment program did for officers.

The results of this fall’s expanded program will be used to develop and refine the final version of SMAP, according to the Army. And it will expand to include battalion-level CSM selection next year.

An assessment and selection program for first sergeants is in the pilot phase, too, Haynie said in the talent management podcast.

The First Sergeant Talent Alignment Assessment “is a decentralized assessment tool to be run at the division or installation level,” he said. “It’s about a four-day process, building out peer and subordinate feedback…and giving that to a talent alignment panel…then we do what’s called a behavioral-based interview.”

Haynie said the program will be able to identify the kind of enlisted leader a company needs and then use the attribute assessments from the first sergeant candidates in order to “match up the right NCO to the right position, based off of their knowledge, skills, behaviors and preferences.”

Thirteen master sergeants stationed at Fort Bragg participated in a pilot version of the program last year, and 15 NCOs from the 1st Infantry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, executed a test version of the assessment program, as well.

Army Times caught up with Haynie via phone during the program’s third pilot assessment with the 10th Mountain Division at Fort Drum, New York. He said there’s a fourth tentative pilot scheduled with U.S. Army Alaska before Grinston and other Army leaders will decide on the program’s future in October.

If senior leaders give the green light, the program will expand in fiscal year 2022 to include larger, division-led prototypes of the first sergeant talent alignment assessment before full implementation across the force in fiscal 2023, Haynie said.

Traditionally, first sergeant assignments have been managed internally by brigade command sergeants major. Haynie explained that by utilizing talent alignment principles and managing the process at the division or installation level, the talent pool for first sergeant positions will be greatly increased. Plus, deserving NCOs will have more leadership opportunities for which they’ll be considered.

Senior Army leaders strongly believe that identifying and better-managing talent will help reduce toxic leadership and reduce destructive behavior such as sexual harassment, sexual assault, and suicide.

“At the end of the day, the proof’s gonna be…[when] we start seeing a decline in the corrosive [behaviors],” said Command Sgt. Maj. Todd Sims, senior enlisted leader for Army Forces Command, on the talent management podcast. “That [will mean] we’ve got this exactly right. I look forward to it; I’m excited that we’re changing the process.”

Clark said that another byproduct of all the new merit-based programs and talent management initiatives has been a new outlook towards retention control points, which force NCOs out of the Army if they aren’t promoted by a certain point in service.

The reevaluation of RCPs is currently inspired by the brigade-level sergeant major assessment initiative, Clark said, but the Army is open to looking at changing policy for NCOs as junior as staff sergeants.

“We want to see if we are pushing talent out of the Army too fast,” he said, indicating that the Army will use data from the sergeant major program “to go back and look at how we will shape retention control point policy in the future.”

The Army-wide promotion OML evaluation boards could provide a basis for identifying non-performers for separation from the Army, Clark explained, similar to how the Army currently separates officers who are twice passed over for promotion.

All of these policies, Clark says, are ultimately intended “to set a culture that enables our ability to develop and employ [our] talent.”

Davis Winkie covers the Army for Military Times. He studied history at Vanderbilt and UNC-Chapel Hill, and served five years in the Army Guard. His investigations earned the Society of Professional Journalists' 2023 Sunshine Award and consecutive Military Reporters and Editors honors, among others. Davis was also a 2022 Livingston Awards finalist.