During my junior year at West Point in 2017, I attended a ceremony honoring the namesake of the school’s newest barracks: Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. This was the first building at West Point named after an African American, and I glowed with pride knowing that the academy was finally celebrating a person who looked like me.

It was a meaningful, but ultimately insufficient, gesture: Less than 100 meters from Benjamin O. Davis barracks was one named for Robert E. Lee, one of almost two dozen Confederate monuments on West Point’s campus at the time.

Walking to class every day, I passed the plaque for the Lee Award for Mathematics in Thayer Hall, complete with the inscription, “Donated by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.” After class, I often ran down Lee Road, through Lee Housing Complex, to Lee Gate. As I sat in the library on the weekends, a grand portrait of Lee in Confederate gray loomed over me, while a haunting depiction of a Black man in tattered clothes walked barefoot alongside Lee’s horse in the painting’s background.

The years I spent in the shadow of West Point’s Confederate monuments made me who I am today. My character development, the cornerstone of a West Point education, was forged by countless hours spent reading books, writing papers and sitting in lectures about moral courage and West Point’s guiding values of duty, honor and country.

But my understanding of actually living those values, being what we called “a leader of character,” was shaped in resistance to my alma mater’s Confederate idols and totems. I was not alone in my feelings of anger and dissatisfaction.

This collective feeling drove my friends and me to organize the “Hot Topics Forum” in 2017. At this event, likely for the first time since the Civil War, more than 200 members of the West Point community, including our commanding generals, gathered to discuss West Point’s memory of the Confederacy.

Speakers included those from both sides of the issue, including a white woman who shared how her Southern heritage shaped her understanding of and appreciation for Confederate monuments.

She was followed by a white cadet named Rob, also from the South, who grew up having few friendships with people of other races. During his freshman year, he hung a Confederate battle flag, which he considered a symbol of honor and tradition, in his barracks room.

He later spoke with other cadets, many of them Black, who explained how the flag was a distressing symbol of a dark and painful history. These conversations broadened his understanding of what the symbols meant, leading him to remove his Confederate flag and encourage the school to do the same with their Confederate symbols.

Following the forum, several people shared how hearing those personal stories changed their minds about Confederate monuments. I challenged some of West Point’s senior leaders: “Now that your mind is changed, what will you do about it?”

Each time, I was told that they would not take any action because West Point “couldn’t get ahead of the Army,” which still had nine bases named for Confederate soldiers.

After graduating from West Point and commissioning as a transportation officer, I was sent to one of those bases, Fort Lee, Virginia, to begin training as an Army logistician. The move to Virginia led me to discover parts of my family’s roots.

Every time I called my great-grandma Stith, she would say, “You know, you got lots of cousins down there in Virginia!” Her husband, Carroll Stith, was born in 1916 in Sussex County, part of Virginia’s “Black Belt.” The following year, just 30 miles north of my great-grandfather’s birthplace, Camp Lee opened.

Growing up with little knowledge of my family history, the South always felt distant. But when I learned about this historical intersection between my great-granddad’s childhood and the opening of Camp Lee, I thought back to a trip I’d made to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

There I gazed at dozens of steel coffins hanging overhead, each engraved with the names of a county where a lynching had occurred. I didn’t know it then, but above me hung the names of people lynched in the counties where my great-granddad was born and where I lived while serving at Fort Lee.

It is this legacy of racial violence that ties these two stories together. My great-grandfather and his brother fled north during the Great Migration, joining millions of refugees from the campaign of racial terrorism throughout the Postbellum South. As Black families were being driven from their homes, the U.S. Army decided to celebrate Robert E. Lee, the leader of a violent rebellion to maintain white supremacy and African slavery.

Like me, great-granddad Stith was an Army logistician. He was part of the extraordinary logistical effort during World War II to sustain a war on two fronts and on opposite sides of the globe, executed in large part by units of Black soldiers.

He deployed to the Pacific with a segregated unit to build airfields and roads, joining not only the Black truck drivers on the famous Red Ball Express, but also Black soldiers serving as engineers, quartermasters, construction workers and supply troops that sustained the U.S. military around the world.

I never heard the stories of Black World War II veterans until I searched for stories about my great-granddad. Looking for those stories brought me to discover the soldiers from the 320th Balloon Barrage Battalion, who were among the first to land at Omaha Beach on D-Day.

As much as I was inspired by the heroism of Black soldiers like Waverly Woodson Jr., I was angry that their stories and so many other were not included in movies like “Saving Private Ryan,” in hundreds of pages of Stephen Ambrose books and many more of the war’s most famous retellings.

By leaving out the contributions of women and people of color, storytellers sidestep the contradictions and complications their presence brings to this American story. But it was these contradictions that I found most compelling because I saw my own experiences in them.

The Black GIs fought what they called the Double Victory Campaign, seeking to defeat fascism abroad and racism at home. Many of their stories took me back to Virginia.

The bases where I served were where many segregated units trained before deploying to Europe and the Pacific. Before landing on the beaches of Normandy, some of the soldiers who later joined the 320th Balloon Barrage Battalion trained at Fort Eustis, Virginia, where I served for almost three years as a lieutenant. I can still remember feeling chills run through my body as I read the words of a soldier from New York: “I never knew what discrimination was until I went to Fort Eustis.” At the same time, Black soldiers training at then-Camp Lee recalled being slapped, threatened and called racial slurs daily.

One of the Black soldiers during that period was Arthur Gregg. When Gregg served as a second lieutenant at Fort Lee in 1950, he was banned from the segregated officers’ club.

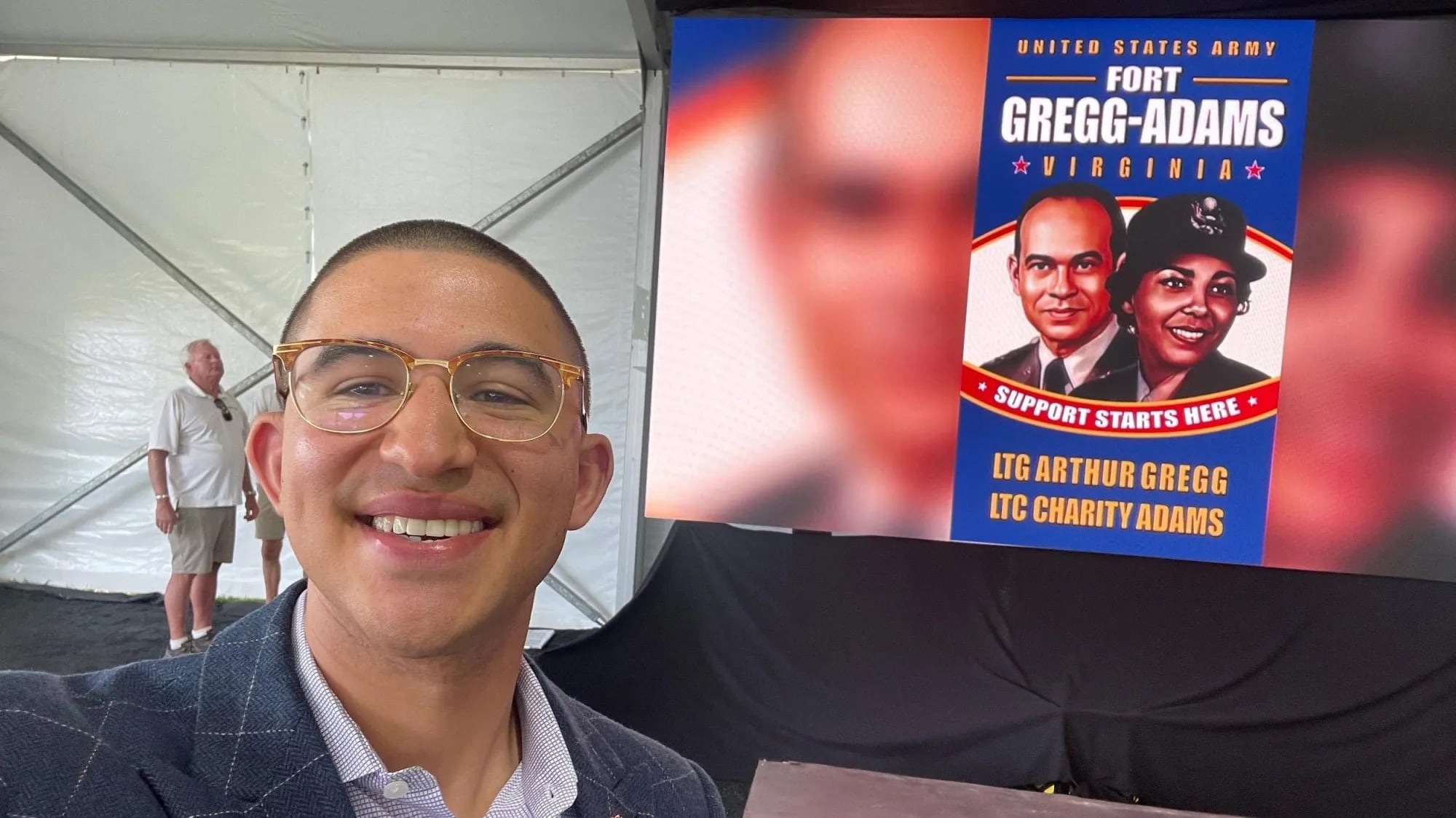

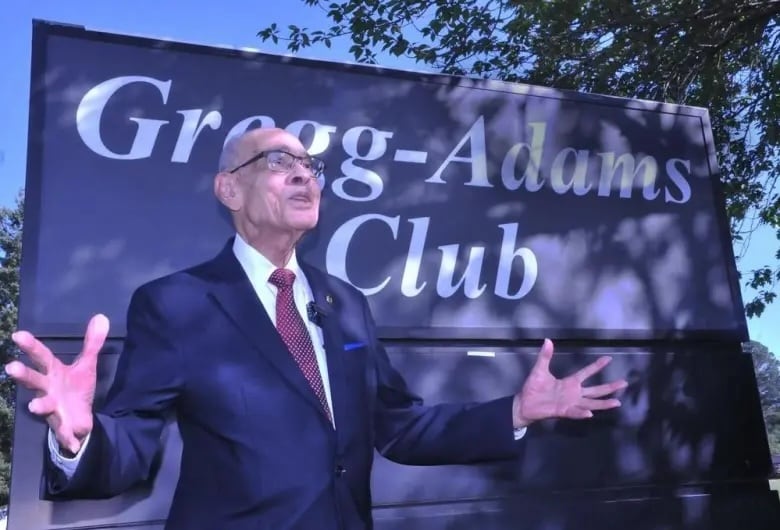

In 2023, I watched from the audience as then-94-year-old retired Lt. Gen. Gregg walked to the podium on the day Fort Lee was redesignated to Fort Gregg-Adams, part of a congressional effort to bar military installations from honoring Confederate leaders. He stood in front of that very same officers’ club and watched as his name was hung in front of the door.

The ceremony carried the unmistakable mood of a family reunion. Dozens of Black women, descendants of the women who served in the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion with Lt. Col. Charity Adams, were in attendance, showing off their matching white T-shirts with Gregg and Adams’ faces printed on the front, and the words “From Lee … To Gregg-Adams” written on the back.

I was so excited that the place where my soldiers would learn our craft would be named after people we could be proud of. And more than that, people who would finally represent the diversity of the men and women who served there, past and present.

As I drove through the gate that day and saw banners with Gregg and Adams’ faces prominently displayed on every light pole, I felt a weight lift. I no longer had to carry the resentment toward the fact that the same symbols that intimidated my great-grandfather and his community were still standing as a barrier to inclusion for me and other soldiers.

After twice serving at the base near Petersburg, once while it was named Fort Lee and again after it was redesignated as Fort Gregg-Adams, I took command of a company of Army logisticians. Today, people of color make up the majority of the logistics branches; Black service members represent exactly 50%. In the transportation company I command, almost half my soldiers are Black and more than a quarter are Latino.

Every single one of them starts their Army career at the Sustainment Center of Excellence, which, after the 2025 decision to restore former base names, is located at a place once again called Fort Lee.

When I first learned about the reversion to Confederate base names, my bewildered frustration quickly led towards despair. So many of my assumptions about the world and how to better it were turned upside down. There was a good faith assumption behind Hot Topics. We believed that if we could connect with people, we could change their minds, and through that, change policy.

The decision to remove Confederate names was proof that our stories were finally heard. And because of this, the reversal to Confederate names felt like open mockery.

Compounding the hurt, some of the people around me eagerly embraced the change. They laughed as it was all torn down. In a meeting with fellow commissioned and noncommissioned officers in my battalion, a chorus of smiling white men shouted almost in unison, “It’s called Fort Bragg now!” at their first chance to start using Confederate names again. I waited for someone around me to express the same outrage and betrayal I was feeling. But it never came.

One afternoon, I got a call from my granddad. When I answered, he skipped the pleasantries and asked, “How can you keep putting up with this?” I could sense the anger and concern in his voice. He then moved directly to Confederate base names, saying, “They are dismantling everything that people like you and your friends fought to correct.”

That comment knocked the wind out of me. Normally, my grandparents overflow with pride when they talk about the Army. My grandma wears my West Point necklace religiously, as my granddad does with his West Point baseball cap. They jump at any chance to talk about their West Point grandson, even introducing me to their neighbors as “Capt. Jack Lowe.”

But even all the love of a proud grandparent could not stop them from being filled with shame and disappointment in the Army I now represent. Even as I continue to put on the uniform, I share many of my grandparents’ feelings.

But from the stories of Black soldiers who came before me, I learned that I’m not the first to feel this way, and unfortunately, I won’t be the last. The Double Victory Campaign continues.

Jack Lowe is a captain in the U.S. Army Logistics Branch with years of experience serving in transportation companies, including during a deployment to Poland in support of Operation Atlantic Resolve. He graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 2019 and earned a degree in sociology. He is the first Black cadet to be awarded the Fulbright scholarship and earned a master’s degree in cultural criminology at Lund University in Sweden. His academic work, published in the Nordic Journal of Criminology, analyzes how narratives about crime and immigration shape the boundaries of acceptable punishment and national identity.

The author is writing this essay in his personal capacity, with no association to any official military position. The views expressed are those of the individual only and not those of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

This War Horse Reflection was edited by Kim Vo, fact-checked by Jess Rohan and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.